As the site where paintings are slathered and sculptures are wrought, the artist's studio is a locus of widespread fascination. It's also a very complicated place. As artists have evolved over the 20th century to embrace installation art, performance, relational aesthetics, and other site-specific approaches that necessarily occur outside of the studio—ushering in what has been called a "post-studio condition"—this onetime site of solitary creativity and material exploration has become a meeting place, where a visit with a curator or critic can turn into a professional negotiation, planning, and development. At the same time, art enthusiasts have an obsessive fascination with the mythology of the artist's studio, which is documented online and in programs like PBS's Art21 series with a relish that falls somewhere in between the reverent preservationism of a nature documentary and the romantic escapism of a spread in Vogue.

An extreme example of this reverential treatment: painter Francis Bacon's studio has been preserved at Dublin's Hugh Lane Gallery since 1998, a huge project that entailed the work of a team of archeologists, conservators, and curators who carefully mapped, transported, and recreated every detail down to the dust that had collected since the artist's death in 1992. Elsewhere, this fascination has crept into temporary exhibitions: Urs Fischer showed his entire studio as a readymade sculpture in Venice's Palazzo Grassi for his "Madame Fisher" show there in 2012. Who knows—maybe a century from now, collectors will be snatching up the fractured remains of Ai Weiwei's Beijing atelier at auction.

But where does the model of the artist's studio, and our fascination with it, come from? Like art itself, the artist's studio is always a reflection the spirit of the times. Below is our history of the evolution of the artist's studio in Western art, from the Renaissance to today.

15th CENTURY: THE BOTTEGA AND THE STUDIOLO

Our contemporary studio model can be traced back to the Renaissance, when private patrons supplanted the centralized infrastructure of the Church that had dominated the production of art in the Middle Ages, when artists worked within monasteries or similar religious institutions. In this new era, artists began developing close and long-lasting relationship with individual patrons, for whom they would create commissioned work for many years, painting altarpieces, murals, portraits of their patrons' household, and other commissioned projects.

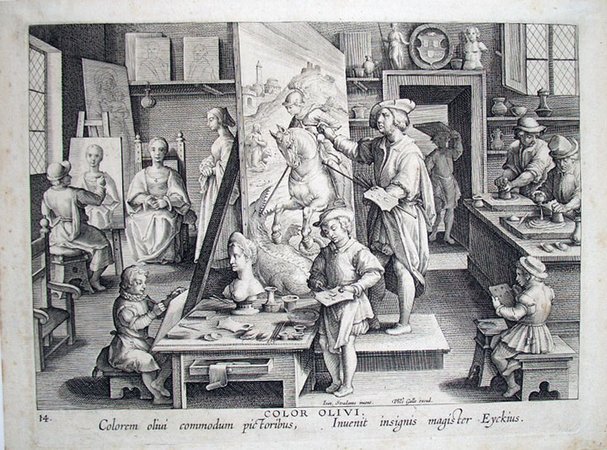

The artist's very livelihood became dependent on their patron's beneficence, and the reputation of one was tightly intertwined with the relationship of the other. The artist's work was carried out in the bottega—the workroom—as opposed to the studiolo, a word that has the sense of a study, a room for contemplation, which would be a separate space. Both were often housed in the same building. Artists entered as apprentices, doing menial tasks until they proved themselves talented enough to learn the art of their masters.

17th CENTURY: STILL LIFES IN SLOW-DRYING PAINT

Later, and further North in Europe, painters' attention shifted from the visages of their wealthy patrons to still lifes and self-portraits (though commissioned portraiture remained a staple of the artist's paycheck). Figures like the Flemish master Jan van Eyck made important developments in oil painting techniques, which allowed for the careful and hyper-realistic depiction of everyday objects—often inflected with allegorical meaning—over a slow, drawn-out process of mixing, layering, and drying.

The studio became a reflexive space, a combination of the workroom and the study where the act of contemplation was incorporated into the process of painting itself. This is especially true in the famous case of Rembrandt's series of more than 50 self-portraits produced over the course of his lifetime, despite the fact that the term "self-portrait" didn't actually exist in the artist's lexicon until a century later.

19th CENTURY: THE ATELIER AND THE ACADEMY

Despite changes in artistic attitudes and predilections, the basic format of the artist's studio stayed largely the same from the Middle Ages through the 1800s. Ateliers consisted of one artist and a group of dedicated students who graduated from apprentice to journeyman to master, at which point they started their own workshops. The only competition to the atelier model came in the French Academy system, beginning with the founding of the École nationale supérieure des beaux-arts in Paris in 1816, which organized own exhibitions (known as salons) to support, critique, and analyze artistic developments. The Academic salons were the major European art events of the century, and formed the foundation against which avant-garde artists like Edouard Manet would react in the early 1900s.

1870s: EN PLEIN AIR

In the 19th century, the beginnings of industrial production had huge ramifications for artists. Whereas artists of the past centuries had had to produce their own paints, laboriously mixing ingredients—often evident in the mixing bowls visible in the background of Rembrandt's aforementioned studio self-portraits—now paint was readily available in aluminum tubes which could be purchased at a store, meaning the same quality and quantity of ingredients was available across the continent; paint became newly available in tubes for the first time, as did lightweight portable easels. Industrial manufacturing also meant that materials like brushes and easels, in addition to benefitting from improvements in design, could be produced quickly and efficiently.

This environment produced an entirely new way of painting, which came to be known as en plein air—literally "in open air." Across Europe, painters packed up their foldable easels and boxed sets of factory-made paints and brushes and trekked out into the continent's pastoral landscapes to paint nature in all its glory. Artists no longer had to wait for wealthy patrons to commission portraits before they could get to work; they could enjoy painting as an activity of edification and leisure—l'art pour l'art, or "art for art's sake"—on their own. This milieu directly influenced the development of artists like Claude Monet and John Singer Sargent in the mid 1800s. In the 1870s, Monet, in fact, equipped a house boat to act as a floating studio, from which he painted landscapes and portraits of friend Manet and his wife, Suzanne.

1960s: "THE FACTORY"

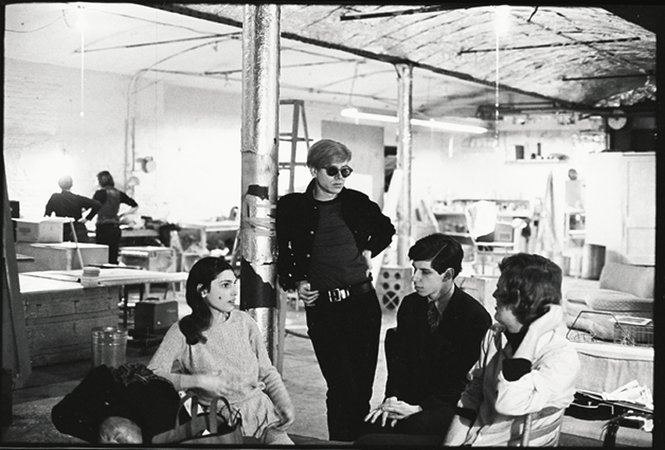

In 1960s New York, Andy Warhol innovated the artist's studio model by combining artistic production with Henry Ford-indebted mechanization in his studio-slash-party space the Factory, as it was known. Warhol was the king of the silkscreen, a way of quickly printing images that could be repeated over and over. The main innovation of Warhol's studio was the fact that it was known equally for its amphetamine-fueled parties and rotating cast of personalities as it was for the art it produced. This was the advent of the artist as a brand—an idea that Warhol shrewdly engaged in a meta-critical take on popular modern American culture. Of course, the '60s also saw artists like Donald Judd engaging with actual factories as well, shopping out the fabrication of minimal, industrially-inspired sculptures to professional fabricators and manufacturers.

1980s—TODAY: THE ACTUAL FACTORY

Compared to Warhol's Factory, Jeff Koons's New York studio looks like an Apple plant. OK, that might be an exaggeration, but the professional polish on Koons's Cheslea art factory is unprecedented. The artist, who will enjoy his first major museum retrospective at the Whitney Museum of American Art starting on June 27th, employs literally hundreds of assistants who are specialists in painting, casting, finishing, computer graphics, and so on; each the master of one very refined, and very specific, skill. Many are struggling artists themsleves, some of whom go on to have their own successful careers. In a field ruled by ambition, of course, the turnover rate can be high: Koons's team is regularly posting ads on job listing sites looking for more employees to. If you're a recent grad of a top MFA program, your chances are good! Although these days, you're more likely than not to end up as an unpaid intern. Which really isn't bad: just think of it as the conetmporary parallel of an apprenticeship in a Renaissance bottega.