Since its inception, the New Art Dealers Alliance has been one of the art world’s most reliable mavericks, using its Miami fair (and now New York and Cologne offshoots) to launch fresh talents into the art landscape. But while today they’re a fixture of the art calendar, the story of their improbable rise is surprisingly little know. Here, to mark this year’s edition of the flagship Miami fair, is the origin saga of NADA.

2002

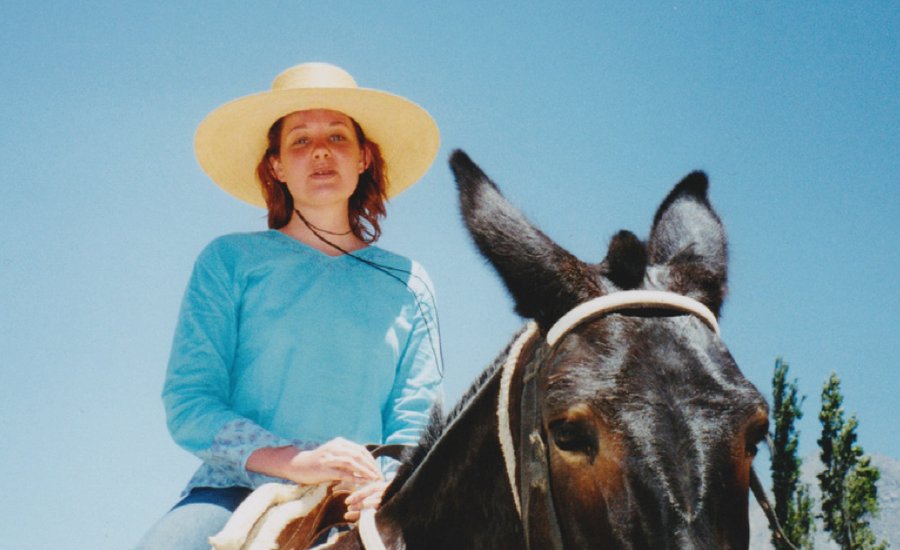

NADA co-founder Sheri Pasquarella

NADA co-founder Sheri Pasquarella

Following a trip to Chile, where a burro ride up the Andes occasioned her to reflect on the alienation of the increasingly professionalized art world, the gallerist Sheri Pasquarella separately conspired with the young dealers Zach Miner (then at Gagosian), John Connelly, and Zach Feuer to co-found a collective devoted to galvanizing a community of art workers who were looking for a more authentic context.

2003

Adopting the name of the New Art Dealers Alliance, the quartet called a meeting of other young dealers at Chelsea’s Half King pub to set the group’s agenda—the first of many booze-fueled gatherings that helped shape NADA’s work-hard-play-hard ethos. It was then that they decided to launch an art fair, holding their premiere edition with 35 exhibitors at the Lincoln, a mixed-use building three blocks away from Miami’s Convention Center, to coincide with the one- year-old Art Basel Miami Beach.

2004

After sales surpassed expectations in the first fair—Zach Feuer says he made as much over

its four days as he did over the entire rest of the year—NADA doubled down, moving to a larger space in downtown Miami’s Ice Palace Film Studios. Equally encouraged, gallerists returned with a vengeance, and found savvy emerging-art collectors like the Dictrows (and institutional bigwigs like the Brooklyn Museum’s Arnold Lehman) eager to buy up their wares—even when these included tough fare like Christoph Buchel and Gianni Motti’s Guantanamo Initiative. The fair’s Friday night party at the Sagamore began to achieve epic dimensions of glorious excess.

2005

Now under the leadership of new director Heather Hubbs, NADA returned with

even more galleries— hailing from as far as Turin, Tokyo, Athens, and Rio—and the new sponsorship of the (now-defunct) Fernwood Art Investments company. (Over 500 exhibitors applied for the 80 available slots.) Takashi Murakami’s Kaikai Kiki made its

first appearance, the lights blinked off and on during the opening night, and the New York Times’s Roberta Smith enthused that “the best food of any of the fairs comes from a Cuban- food truck parked out back.”

2006

Hailed as “the immensely successful NADA fair of hip young dealers” by critic Walter Robinson, the fourth edition debuted with the curatorial backing of the New Museum and financial support from Altoids, bringing in over 25 new exhibitors. Katherine Bernhardt had a buzzy turn at CANADA. Everyone continued to love the hammocks set up outside, lounging and people- watching in the sun.

2007

How cool was NADA in 2007? Indie darlings Deerhoof performed at the opening night preview against a devilish backdrop by artist Ken Kagami; Gang Gang Dance played the after-party, sponsored by Nike. “The Office” star B.J. Novak even made a celebrity cameo. Now one of 20 Miami fairs, NADA also exerted a narcotic pull on normally self- contained collectors, who rushed like a Viking horde upon the booths of art by Matthew Day Jackson and other soon-to-be-stars at the opening bell.

2008

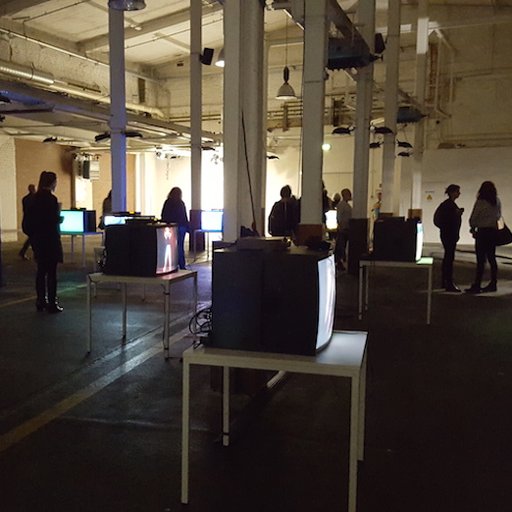

Auratic musician Panda Bear

Auratic musician Panda Bear

CRASH! The global economic cataclysm cast a Pompeii-worthy pall over the Miami fair proceedings...but NADA, ever resourceful, adapted to the low-rent moment with a proliferation of works on paper and printed goods, together with breakout debuts by artits like Keltie Ferris and Debo Eilers. The party, however, didn't miss a beat, with performances by the legendary Panda Bear (and sponsorship again by Nike)

2009

Looking to reduce costs for its pool of young galleries who were struggling amid the financial crisis, NADA moved to more affordable space at the retro-chic Deauville Beach Resort in North Miami-which provided the added benefit of discounted hotel rooms for exhibitors. Confidence had begun to return to the market after a series of successful New York auctions, and dealers allowed themselves to have fun, setting up surreal installations all over the grounds of the beachfront resort (and holding some pretty wild parties in their hotel rooms too).

2010

Great Recession? What Great Recession? Opening with 89 exhibitors-a 10 percent increase from the previous year- and a swanky party at the deluxe neighboring Canyon Ranch spa, NADA drew a rabid swarm of determined collectors that bought out many booths within the preview's first hours. The fair also launched NADA Projects to offter smaller, cheaper booths for more experimental presentations...and buyers snapped these up too.

2011

"NADA has gotten better and better," the New York Times declared amid head-turning showings by future starts like Mira Dancy, Josh Kline, Neïl Beloufa and Ella Kruglyanskaya. Meanwhile the YouTube art sensation known as Hennessy Youngman delivered a discursus on art history while wearing a Spider Man hat (thesis point: "cocaine is the eternal friend of [artists] who need to do shit"), and NADA went online for the first time, producing a virtual preview of the fair as an appetite-whetting teaser for its ravenous collector audience. NADA Hudson debuted this year as well, spinning off the youthful fair to the burgeoning art enclave of the Hudson Valley.

2012

What's that fresh smell? NADA Cologne

What's that fresh smell? NADA Cologne

For its 10th year, NADA went global- the year saw the premiere of NADA Cologne, its collaboration with the world's oldest contemporary art fair, and NADA New York, which took over Center 548 in Chelsea.

2013

This may have been this year when the Kimye-ification of the Miami art-fair circuit was completed- luxury brands, celebrities, real estate developers, and pop starts with the scantest relationship to art other than its proximity to money swarmed the city like Asian longhorned beetles. It was also the year that publications like the New York Times and Complex magazine flooded the zone with wall-to-wall Miami art coverage, chronicling every boldface-name appearance. Amid this maelstrom, NADA maintained its commitment to the small, the weird, and the not-so-easily assimilable, making starts of offbeat artists like Borna Sammack and even the fictional Vern Blosum.

2014

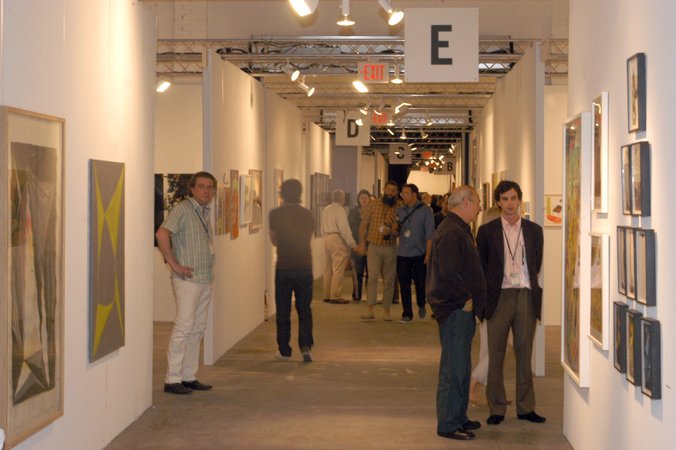

The BAM booth at the fair

The BAM booth at the fair

Demonstrators toting "I Can't Breathe" and "Black Lives Matter" placards shut down the I-195 highway to protest race-based police brutality this year as a climate of social unrest mixed uneasily with the conspicuous consumption at Miami's fairs (which by most accounts were more flush than ever). Meanwhile, art began taking on strange new forms, like the virtual-reality suite that the artist Jon Rafman set up for NADA in his hotel room. Instagram had officially become the visual agora for the art community, and founder Kevin Systrom made an appearance at the fairs with curatorial godhead Hans Ulrich Obrist. It was the last year NADA would remain at the Deauville, and the beginning of a new era.

2015

The Fontainebleau Hotel. C'est magnifique, non?

The Fontainebleau Hotel. C'est magnifique, non?

Comfortably ensconced in the tony setting of the Fontainebleau hotel for a change, NADA returned this year with 88 exhibitors for the main fair and 17 for its new Project section, representing 32 cities from 15 nations. Once an against-the-odds challenger to the Basel monolith, NADA Miami Beach had become a cornerstone of the Miami fair regimen—and the most successful alternative fair in the world. You've come a long way, baby!