In the midst of the Russian Revolution, as the Bolsheviks and their enemies battled for control of the sprawling, crumbling empire, a small but internationally-minded group of artists were also conspiring against one of the seemingly unmovable forces of centuries past. Their target was not the monarchy or the systematic oppression of the peasant and worker classes (at least not directly), but the entire system of realist, figurative aesthetics. It was a wholly new time, they felt, and they needed a new artistic sensibility to match. The result was the revolutionary work of the Russian avant-garde and its two greatest movements: Suprematism and Constructivism.

Though closely related and, the factions were in fact diametrically opposed; Suprematism, named for what its founder Kasimir Malevich called “the supremacy of pure artistic feeling,” looked to color and geometric forms as a way of distilling art to its essential parts. Constructivism, on the other hand, saw art as a site for functional, socially-conscious endeavors rather than individualistic expression—adherents like Alexander Rodchecko and Vladimir Tatlin made propaganda posters and designs for public buildings in addition to paintings and sculptures.

Though both movements fell out of favor with the Soviet government following the rise of Stalin and his preferred Socialist Realist style, the work from this period extended far beyond the avant-garde enclaves of Russia into the visual idiom of the Bauhaus, De Stijl, and even contemporary graphic design. These six examples, excerpted in their entirety from Phaidon’s The Art Book, are among the most important and iconic of this heady era.

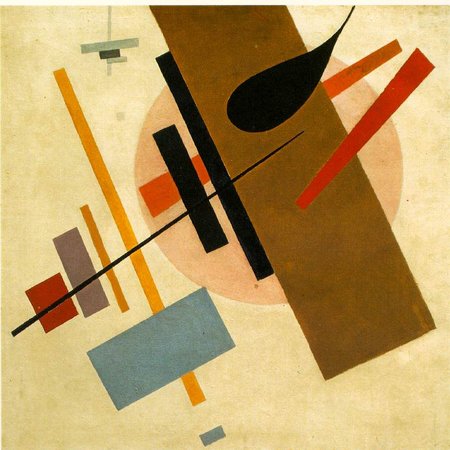

KASIMIR MALEVICH

Suprematism, 1915

Geometric elements painted in basic colors appear to float as if suspended on the canvas. Malevich has created a complex composition by overlapping the forms to convey a sense of perspective and depth. A Suprematist work, it banishes every trace of subject, relying solely on the interaction between form and color. Malevich was the founder of Suprematism, a system which strove to achieve absolute purity of form and color. For him, this method constituted an expression of pure artistic feeling, or what he called “non-objective sensation.” In 1918, he took the development of non-objective art to its logical conclusion in a series of works entitled “White on White,” consisting of a white square on a white background, the abstract to end all abstracts. Realizing at this point that he could take the concept no further, he reverted to figurative paintings.

ALEXANDER RODCHENKO

Composition (Overcoming Red), 1918

Triangular shapes balanced in front of circles create a three-dimensional illusion, which is enhanced by the dark shading on the left diagonals of the triangles. The flat forms are divided by color and appear to rotate. Composed of strictly geometric designs traced with a compass and ruler, the painting reflects the artist’s search to create elementary shapes in pure, primary colors. In the same year as this painting Rodchenko exhibited his famous Black on Black painting, a response to Kasimir Malevich’s “White on White” series. Rodchenko’s desire to reduce painting to its abstract, geometric essentials led to his incorporation into the Constructivist movement. In common with other members of this group he later gave up easel painting in favor of design and the applied arts. He was particularly active in industrial design, typography, and photography, the latter often exploiting unusual perspectives and angles of vision.

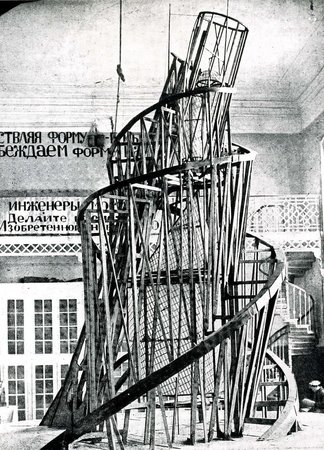

VLADIMIR TATLIN

Monument to the Third International, 1919

Created in a moment of political enthusiasm, this leaning spiral was designed to be twice the height of the Empire State Building in New York and to have alternately rotating central sections. Space is ordered into fragmented compartments that are formally related to each other as in a mathematic equation. Tatlin was the founder of Constructivism, a Russian art movement that grew out of artistic experiments with abstraction but later turned to more utilitarian concerns. He advocated the idea of the “artist engineer” and saw the primary role of Constructivism as fulfilling social needs. Tatlin also created a series of hanging relief constructions using a variety of materials such as wood, metal, glass and wire and employing exclusively geometric forms. This masterpiece, a symbol of Constructivist ideals combining the disciplines of sculpture and architecture, was never constructed. The piece illustrated is a modern replica of the original model.

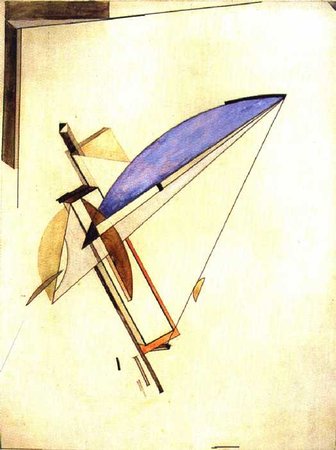

EL LISSITZKY

Composition, c. 1920

Revolving geometric objects painted in delicate colours appear to be floating in the air, thus creating a sense of depth and an illusion of space. Some of the shapes are given three dimensions, and this suggestion of architectural forms was developed in Lissitzky’s later works. In its concentration of pure form and colour, the drawing shows the influence of Suprematism, an abstract art form invented by Kasimir Malevich based on pure geometric figures. Lissitzky trained first as an engineer, then as an architect. Marc Chagall appointed him professor of architecture and graphic art at the art school in Vitebsk, where he came under the influence of Malevich. His series of “Prouns” is well-known – a number of abstract works of straight lines, dramatic architectural qualities and an overall flatness, with no suggestion of depth. Lissitzky’s creative versatility extended to designs for costumes, exhibitions, posters and books.

LJUBOV POPOVA

Space-Force Construction, c. 1920–1

Overlapping geometric shapes, painted in muted colors, appear to be floating on the unpainted plywood background. The interplay of these various circles, curves and diagonal lines is enhanced by multicolored shadows which contribute to the effective play of light. A further sense of depth is created by the diagonal lines, which appear to extend beyond the picture. In its emphasis on color and form and the use of added shadow to increase perspective, the painting demonstrates the influence of Constructivism. From 1921 Popova turned her talents towards textile, costume and set design. In tune with the spirit of Constructivism, she believed that art should serve a useful purpose, claiming that “no artistic success has given me such satisfaction as the sight of a peasant or a worker buying a length of material designed by me.” One of the most important members of the Russian avant-garde, she died prematurely of scarlet fever, at the height of her career.

NAUM GABO

Linear Construction in Space No. 2., 1957–8

A nylon string is wound around two intersecting sheets of curved perspex to create a complex three-dimensional pattern of concave and convex folds. It was conceived as part of an unrealized 3-metre (15-foot) commission for the Esso building in New York in 1949. With this extraordinarily ethereal sculpture Gabo has achieved an example of delicacy, transparency, and weightlessness that was unprecedented. The sculpture seems to float as if suspended from an invisible cord and, having no beginning or end, it conveys a sense of infinity. Gabo was a Constructivist and this work is an example of the movement in the way that it captures the indefinite expansion of space. Gabo left his native Russia in 1922, and spent time in Berlin and Paris before becoming an American citizen. In 1952, he combined his artistic talents with architecture, constructing an enormous monument for a department store in Rotterdam.