To claim the prolific Hungarian-born Modernist, architect, and designer Marcel Breuer has made a lasting impact on art and architecture is, quite simply, an understatement. With internationally recognized institutions like the Met Breuer echoing his name and all manner of contemporary furniture designs borrowing from his iconic formal language, Breuer has firmly claimed his place in 20th century art history.

But before the fame and glory, Breuer was but a teen artist navigating the murky waters of art, craft, and industry. In this excerpt from Robert McCarter’s essay in Phaidon’s new and comprehensive monographBreuer, we take a deeper look at Breuer's beginnings as a Bauhaus student in the heady days of the 1920s—a period that not only informed the figure Breuer was to become, but was also undeniably shaped by the ambitious young man himself.

Marcel Lajos Breuer (called Lajkó by all who knew him) was born on 22 May 1902 in the Hungarian town of Pécs, at that time a regional center with a population of 42,000, located near the west banks of the Danube River in the western portion of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. With its mining, industry, and the oldest university in Hungary, the city of Pécs was the most important economic and cultural center in western Hungary during the eighteen years that Breuer lived there. In 1919, at the end of World War I, Pécs became one of five primary provincial centers of the newly established Hungarian Republic, and the Hungarian border with Yugoslavia was located just to the south of Pécs, which is 100 miles (160 km) to the south of Budapest, and almost the same distance to the east of Zagreb, Croatia, and to the northwest of Belgrade, Serbia.

Breuer’s father was a dental technician, allowing the family to live comfortably and to engage in the progressive, intellectual culture of Pécs. Breuer grew up speaking Hungarian, as well as some German, and while his parents were Jewish, Breuer later decided, at age twenty-four, to renounce all religion. Breuer’s father and mother were interested in having their three children engage in the arts and culture, and they subscribed to several art periodicals, including The Studio, an English publication presenting recent international developments in fine arts, applied arts, and architecture, which was widely read throughout Europe and the United States.

Steeped in this context, Breuer decided as a youth that he would become an artist—either a painter or a sculptor. At home, he painted, sketched, and modeled, and at secondary school he enjoyed mechanical drawing. An oil painting by Breuer, depicting the roofscapes of Pécs and the surrounding hillsides, remains from 1917. At the end of World War I, from 1918 to 1920, Breuer remembers Pécs being occupied by the Serbs and Yugoslavs, stating that he and his family felt “completely isolated. Consequently I had no knowledge of modern art.” However, due to his early and ongoing exposure to international journals such as The Studio, Breuer could not have been entirely unaware of the dramatic changes happening in the arts and architecture at that time.

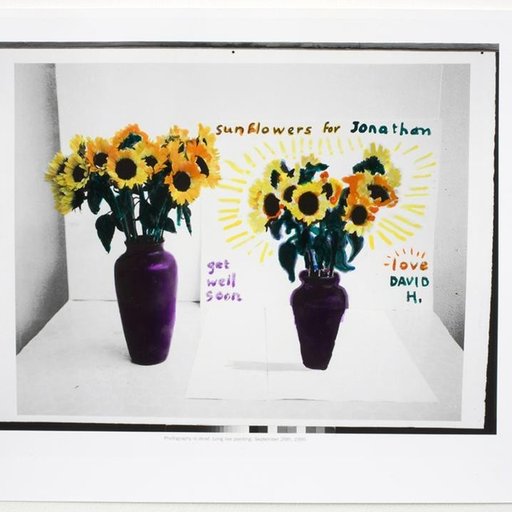

Dressing table and chair, Haus am Horn, 1923

Dressing table and chair, Haus am Horn, 1923

In spring 1920, at the age of eighteen, Breuer received a scholarship to attend the Akademie der bildenden Künste (Academy of Fine Arts) in Vienna, one of the greatest cultural centers of the world. In the years before World War I, Vienna had been the context for many of the most profound developments in early modernism. Before the turn of the century, the painter Gustav Klimt had broken away from the classical Imperial Academy and established the “Secession,” which soon included a number of architects such as Joseph Maria Olbrich and Josef Hoffmann.

The Secessionist school of architecture, as well as its critics, were both inspired by the work of Otto Wagner, architect of many of the Vienna city transit stations and bridges, as well as masterpieces of early modern architecture such as the Post Office Savings Bank and the Am Steinhof Church. Hoffmann’s establishment of the Wiener Werkstätte, and the relation of many of the Secessionist architects’ works to Art Nouveau, along with their employment of newly invented ornament, was severely criticized by the architect Adolf Loos and the cultural critic Karl Kraus, whose scathing denunciations of what they saw as cultural degeneracy appeared in issues of Loos’s journal, Das Andere (The Other).

Loos’s own architecture, which had restrained exteriors with complexly interlocking interior spaces, was closely related to the Arts and Crafts movement, as documented in The Studio. Among parallel cultural developments in Vienna before World War I, there was Arnold Schönberg in music, Sigmund Freud in psychology, Robert Musil in literature, Ernst Mach in science, and Ludwig Wittgenstein in philosophy, to name only the most well known.

Despite his high expectations, Breuer was deeply disappointed when he arrived at the Academy of Fine Arts, finding the students uninterested and the teachers uninspiring, everyone being occupied with discussions of aesthetic theory and not with the actual making of art. He walked out of the Academy the same day, abandoning his scholarship and seeking out a position as a designer with an architect and cabinetmaker in Vienna, where he stayed for two months.

As Breuer recalled, there were many Hungarians in Vienna in 1920, including a number of exiles from the failed Hungarian Communist revolution of the year before. During his brief time in Vienna, Breuer “studied with great interest art journals in the cafés,” and he recalls experiencing firsthand some of the city’s important modern buildings. However, he would later characterize these two months as the unhappiest time of his life, almost despairing until one day his friend from Pécs, Fred Forbàt, a recent architecture school graduate, gave Breuer “a little brochure from the Weimar Bauhaus with the emblem 'Return of the Craftsman' and with a woodcut by Lyonel Feininger.” Knowing nothing more about this new school than what was written in the four-page brochure, Breuer decided to go to Weimar and enroll in the Bauhaus.

When Breuer, then age nineteen, arrived in Weimar to join the Bauhaus, the school was only a year old, having been founded the previous year by Walter Gropius, the architect of the Fagus Factory (1911) and the administration building of the Deutscher Werkbund exhibit of 1914, both of which have been recognized as early landmarks of modernism. The Werkbund had been founded to develop close relationships between art and industry in Germany, and one of its founders, the Belgian architect Henry van de Velde, had stepped down as director of the Grand Ducal School of Arts and Crafts in 1915, and subsequently urged that Gropius be appointed to replace him.

In 1919, Gropius established the Staatliches Bauhaus Weimar as a combination of the Academy of Art and the School of Arts and Crafts, “in conjunction with a newly affiliated department of architecture,” as declared in the four-page brochure Breuer was given. More than anything else, it was Gropius’s “emblematic” vision for the school as a place where the artist and craftsman were one and the same, as stated in the 1919 brochure, that had drawn Breuer and other students to Weimar:

The ultimate aim of all visual arts is the complete building! … Today the arts exist in isolation, from which they can be rescued only through the conscious, cooperative effort of all craftsmen… Architects, sculptors, painters, we all must return to the crafts! For art is not a “profession.” There is no essential difference between the artist and the craftsman. The artist is an exalted craftsman … But proficiency in a craft is essential to every artist. Therein lies the prime source of creative imagination. Let us then create a new guild of craftsmen …

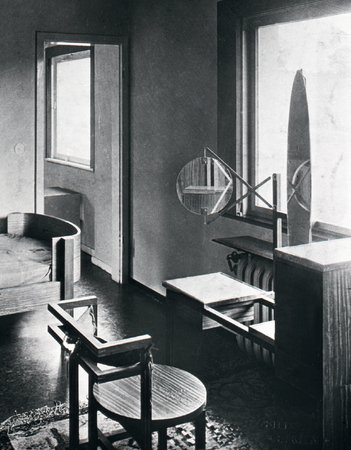

Thost Apartment, Hamburg, 1926

Thost Apartment, Hamburg, 1926

Yet Gropius’s definition of the school as including architectural education, stated in the 1919 brochure, would not become a reality until 1927. In addition, his medieval, guild-based conception of education, moving from apprenticeship to journeyman to “young master,” and involving the engagement of art with industry, was being engaged only partially by the Bauhaus faculty Breuer found when he arrived at the school. Besides Gropius, the faculty then included the painter Lyonel Feininger, the ceramicist Gerhard Marcks, and the painter Johannes Itten.

As if the diversity of viewpoints represented by the rapidly growing Bauhaus faculty was not enough, Theo van Doesburg, the founder of the Dutch De Stijl movement, had also arrived in Weimar that same year with the express purpose of setting up a competing “school,” giving lectures every evening to the Bauhaus students, who attended in large numbers. The sculptor Oskar Schlemmer, who joined the Bauhaus faculty at this time, wrote how van Doesburg was “drawing the Bauhaus students under his spell—especially those interested chiefly in architecture, who deplore the Bauhaus’s deficiency in this area … He rejects craftsmanship (the focus of the Bauhaus) in favor of the most modern tool: the machine. [He argues for] exclusive and consistent use of only the horizontal and the vertical in art and architecture . . .”

The summer of 1920, when Breuer arrived, coincided with the first time Bauhaus students were taught the Preliminary Course, or “Vorkurs,” involving six months of instruction imparting the fundamentals and principles of form, material, and design process, later known as “basic design.” One of the most important contributions to art and architecture education to emerge from the Bauhaus, the Preliminary Course was initially taught by Itten, who encouraged individual intuitive development (including allowing students to propose their own color palettes), while also engaging the spiritual.

Itten’s personal beliefs about the fundamentally mystical and subjective nature of artistic creation led him to oppose the close relationship of art education and industrial production that Gropius advocated. Later that autumn, the painter Paul Klee was asked to join the faculty of the Bauhaus as a Master, and he described attending Itten’s Preliminary Course class, giving a detailed account of the students’ typical experiences in the early Bauhaus, in a letter to his wife Lily in January 1921:

Yesterday I devoted myself entirely to the Bauhaus and had myself shown over the place for the first time. In the morning Itten was working with the Preliminary Course class … Wearing a wine-red suit, the Master was standing with a group of girls and boys and asking them to show him work. He gave one group a writing exercise based on the text “Little Mary Sat on a Stone.” They were only allowed to begin writing when they clearly felt the spirit of the song …

We went into the studio next door, a vast room. Along one wall were supports holding experiments in the use of materials. They looked like the bastardized offspring of couplings between the art of savages and children’s toys. Along the other three walls were tables at which the apprentices sat on three-legged piano stools … Everyone had a huge piece of charcoal in his hand and a pad of cheap paper on a drawing board in front of him … After he’d walked up and down once or twice he moved toward an easel and a pad of paper. He grasped a stick of charcoal, gathered his body together as though charging himself with energy and then suddenly made two movements, one after the other. We saw a shape formed by two energetic strokes, vertical and parallel, on the topmost sheet of paper. The students were instructed to copy it. The Master criticized the work, had one student demonstrate, controlling the attitude of his body. Then he demanded that it be done while beating time; then he had the same exercise performed with everyone standing.

It seems that what’s intended is a kind of body massage in order to train the machine to function with feeling. Similarly new elementary forms … were created and copied … with several explanations about why and about the kind of expression. Then he said something about the wind, had some of the students stand up and express the feelings inspired by the wind and storm. Afterward he gave the exercise: the representation of the storm. For that he allowed about ten minutes and then inspected the results. With that he criticized. After the criticism work resumed. One sheet of paper after another was torn up and fell to the ground. Several worked with great energy so that several sheets of paper were used up at the same time. After they had all grown rather tired he let the members of the Preliminary Course take the exercise home with them for further practice.

In the evening at five o’clock “Analysis” was held in a large room built like an amphitheatre … Once again the Master walked up and down by way of preparation and charging his batteries. Then he presented the formal elements that he wished to discuss in the picture by Matisse, La Danse, which was later projected [on the screen at the front of the room]. He then had the students draw the compositional scheme of this picture, once even in the dark. Then he had them add to this scheme after the model, sometimes telling them to copy a single figure. Again and again he walked up and down the steps of the room, inspecting, criticizing.

Klee’s description is paralleled by Breuer’s later recollections that Itten’s class involved “doing rhythmic movements, designing in rhyme, reinterpreting the Old Masters of art, studying the textures of materials, and expressing our different feelings in a direct manner.” While Itten would leave the Bauhaus in 1923, before Breuer had completed his studies, his influence would remain in the teaching of the Preliminary Course, the one common class in which all Bauhaus students were required to enroll.

After Itten’s departure, the Hungarian Constructivist painter, photographer, and graphic designer László Moholy-Nagy took over the teaching of the Preliminary Course. Josef Albers, another student who entered the Bauhaus at the same time as Breuer, would later join what was by that time a team of teachers for the Preliminary Course. Albers’s teaching at the Bauhaus, at Black Mountain College, and at Yale University, which included the training of the body to draw with feeling (inspired in many ways by Itten’s teaching of the Preliminary Course), would have the most profoundly formative effect on generations of artists and architects.

Klee’s class notes from the period when Breuer was a new student at the Bauhaus, wherein Klee endeavored to teach students “how to see” and how to shape movement through space, are documented in The Thinking Eye and The Nature of Nature, which are among the most important books on modern design education. Breuer considered Klee to be one of the two most influential teachers he ever had, and he recalled how, during a lecture at the blackboard, Klee “drew an arrow pointing to the right, wrote over it 'Movement,' then another one pointing toward the left with the caption 'Counter Movement.' It took the audience some time to discover that with the second arrow he changed the crayon into his left hand and wrote 'Counter Movement' from right to left.”

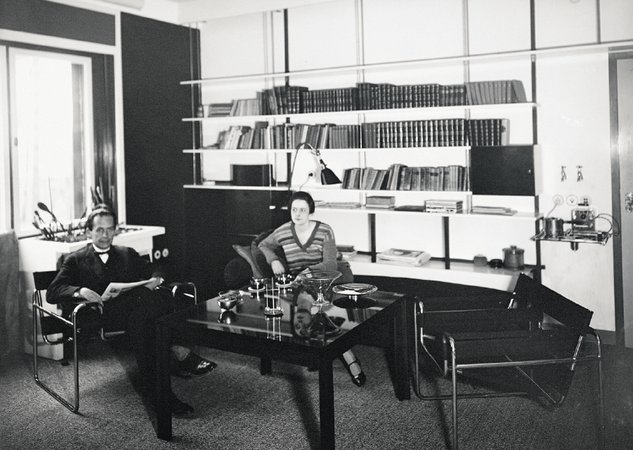

Ise and Walter Gropius in their Bauhaus apartment, 1927; with B3 Wassily chairs

Ise and Walter Gropius in their Bauhaus apartment, 1927; with B3 Wassily chairs

Breuer, Albers, and the other 141 students who enrolled with them in the 1920–1 academic year, entered the Bauhaus at a time when the faculty, the program of study, and the workshop facilities were all largely undefined, undeveloped, and in a state of flux; Gropius referred to the autumn of 1920, Breuer’s first semester, as a “chaotic” time at the Bauhaus. Albers, who could not afford the expensive drawing and painting supplies required for his courses, resorted to scavenging for materials at the city dump, from which he constructed a series of glass and wire compositions that were highly praised by the faculty, leading to Albers being asked to organize a new glass workshop for the school. Albers’s and Breuer’s fellow student, Gunta Stölzl, who had entered the Bauhaus the year before, would go on to become the director of the weaving workshop. Breuer himself would return in 1925 as director of the carpentry workshop.

After completing the Preliminary Course, the Bauhaus students selected one of several workshops, each headed by a Master of Form and a Master of Craft. While Gropius intended that there would eventually be Bauhaus workshops for a variety of materials—wood, stone, metal, clay (ceramics), glass, color (wall painting), and textiles—when Breuer arrived, in 1920, the only fully operational workshops were those in weaving and bookbinding. In 1921, following on his original desire to become skilled in a craft, and to learn how to make things, Breuer chose to enter the wood or carpentry workshop, which was then directed by Form Master Itten and Craft Master Joseph Zachmann.

From the moment he first arrived at the Bauhaus, Breuer was recognized as an exceptionally talented student. He soon became close friends with Gropius and his wife, Ise, and this relationship would profoundly shape Breuer’s professional life for the next twenty years. Gropius, who was nineteen years older than Breuer, immediately recognized the young man’s remarkable skills in the aesthetic and functional making of material form. As a result, Breuer “participated in, and contributed to, the many crucial changes that occurred during the early years of the school. And his work, perhaps more than that of any other student, reflected the change in philosophy of the Bauhaus from the primarily craft orientation with which it began, to the principles of the merging of art and industry for which it subsequently became famous.”