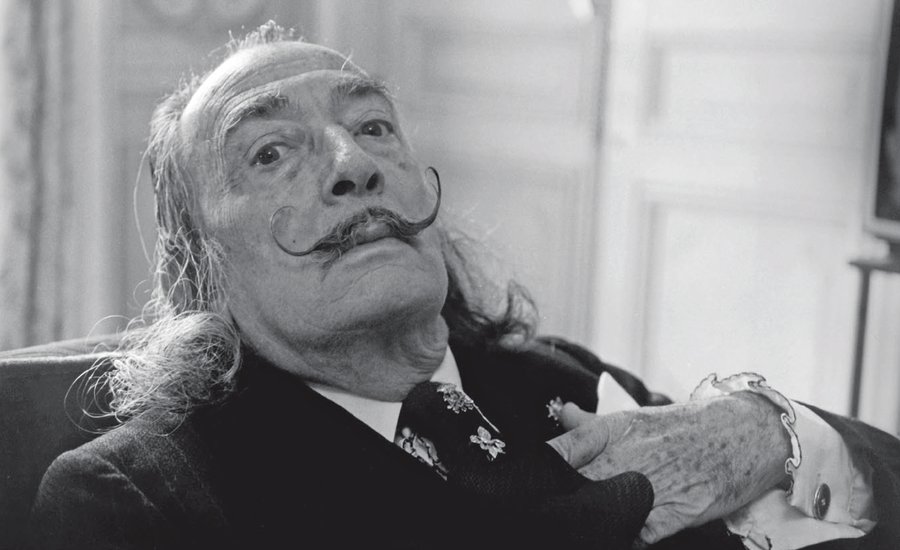

In this excerpt from Noah Charney’s recent Phaidon book The Art of Forgery, the art crimes historian recounts the strange tale of Salvador Dalí and his friend, assistant, and potential forger Antoni Pitxot,raising vital questions about the nature of authenticity and deceit in the realm of art.

Click here to purchase The Art of Forgery from Phaidon.

When The Persistence of Memory, Salvador Dalí’s famous “soft clock” painting, was displayed in New York City in 1934, it caused a huge stir. Dalí (1904–1989) was the talk of the town, hugely popular and in-demand among the literati and the Manhattan art world. A ball was held in his honor to which the inimitable Dalí arrived wearing a glass case around his chest containing a brassiere. Two years later, at the International Surrealist Exhibition, Dalí arrived to give a lecture leading a pair of giant Russian wolfhounds, wearing a deep-sea diving suit and helmet and carrying a billiard cue. Such acts were the bread and butter of the Surrealists. Anything that would turn heads, force double-takes, confuse and induce a sense of wonder was par for the course. And no one lived a Surreal existence better than Dalí.

When Dalí and his wife Gala dressed as the Lindbergh baby and his kidnapper at a social event in New York in 1934, the outraged press demanded a public apology. Dalí duly apologized, but was consequently kicked out of the Surrealist group on the grounds that one didn’t apologize for a Surrealist act. Dalí quit, stating simply “I am surrealism.”

Dalí produced a staggering number of works in many media. The number of projects to which he attached his name increased with his age—and his desire for more and more money—but his lifestyle and declining mental competence seemed at odds with his prodigious output. And no wonder. The Belgian crime writer Stan Lauryssens published a memoir in 2008 of his early career as a dealer in fake Dalí prints, in which he reveals that there were whole industries producing fraudulent works by Dalí, whose lithographs in particular rank alongside those “by” Picasso, Miró, and Chagall as the most-faked of all artworks. Around 12,000 fake Dalí prints were seized in a single investigation. Dalí is the second most frequently forged artist (behind only Picasso), and is known to have signed blank canvases to be filled in later by other artists. He also authenticated forgeries in his style by other artists (it seems that he genuinely believed them to be his), and he may have sanctioned forgeries of his own work in exchange for a share in the profits. Dalí had become an industry—he even designed, among many other products, the wrapping and display stands for Chupa Chups lollipops.

The life of Antoni Pitxot (born 1934) is inseparable from that of his great friend Dalí. Both he and Dalí were born in Figueres in Catalonia, Pitxot a generation after Dalí, and both owned property in Cadaques. Their families were close friends and Dalí was the earliest supporter of the young Pitxot’s work. Pitxot was an award-winning artist himself whose work often features surreal allegories of memory, as does Dalí’s. Pitxot would go on to co-design the Dalí Museum, which was built in 1968, and became the museum’s director after Dalí’s death. Pitxot received the Gold Medal of Merit in Fine Arts from the King of Spain in 2004 for work produced under his own name. However, a conspiracy theory begins in 1966, when Pitxot moved in to Dalí’s villa full-time. Their close personal, artistic and geographical relationship led some individuals familiar with Dalí to believe that Pitxot began painting as Dalí around the same time, sanctioned by Dalí as his own artistic powers started to wane.

There is a clear financial motivation for an artist to keep producing saleable work, especially someone like Dalí who was well-known to be obsessed with money. Fellow Surrealist André Breton jokingly noted that an anagram of Salvador Dalí is “Avida Dollars” (“crazy for dollars”), and Dalí developed carpal tunnel syndrome from signing his autograph so often, knowing that each autograph could be sold. But Dalí was already wealthy, with a steady income from prints of his work, so any decision to secretly allow a pupil to produce works in his name was surely as much about pride—refusing to admit that he had lost his artistic mojo—as it was about money. But this raises the question: if Pitxot was working on behalf of Dalí, making “Dalí” paintings, are these paintings still forgeries? Or are they fakes, since Dalí may have signed the canvas, thereby making authentic a painting by someone else? Certainly the artist is not losing out, as in most forgery cases. But does this action become criminal when a collector or museum buys a painting under the belief that it is a Dalí original?

In principle, such a piece has been offered under false pretenses and its value is decreased. But throughout the history of art most artists have kept—and continue to keep—studios. The master artist would supervise all works produced by the studio but there have always been paintings made “by” an artist—produced from their design and in their studio—that the artist himself has never actually touched. This was not something that artists sought to hide or cover up. It was understood that the master artist would be actively involved in the actual painting only in proportion to what a commissioner was willing to pay. Isn’t the situation with Dalí merely an extended example of the studio system at work? Pitxot was simply acting as Dalí’s assistant, with Dalí’s studio producing paintings that were labeled as “by Dalí,” even though the actual amount of time he spent painting them may have been negligible.

The main objection to such an interpretation is the question of deceit—which in itself may be a case of pride. Perhaps Dalí was reluctant to admit that he was painting less and assigning his projects to his assistant, preferring to maintain the illusion of continued prolificacy even as his skills deteriorated. But although these works may have a tint of disingenuity about them, it is difficult to claim that they are either fakes or forgeries.