In contemporary pop culture, the ultimate marker of success is having your photograph taken by iconic photographer Annie Leibovitz . Leibovitz began her career at Rolling Stone Magazine in the '70s, and then Vanity Fair and Vogue , where her distinguishing portaits earned her critical acclaim. She was deemed a Living Legend by the Library of Congress, and her work continues to be shown in museums internationally.

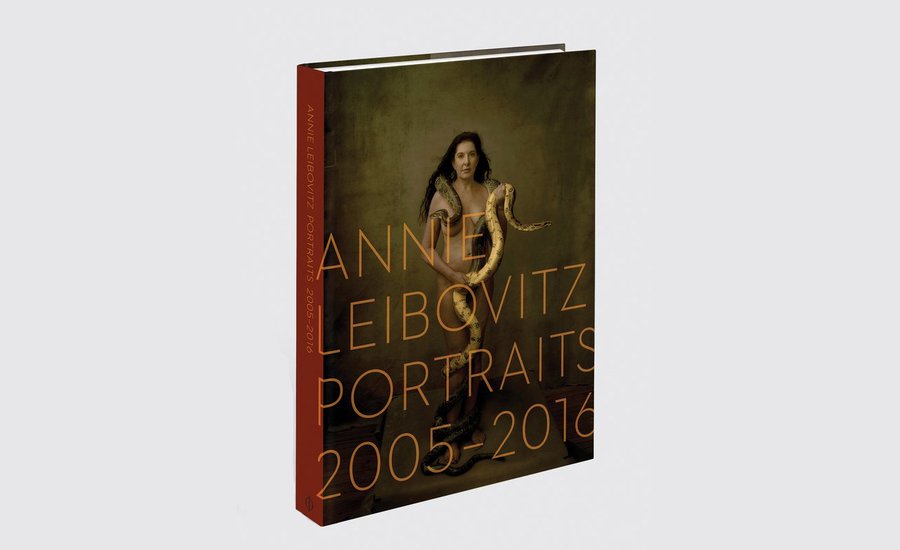

Annie Leibovitz: Portraits 2005-2016 features over 150 portraits of the most influential icons of the past decade, from Serena and Venus Williams to Queen Elizabeth II. The book is a follow-up to her two earlier published titles, Annie Leibovitz: Photographs, 1970-1990 and A Photographer's Life, 1990-2005 . The new collection showcases Leibovitz's masterful eye, and her way of capturing an intimate depiction of some of the most widely-known individuals of our time. In honor of the release of Annie Leibovitz: Portraits 2005-2016 , published by Phaidon , we've excerpted a statement from the artist, in which she writes about her greatest influences, how she connects her personal work to her professional work, switching to digital photography late in her career, and how she came to focus on portraiture.

---

Annie Leibovitz, Image courtesy of Phaidon

Annie Leibovitz, Image courtesy of Phaidon

"All my life, I have looked at and been influenced by photography books—Henri Cartier- Bresson’s The Decisive Moment , Robert Frank ’s The Americans , Diane Arbus ’s Magazine Work , Richard Avedon ’s Observations and Nothing Personal , Jacques Henri Lartigue’s Diary of a Century .

I remember Bea Feitler telling me how she and Avedon created the story in Lartigue’s book. I was lucky to have had several years with Bea. When I met her, in the early seventies, she was the art director of Ms. magazine, which had taken off not least because of Bea’s graphics. A few years earlier, when she designed the Lartigue book and helped Avedon edit it, she was also the co-art director of Harper’s Bazaar , with Ruth Ansel, creating award-winning issues that are emblematic of the sixties. (The Bazaar cover with Jean Shrimpton’s head encased in a pink Day-Glo cutout of a space helmet, one eye winking, is still influential.) Bea was amazing. A whirlwind. She designed Helmut Newton’s White Women and album covers and posters. She redesigned Rolling Stone twice and finished the prototype of the revived Vanity Fair a few weeks before she died. She was only forty-four.

Bea had been very generous in sharing her finely honed understanding of the process of making art. She was particularly firm about stopping from time to time and looking back at your work. She said that you will learn the most from your own work, and by looking back you will find how you need to go forward. That advice made a lot of sense to me. I published a book that covered the first twenty years I worked—1970 to 1990—and later I made A Photographer’s Life: 1990–2005 , which included the years when I was with Susan Sontag .

I realized recently that a great deal of work had accumulated since 2005. History takes over when you do this for so long. I wanted to stop and take a look and make a new book, and I knew what the end of the book would be. It would end with a portrait of Hillary Clinton in the White House. I planned my shoot with her. I spent a lot of time imagining what desk Hillary would choose to be her desk in the Oval Office. Was one of Eleanor Roosevelt’s desks available?

Then Hillary lost. My imagined ending, which was really an extension of something, or a beginning, belonged to a view of the world that had been rather dramatically shattered. The years 2005 to 2016 now seemed like a discrete era. They were the years when Barack Obama held high public office, as a senator and then as president. And I guess you could say they were years when the culture was shifting in ways that we didn’t quite take in. I wasn’t thinking about any of that when I decided to do the book. I just wanted to assess what my work looked like.

Annie Leibovitz: Portraits 2005 - 2016

is available on Artspace for $89

Annie Leibovitz: Portraits 2005 - 2016

is available on Artspace for $89

A Photographer’s Life is the only book I ever made that combines personal pictures with assignment work. They collide and converge. Susan had just died, my father had died, my three children had been born. I was emotionally raw, and perhaps because of that, the personal material became the most prominent element in the book. This caused me some concern after it was published, since I realized that I had laid my family and close friends open to scrutiny, but when I was making the book, in a driven, obsessive way, I somehow hadn’t imagined that other people would be looking at it.

I am proud of A Photographer’s Life . It seems to me to be the most powerful collection of my work. What it did in terms of directing me forward was that I realized I needed to concentrate more on my portraits. I don’t lack portrait assignments, but I began trying a little harder to persuade editors to give me the subjects I wanted. I started to work on a series of portraits of artists in their studios. I photographed Jasper Johns and Ellsworth Kelly . I went to New Mexico to make portraits of Susan Rothenberg and Bruce Nauman .

There were also independent projects that generated portraits. One of them was Women , an updating of a book and exhibition that Susan Sontag and I had created in 1999. I didn’t want to do another book about women, but I had always thought I would revisit the subject. The form it took this time was a series of pop-up installations in ten cities. We would come into town and install the show in an architecturally interesting spot—an old Victorian hydraulic power station in London; a World War II airplane hangar on the Presidio in San Francisco; a grand, crumbling eighteenth-century house in Mexico City; an Art Deco building that had been turned into a women’s prison in New York City. The installation would be up for four weeks and then we would move on. We added new portraits as the show traveled from city to city. I was able to photograph women I admired but who were not, because of timing or whatever, subjects that the magazines I work for wanted right then. Malala was one of the women I photographed purely for myself.

As I laid out the basic sequence of pictures for what would become this book, I found myself putting in some portraits that had been taken before 2005 but hadn’t made it into A Photographer’s Life because the focus there was so much on personal pictures. For instance, the photographs of J. K. Rowling and Pete Seeger and Leonard Cohen were taken in 2000 and 2001. I also included pictures from Pilgrimage , a book that has no people in it, although the pictures have portrait-like aspects. The subjects are things and rooms and landscapes that are associated with people from the past who mean something to me: Virginia Woolf’s writing desk, a page from Emily Dickinson’s herbarium. Pilgrimage stands on its own, but I like to see those kinds of projects folded into the body of the work. Pilgrimage is also pertinent to the portraits because it was an exercise in photographing the places that people inhabit.

I am not by nature a studio photographer. When I look at the early work I did for Condé Nast, in the eighties, I see myself struggling hard to deal with that. I was enamored with what Richard Avedon and Irving Penn did in the studio, but it took a long time for me to come to terms with it for myself. I always prefer to be in a place that has something to do with the subject. The Sally Mann portrait is an excellent example of that. The shoot was more complicated than usual because I was photographing another photographer, which is always a little awkward, and in this case the other photographer was closely associated with the setting—her farm in the foothills of the Blue Ridge Mountains of Virginia. It is her turf and she is protective of it. She grew up on the farm. She raised her children there. Her most well-known body of work, Immediate Family, as well as much of her later work, was made there. It is her magic place.

Sally was reticent about being photographed, and we had only a day to work together, but we had exchanged a lot of notes via e-mail before I got to the farm. In the late afternoon, I summoned my courage and said that maybe we could go down to the cabin on the river and look around. The cabin and the river are at the very heart of Sally’s work. It took everything I had to ask her if I could photograph her there. I didn’t go near the river itself. I stuck by the cabin door. She sat on the step, and the history of every moment her family spent there went into that moment. That is what you see.

Location is an integral part of a picture. Not as background or decor. The history of a place, its sounds and smells, in uences a picture in ways that are impossible to achieve in a studio. The place in Mexico where I photographed the women’s rights lawyer Andrea Medina Rosas, for instance, is hardly even visible in her portrait, but it is crucial to the picture. We had gone out early in the morning to a spot at the far edge of Mexico City where pink crosses are erected to memorialize the murdered women whose bodies have been found there. Andrea defends victims of sexual violence. Being in that place that morning informs the picture. Her knowledge of what happened there is in her face.

I’m not a good director. I rely on the subject to project something, to collaborate in the picture, and what they are thinking a ects that. Michael Bloomberg, who was just completing his tenure as mayor of New York when I did his portrait, is proud to be sitting in the bullpen of his office at City Hall. Kathleen Kennedy is feeling confident at the back of the soundstage. It is part of her. I didn’t need to go on the Star Wars set.

The portrait of Venus and Serena Williams embracing would probably have had more of an edge if it had been taken in one of their houses rather than in a nearby studio, but I love looking at it anyway. It was a picture I had wanted to take for over a year, ever since I watched them play a semi nals match at the US Open. Serena won, and at the end the sisters gave one another a great, loving, erce hug at the net. The next morning there was a full-page picture of the hug in the New York Times . I ripped it out and put it on the refrigerator for my daughters to see when they woke up.

I often wish that my pictures had more of an edge, but that’s not the kind of photographer I have come to be. There are all kinds of circumstances that determine the outcome of a single shoot. The edge in my work is probably in the accumulation of images. They bounce off one another and become elements in a bigger story.

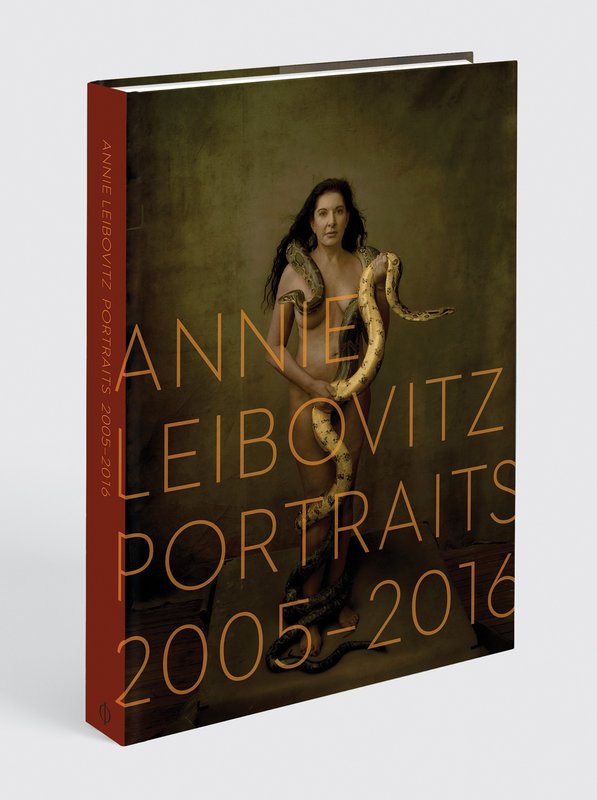

Caitlyn Jenner, Malibu, California, 2015 by Annie Leibowitz, photograph courtesy of Phaidon

Caitlyn Jenner, Malibu, California, 2015 by Annie Leibowitz, photograph courtesy of Phaidon

The story in this book, or at least most of it, has been told with a digital camera. I began using digital cameras in 2006. It is not photography the way I started taking pictures. It is something else, another way to look at things, but it is photography, and certainly no less “real” than black-and-white photography. I was a little embarrassed by it at rst, but I have come to embrace it, maybe because I was never much of a technical photographer anyway. I was always more interested in content.

On the one hand, my fascination with the new technology makes me want to call myself a conceptual artist who uses photography. On the other hand, I have a very traditional approach to what I do. I’m always aiming for a portrait that will stand the test of time. And no matter what equipment you use, it is hard to say how a session will go. The portrait is always dependent on the moment."

- Annie Leibovitz