More so than Post-Impressionism or Post-Modernism, the genre of art known as Post-Minimalism is a particularly squirrely one to wrap one's mind around—after all, what is there beyond Minimalism's elegant reduction of art to pure form? The critic Roberta Smith may have put it best a few years ago when she described it as “that unruly early ’70s mix of Conceptual, Process, Performance, installation, and language-based art." But what links all these divergent approaches together?

An important flashpoint in the art historical canon of the 20th century, Post-Minimalism got its first mention by noted art historian Robert Pincus-Witten in 1971, when American artists began reacting to the Minimalist tendencies that had dominated the contemporary-art conversation of the '60s. The Post-Minimalists—among them Keith Sonnier, Richard Serra, and Lynda Benglis—wanted to counteract Minimalism’s austere and at times opaque forms and ideas with more malleable, interpretative, and rangier works of art.

With Serra’s blockbuster Gagosian Show having been extended through February 8, Pace's show of Sonnier's recent light sculptures up through February 22, and Benglis's recent work on view at Cheim and Read through February 15, the genre is having a bit of a moment in New York. Here's a breakdown of some of Post-Minimalism's most salient elements.

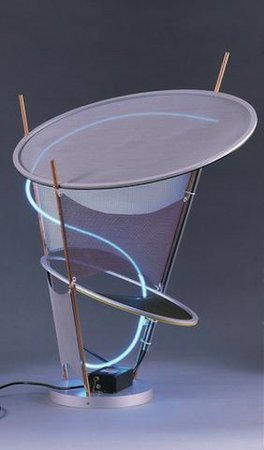

THE IMPERSONAL BECOMES THE PERSONAL Keith Sonnier's Chandelier Project (2000)

Keith Sonnier's Chandelier Project (2000)

Unlike the unforgiving, mysterious works of the Minimalists—rigid forms often made by others– the Post-Minimalists used a similar aesthetic while also trying to put a more personal stamp on the work. In short, Post-Minimalists tried to find expression in what previously had been used as expressionless materials and forms. Sonnier’s neon works are not linear and stoic like Dan Flavin’s similar counterparts, but are in fact rather sensual. (His sometimes created his works in the exhibition space just before they were shown.) His Chandelier Project, to name one example, highlights how even industrial materials like neon and aluminum can be manipulated into erotic forms: Sonnier’s sculpture tilts on its axis, suggestively off-kilter, as a blue-lit streak snakes around it.

Eva Hesse is often labeled a Post-Minimalist, and while her work makes use of the grid and repetition—she was briefly labeled a Minimalist—the presence of the artist’s hand becomes just as much a part of her project over the arc of her career. The distinct sexualized nature of her work, too, was part of the Post-Minimalist project, in defiance of the asexual forms of Minimal art. Lynda Benglis was on the forefront of that trend: works like her Napoleonville challenge how to eroticize the Minimal object, as in this banana-shaped sculpture made of glass.

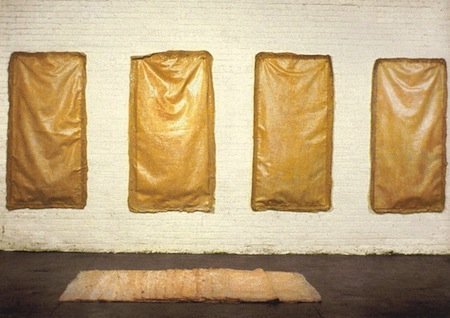

ART ON THE CHEAP Eva Hesse's Aught and Augment (1968)

Eva Hesse's Aught and Augment (1968)

Post-Minimalists distinguished themselves from the Minimal artists who just preceded them by using more unusual materials, often of shoddy quality that allowed for more varieties of expression. Drooping, sagging, bending—these were all seen not as detrimental qualities, but means of displaying uniqueness of the materials and the artist’s vision. As Robert Morris wrote of Post-Minimal art’s "anti-form" in 1968: “Random piling, loose stacking, hanging, give passing form to the material. Chance is accepted and indeterminacy is implied since replacing will result in another configuration…. It is part of the work's refusal to continue aestheticizing form by dealing with it as a prescribed end." A major issue curators and collectors face with Hesse’s works today lies in the fact that many of her materials have worn down almost beyond repair, since she often used latex and plastics in her work. (The philosopher/critic Arthur C. Danto wrote of her 2006 retrospective at the Jewish Museum of "the discolorations, the slackness in the membrane-like latex, the palpable aging of the material.”) Sonnier, too, occasionally used latex, as well as more easily degradable materials such as cheesecloth and silk.

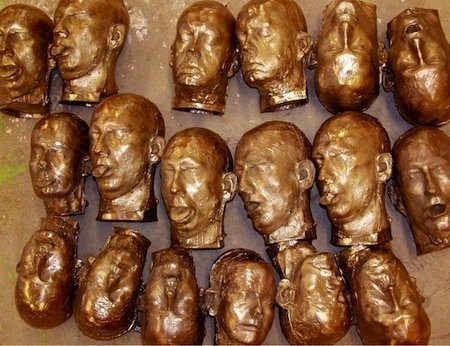

INDEFINABILITY AND CROSS REFERENCES Bruce Nauman's Studio Floor Detail (2006)

Bruce Nauman's Studio Floor Detail (2006)

Part of what makes Post-Minimalism much harder to pigeonhole than its forbearer is that it encompasses so many other concurrent movements: Land art, Process art, performance art, Conceptual art, body art, site-specific art… the list goes on. Bruce Nauman is often name-checked as an influential Post-Minimal artist, although he is also generally thought of as an important figure of Process Art. And the same goes for Richard Serra, who bridges the Minimal and the Post-Minimal, while also commonly referred to as a Process artist. It’s pretty much a given that any Post-Minimal artist shares equal footing in another movement of the time since they often fall under the umbrella category. Given that many Post-Minimalists were chasing after very different, often opposing, ideas while still being a part of the same generational current in 20th century art, it's a remarkably protean and expansive genre.

THE POSSIBILITIES ARE LIMITLESS Robert Smithson's Nonsite (Essen Soil and Mirrors (1969)

Robert Smithson's Nonsite (Essen Soil and Mirrors (1969)

In breaking with the anonymous, unyielding works of Minimalism that were enshrined within the gallery space, Post-Minimalists sought to expand what and where art could be, and what effects the elements could be allowed to inflict upon it. Land art and site-specific art are important flashpoints, in that the kinds of forms generated by Minimalism could take on larger, otherworldly significance when created to interact with a specific environment, or changed by nature. In this way, pieces held in the gallery space too were also put at the mercy of the elements: the effects of gravity, light, and wear were encouraged in Post-Minimalist artworks, which were allowed to distend and morph over time—allowing artists a way to break out of the strict guidelines of Minimalism and open up not only viewers but the work itself to a wholly unpredictable experience.