Although technologies and fashions may evolve with dizzying speed, the human body is supposed to remain more or less constant. In the tumult of the 20th century, however, the human figure became the site of immense change as artists struggled to represent our fragile bodies in a time of unprecedented advancements and horrors. These seven paintings from the past century, excerpted from Phaidon'sThe Art Book, 30,000 Years of Art, and Body of Art, show just a few of the ways artists reimagined the human figure.

RELATED ARTICLES:

Brancusi to Bourgeois: The Evolution of the Human Figure in 7 Twentieth-Century Sculptures

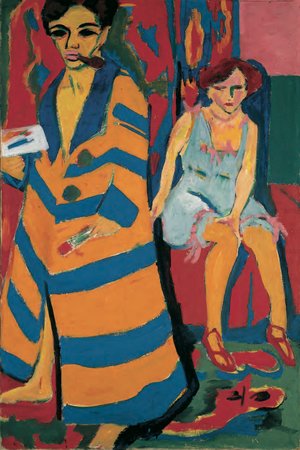

SELF-PORTRAIT WITH MODEL

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner

1910

Four architecture students – Fritz Bleyl, Erich Heckel, Karl Schmidt- Rotluff and Ernst Kirchner (1880– 1938) – formed the German Expressionist group Die Brücke (‘The Bridge’) in Dresden in 1905 with the goal of creating a "bridge" to a better, more perfect future. The group rejected the then current styles of academicism, realism and Impressionism. Instead, they looked to such Post-Impressionists as Vincent van Gogh and Paul Gauguin, the German Middle Ages and the Renaissance, primitive art and Art Nouveau, with the aim of creating a new, expressionistic art. Kirchner’s work contains echoes of the agitated state of Europe on the brink of World War I. His figures are often tense and distorted, as if to convey disquieting moods. In Self-portrait with Model, the artist depicts himself confronting the viewer with his female sitter posed to the right, in livid colours and reduced, angular forms that disrupt ordinary perspective, filling the composition with their smouldering intensity. This approach is typical of Expressionism, in which raw, subjective feelings seem to overwhelm objective observation. The mask-like faces heighten the psychological drama. Kirchner had been traumatized by World War I, and the rise of Nazism and increasing ill health exacerbated his insecurity until, in 1938, he committed suicide.

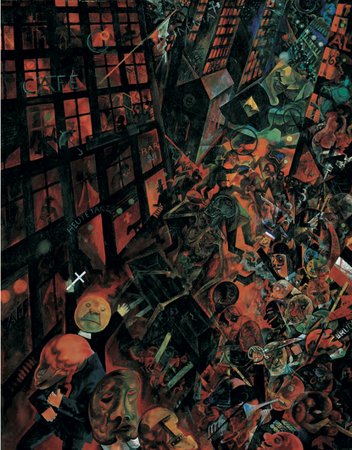

DEDICATION TO OSKAR PANIZZA

George Grosz

1917-1918

Following six months of military service in 1914, George Grosz (1893–1959) was conscripted again in 1917 and finally discharged after a bout of violence and a stay in a mental hospital. His early drawings and paintings were apolitical, but after his war experience his work changed fundamentally: the German army, along with politics in general, the aristocracy, commerce and religion, became the targets of his virulently satirical art. He became a misanthrope and a Utopian and came to hate Germans, particularly Berliners; he anglicized his name, hoping to use his stridently moral art to become the German Hogarth. Dedication to Oskar Panizza (1917–1918) depicts Grosz’s distopian vision of a hell-like, post-war metropolis (Panizza was a disgraced German writer who was extremely critical of society). A moon-faced priest marches at the head of a chaotic procession, followed by Death, who sits atop a coffin drinking schnapps from a bottle. The sharp perspective of the road makes the jumbled angles of the skyscrapers all the more precarious; the bloodthirsty and anarchic crowd seems oblivious to the towers that are about to tumble down. Grosz joined the Berlin Dada movement in 1918, embracing its anti-war, anti-bourgeois, anti-aesthetic protest even after returning to a more realistic style of painting in the 1920s. His modernist caricatures, overt criticism of German society and rejection of Nazism forced his emigration to the United States in 1933.

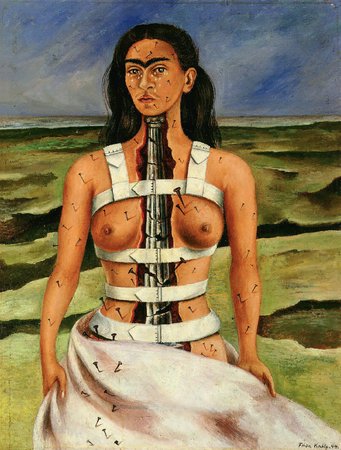

THE BROKEN COLUMN

Frida Kahlo

1944

Frida Kahlo (1907–54) began painting at 18, simply to pass the time in the hospital while she recovered from a bus accident; both art and the trauma of her accident would stay with her permanently. Over the remaining 29 years of her life, her injuries required 32 operations, which were frequently the subject of her approximately 200 self-portraits. Kahlo’s work has often been associated with Surrealism because of its seemingly fantastic imagery; in fact, the movement’s founder, André Breton, wrote an essay to accompany her 1938 solo exhibition. However, Kahlo asserted she was not interested in dreams or the unconscious, as the Surrealists were, but in her own reality. In The Broken Column, Kahlo stands tall, supported by the steel orthopedic corset that she wore in real life, and stares out at the viewer as tears run down her cheeks. Torn open, her throat and torso reveal an ancient fluted column, its strength and elegance now in ruins. Pierced with nails, Kahlo suffers Christ’s martyrdom, but unlike the singular Crucifixion, she endures her pain day after day, year after year – hence the countless nails in her flesh. The desolate background, empty and torn, embodies her pain; her suffering is not only physical, but permeates her whole world.

THE JUNGLE

Wilfredo Lam

1943

A group of women with equine or feline faces gazes out at the viewer from a densely packed field of sugar cane and tobacco leaves. Painted shortly after the artist returned to Cuba from a trip to Spain and France, Wifredo Lam’s The Jungle employs the flat space and African mask imagery seen in much European modernism, such as Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avigon. Lam (1902–82) also returned with a renewed interest in his Afro-Cuban heritage, especially in Santeria, the animistic folk religion of his godmother, a Candomblé priestess. In Santeria “the jungle” refers to a sacred space, and the voluptuous forms of the women’s breasts and buttocks hanging like ripe fruits in the trees suggest the papaya, an Afro-Cuban symbol of female fertility. These ambiguous women could be orishas (Santeria deities) or worshippers gathering leaves for a ceremony. While celebrating Afro-Cuban culture, Lam also protested the dominant picturesque representation of Cuban blacks when their real conditions were so horrible, and thus the figures can also be read as laborers or enslaved people escaping the confines of exploitive sugar cane and tobacco plantations. Influenced in part by meeting negritude poet Aimé Césaire, Lam said he wanted to “spew forth hallucinating figures with the power to surprise, to disturb the dreams of the exploiters.”

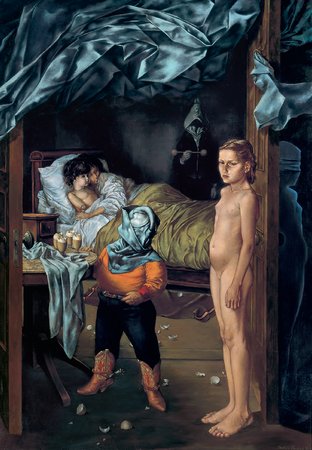

THE GUEST ROOM

Dorothea Tanning

1950–2

A young girl stands on the threshold of a room, naked and unsure. Many anxieties lie within: a homunculus smashing eggs, a woman cuddling a doll, a hooded judge on the edge of darkness. Ten-year-old Patsy, a neighbor’s daughter, modeled for the painting, reluctantly, and her sense of vulnerability, possibly shame at her pubescent body in transition, is clear in her stance and ambiguous expression. The situation is confusing and uncomfortable: is she inviting the viewer in? Guarding the entrance to the room beyond, with its peculiar and frightening denizens? And who or what is the meaning of the blindfolded doppelganger on the other side of the door? What symbolism lies behind the doll child and the broken eggs? In her early work Dorothea Tanning (1910–2012) explored the history of her own dreams, constructing an inner world crowded with symbols and allegory. Doorways frequently appear – perhaps leading to ancient knowledge or the loss of innocence – as do mirrors, hybrid animals and flowers. During Tanning’s long and productive life, she moved away from Surrealism (a label she disliked) towards abstraction, soft sewn sculpture, and literature. To her dismay, her marriage to the Surrealist Max Ernst often overshadowed her own work.

STANDING BY THE RAGS

Lucian Freud

1988-1989

Lucian Freud (1922–2011) focused on portraiture from the 1950s onwards, and in the mid-1960s the nude became an especially significant theme in his work. This painting features a female figure appearing to lean on a mound of artist’s rags. These would have been used by the painter to clean brushes, and a number of the rags feature stains and marks, which also appear like blood or other bodily fluids. Freud was known for portraying his subjects’ bodies with brutal reality, placing emphasis on the sags and strains of the flesh. Despite this, he had no shortage of sitters, regularly painting friends and family, and creating nude portraits of famous celebrities including Kate Moss, while pregnant, and Leigh Bowery. Freud also turned his unrelenting gaze upon himself, producing a series of self-portraits during his lifetime. The dominance of the rags in this painting brings to mind the process of creating the artwork, and the artist’s presence. Standing by the Rags also appears in the backdrop of another painting, Two Men in the Studio (1987–1989), which portrays a male nude and another man beneath bed sheets. Freud’s interest in emphasizing the relationship between artist and model is a theme explored by others in art history including Diego Velázquez and Pablo Picasso, and his realistic portrayal of the nude is in a tradition stretching back to the work of Gustave Courbet.

PUCE MOMENT

Cecily Brown

1997

Amid a chaotic vortex of fleshy pinks and reds, fragmentary glimpses of the human body appear at wildly varying scales: heads with open, gasping mouths jostle for space with arms, breasts, penises and thighs. The overall effect is a combination of debauchery and horror, with every suggestion of orgiastic pleasure rubbing up against intestinal squiggles and bloody crimson waves. In this abstract composition Cecily Brown (b.1969) treats the human body as component parts, never quite allowing a complete figure to become fully legible. Snippets of narrative swim into view: a woman is caressed (or molested) from behind, disembodied hands toying at her nipples and genitalia, while a leering male figure in a black jacket looks on with his buttocks and legs exposed. An atmosphere of voyeurism pervades the canvas, which may reflect the artist’s own take on the traditions of the nude in the history of painting. Brown’s work not only revives the sensual abundance of Rubens’s buxom nudes, as well as de Kooning’s ferocious treatment of the female body, but also addresses these male-dominated traditions in a spirit of both homage and skepticism. The history of the nude returns as semi-digested matter: seductions have become repulsive.