Glenn Ligon is having a big February—the American conceptual artist has not one but two exhibitions, in Luhring Augustine’s two New York locations. In addition to “We Need to Wake Up Cause That's What Time It Is,” the already-acclaimed show of Ligon's work in the gallery’s Bushwick location, Luhring Augustine's Chelsea space will also host both “What We Said Last Time” (a series of prints based on James Baldwin’s 1953 essay “Stranger in the Village”) and “Entanglements,” a curatorial project by the artist featuring pieces by On Kawara, Andy Warhol, and others (opening February 27).

To get you prepared for the coming flood of Ligon-love, here’s an essay by the Hammer Museum's Chief Curator Connie Butler—excerpted from from Phaidon'sDefining Contemporary Art—on the artist's seminal 1991 work Untitled (“I am an invisible man”), one of the earliest examples of his ongoing engagement with text as a consciousness-raising medium.

Glenn Ligon’s work is about creating identities—those we build for ourselves and those determined for us by others. Ligon is part of a generation of artists who came to prominence in the 1990s for work that addressed the personal through emotionally heated subjects like racism and sexism. Because he is African-American, his work is often discussed solely in terms of race. "There was an assumption that artists of color could only and would only talk about their identity," he has said. "From the beginning, myself and a whole group of artists [...] resisted the notion that there was some easily identifiable, unified, readily agreed-upon thing called blackness that we could present in our work."

Although the complex history of race in America is certainly a continual theme for Ligon, the diversity of media and techniques he has employed over the course of his career to create a compelling body of work is mirrored by the breadth of the topics he has tackled—the efficacy of language and the visual image in communications, the problem of authorial presence in a work of art, the role of social versus personal forces in shaping a message. His work forces a critique by its viewer, even if he, as the artist, refuses to take a side. Notes in the Margin of the Black Book (1991-93) juxtaposes the erotic photographs of black male nudes from Robert Mapplethorpe’s 1986 publication Black Book with framed texts taken from a range of sources, some specifically addressing the images at hand, some not. This compilation of provocative images and opinions is presented for our consideration and thoughts on the construction of the black male identity.

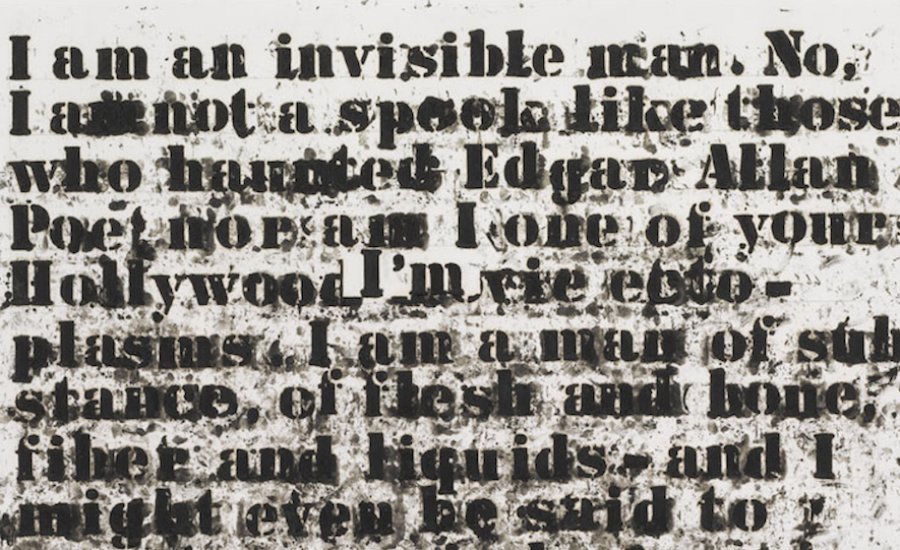

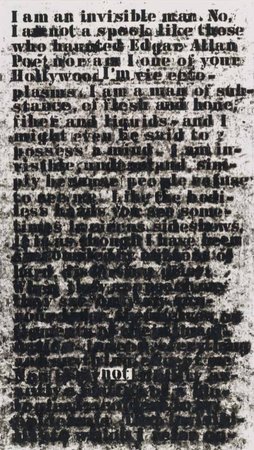

Glenn Ligon's Untitled (“I am an invisible man”), 1991

Glenn Ligon's Untitled (“I am an invisible man”), 1991

Ligon’s most resolved and effective works are his text-based drawings and paintings of the 1990s. In this iconic body of work, the artist selects fragments of text—from works of literature by authors such as James Baldwin, Zora Neale Hurston, and Walt Whitman, or from other sources, including a New York Times article about the defendants in the 1989 Central Park Jogger case—and stencils them onto sheets of paper or canvas. Using black oil stick to trace the words, Ligon’s technique ranges from exacting to deliberately overworked, and the results affect the legibility of the text.

While letters at the top of the composition may be clearly outlined, thicker and smudgier layers of paint further down obscure the words beyond recognition; we are aware that the information is there, but we can’t access it. In later works, Ligon began adding coal dust, which would stick to areas of wet lettering, further complicating any attempts to read the text but adding a luscious textural element, clearly positioning them as visually seductive works of art as well as fragments of writing. The conflict between the efficacy of these two forms of communication is often at the heart of these works. "Text demands to be read," says Ligon, "and perhaps the withdrawal of the text, the frustration of the ability to decipher it, reflects a certain pessimism on my part about the ability and the desire to communicate."

With this in mind, Ligon’s Untitled(“I am an invisible man”), with its excerpt from the famous first lines of Ralph Ellison’s 1952 novel Invisible Man, is a brilliant inversion of the expected relation between text and image. As the author elaborates on the premise that his character (or is it Ligon himself?) is invisible, the text becomes increasingly illegible, while the visual draw of the work as a visual art object grows with the layers of thick oil stick. A separate, floating statement—"I’m not"—is superimposed on the longer text but has a reverse relationship to the composition; the first word gets lost somewhat at top, while the emphatic denial is very clear at bottom. The work is about a kind of cultural blindness, literally enacted by the viewer. Reading is obfuscated even as identity is constructed.