Famous for angular, often brightly colored furniture, striking graphic designs, and an overwhelmingly Mondernist approach to both aesthetics and lifestyle, the Bauhaus is unquestionably one of the most influential art movements to come out of pre-war Europe. In this excerpt from Phaidon’sArt in Time, we delve into the faction’s early history and overarching goals—with a eye to the ways in which their approach continues to impact artists and designers to this day.

Primarily a school of art and design, the Bauhaus (literally a “house for building”) was founded in Weimar, Germany, in 1919 by the architect Walter Gropius. Initially funded by the democratic Weimar Republic that had emerged following World War I, it closed in 1933 under pressure from the Nazi regime. The modernity, abstraction, and international influence of the school threatened the Nazi belief in uniformity over creativity, conformity over innovation, and nationalism over tolerance.

Running courses on everything from wall painting to furniture, textile design and theatre, it was a fertile environment for cross-disciplinary innovation, run on a medieval workshop basis where “masters” such as Wassily Kandinsky (1866–1944), Paul Klee (1879–1940), and Oskar Schlemmer (1888–1943) would develop work alongside their students. Reconciling values of high-quality craftsmanship with modern industrial progress, and of beauty with function, Bauhaus artists developed highly original pedagogic practices that were intended to benefit the individual as a whole, from breathing exercises to the theories of pattern-making.

Paul Klee's Ancient Sound, 1925

Paul Klee's Ancient Sound, 1925

Klee and Kandinsky had been associated before the war through Klee’s marginal involvement with Kandinsky’s expressionist group Der Blaue Reiter; both had an in interest in music, seeing it as a nonrepresentational art form that could inspire pictorial abstraction. Klee was employed at the Bauhaus from 1920 as a teacher on the preliminary course and as master in the bookbinding and stained glass workshops. Kandinsky joined in 1922 as master in the wall painting workshop.

In Ancient Sound, Klee uses oscillating tiles of color that recall stained glass to suggest resonating tones of music, the hand-drawn forms creating a composition that is rhythmic but not mechanical. Its designation as "ancient" suggests the overriding insistence on transcendental values at the core of the Bauhaus.

Wassily Kandinsky's Several Circles, 1926

Wassily Kandinsky's Several Circles, 1926

Kandinsky’s Several Circles seems to relate to his 1926 textbook, Point and Line to Plane, in which he described the “point” (an “ideally small circle”) as the purest and most basic element of painting, motionless in itself but with the potential to create a moving line or a static plane. Circles, according to Kandinsky, would appear to shift when placed in tension with other forms, and the cosmic appearance of Several Circles is suggestive of his desire to reconcile spirituality and logic.

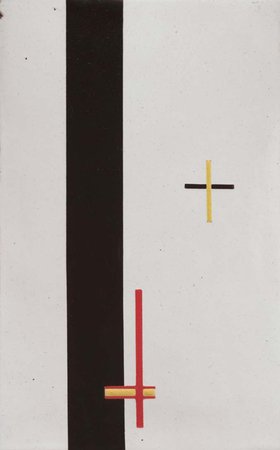

Lázló Moholy-Nagy's Construction in Enamel 2, 1923

Lázló Moholy-Nagy's Construction in Enamel 2, 1923

Specifically challenging the handmade, László Moholy-Nagy’s (1895–1946) enamel Constructions were made to the artist’s design by a sign factory; they were ordered by telephone, their compositions dictated with the assistance of graph paper and the factory’s color chart. The industrial materials and production demonstrate the possibilities of producing art that was available and applicable to a mass market, ideas emblematic of the Bauhaus.

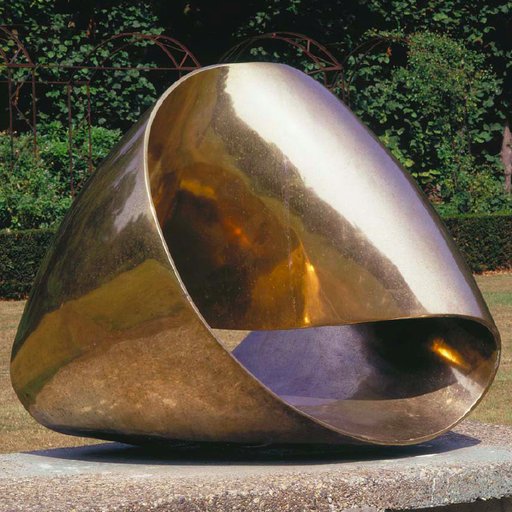

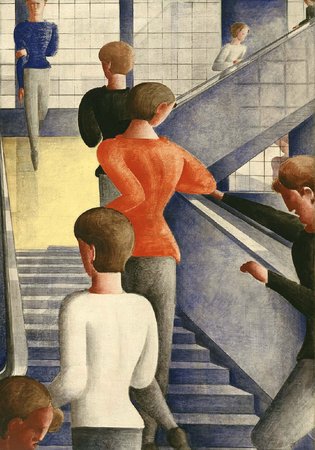

Oskar Schlemmer's Bauhaus Stairway, 1932

Oskar Schlemmer's Bauhaus Stairway, 1932

It was not until the Bauhaus moved to a new site in Dessau in 1925 that Gropius was able to design a building specifically for the school, and it is the main staircase of this modernist structure that Schlemmer depicts in his Bauhaus Stairway. The scene’s bustling community atmosphere, with male and female students rubbing shoulders, works in conjunction with the grid lines that describe the building’s glass-tiled exterior. The figures are schematically rather than realistically modeled, and reflect Schlemmer’s theatrical costume designs: the man at the top left appears as a dancer, en pointe and perfectly balanced.