Included in a recent show of work by the Croatian artist Mladen Stilinovic was a piece composed of a square of fabric emphatically hand-painted with the words, "I AM SELLING M. DUCHAMP." Stilinovic is a little-known avant-garde filmmaker, never classically trained but highly active in his native Yugoslavia in the 1960s. What does it mean for Stilinovic to invoke Duchamp, the French artist and conceptual forefather of so much of the 20th century's art, who is widely considered the most influential artists of the past hundred years?

For a cynic, the biggest takeaway from Duchamp's legacy might be that, since his death in 1968, no artist has done anything new. Which would, in part, be true: Duchamp's impact on art could be compared to Einstein's on physics, with all ongoing developments simply elaborations of his foundational principles. But that aside, for the artists who came after him, citing Duchamp suggests a certain attitudinal sense of humor with a biting intellectual edge.

So what, exactly, did Duchamp do? Those whose knowledge of his achievement stops with his famous Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2 (1912)—a early painting in a definitively Cubist style—will be surprised to know that the iconoclastic Frenchman continuously exploded one convention after another over the course of his long career. To better understand exactly what Duchamp wrought, we took a look at his greatest hits—and how they continue to chart new directions for art today.

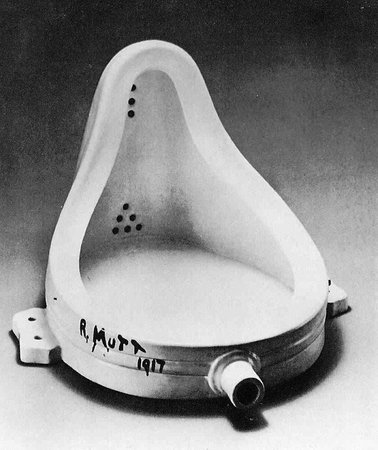

THE READYMADES (1915–1921): CHOICE IS CRUCIAL

In explaining how he conceived the concept of the "readymade"—an object made into a work of art simply by the act of the selection of the artist—Duchamp had a surprisingly logical and pithy explanation: "When an artist paints using a palette he is choosing the colors. So choice is the crucial factor in a work of art." Duchamp's earliest readymades—a urinal, a snow shovel, a barbed coat rack—highlighted this act of choosing, but also inflected the artist's choice with conceptual trickery by titling the works Fountain, In Advance of the Broken Arm (En prévision du bras cassé), and Trap (Trébuchet), respectively. In other words, not only the act of the artist's selection, but also his or her conceptual framing of the artwork as an idea, became the main thrust of the work.

Many argue that this notion gave birth to the entire epoch of Modern art, wherein ideas became paramount over ideas of taste or beauty. (In a 2004 survey, Fountain was voted the most influential artwork of the 20th century.) To extend this conceptual overture to the present moment, the recent idea that of the curator-as-artist—wherein the selection of artworks is considered a creative act—is directly in line with Duchamp.

L.H.O.O.Q. (1919): QUESTION AUTHORITY

A certain irreverence toward art history is actually a good thing, as Duchamp's 1919 appropriation of Leonardo da Vinci's world-renowned Mona Lisa showed. In order to move beyond the historical past, after all, one must be willing to eschew its most celebrated icons. Whereas avant-garde movements of the 20th century were propped up by the dramatic political and ideological shifts enveloping Europe at the time, artists now have embraced the need to consistently and continually question the established norms of fine art. The most famous example of the Oedipal spirit in art came in 1953, when Robert Rauschenberg erased a drawing by Willem de Kooning (and titled it Erased de Kooning, no less).

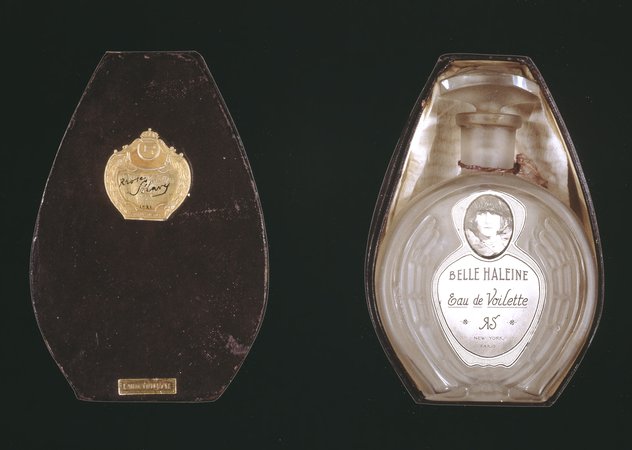

RROSE SÉLAVY: IT'S GOOD HAVE A FRIEND

Duchamp infamously invented a female alter ego, Rrose Sélavy (pronounced "Eros, c'est la vie," or "Eros is life"), who reappeared throughout his oeuvre, often "co-signing" his works. Sélavy originated in a series of photos that Man Ray took of Duchamp dressed as a woman, one of which appears on the label for his 1921 work Belle Haleine, Eau de Voilette, a perfume bottle in its original box. As we recently explored here on Artspace, the alter ego is a trenchant aspect of contemporary art—think of the recent controversy surrounding the Yams Collective's withdrawal from the Whitney Biennial because of artist Joe Scanlan's adopting of a black female identity (fictional artist "Donelle Woolford") as an avatar.

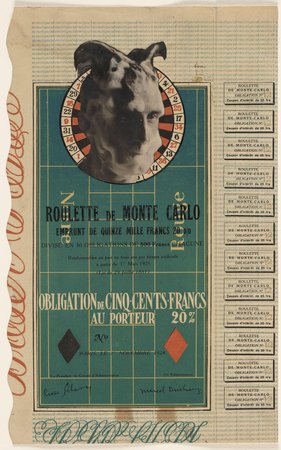

OBLIGATIONS POUR LA ROULETTE DE MONTE CARLO (MONTE CARLO BOND) (1924): ART IS BUSINESS IS ART

Duchamp created his now-highly coveted "Monte Carlo bonds" to finance a system of wagering on roulette that he was developing in the famous casino town in Monaco. The bonds, issued in 30 shares at an assigned value of 500 francs each, were to be repayable to investors at the rate of 20 percent interest over three years—the selling point being that Duchamp claimed to have devised a proprietary system to reliably win at roulette. It might have been difficult to recognize this as an artistic gesture, except for the fact that the bonds prominently feature an image of Duchamp, taken by friend Man Ray, with his hair sculpted (using shaving foam) into what look like two horns on top of his head.

An ultimately unsuccessful business proposition (few people bought the bonds), Duchamp's Monte Carlo scheme also happened to be a prophetic art work, prefiguring the quasi-corporate aesthetics of artists like Carey Young, Michael Wang, or Brad Troemel, who have recenlty been making work about systems of currency and exhange. Wang, for instance, made a conceptual artwork out of buying a share of Procter & Gamble's stock, while Troemel has embedded Bitcoins within his vacuum-sealed object-paintings. In Duchamp's case, his collectors would have been wise to buy in: one of his Monte Carlo bonds sold at auction in 2010 for just over $1 million.

When Duchamp did stick to the more conventional two-dimensional approach to art making, he did it in the least conventional materials. Considered one of his finest works, The Large Glass is the subject of much conversation among art historians; it's been called "a tantalizing and ambiguous humorous depiction of the frustrated sexual desire between men and women," among other things. (It's components, including a "chocolate grinder" and a wasplike "bride" function as an elaborate and near-impenetrable erotic allegory.) It's also insanely fragile; now housed permanently at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, the work actually accidentally shattered into pieces before joining the institution's collection. It was later restored, and is now housed between two sheets of supporting glass.

Though he's known as a master conceptualist, the Large Glass displays Duchamp's interest in how material relationships follow conceptual ideas, an example that would be especially informative for the post-Minimalist artists of the 1970s—for example Eva Hesse and Bruce Nauman—when they reacted to Minimalism's austerity by using transparent, ephemeral, and organic materials.

ROTORELIEFS AND ANÉMIC CINÉMA (1935): ARTISTS' TOYS

The readymade is Duchamp's most potent contribution to art history, but much of his other artistic activity in the early 20th century was equally prescient, including his Rotoreliefs—abstractly painted disks meant to be played on a turntable like a record, transforming them into dizzying optical illusions. These works were first included in Anémic Cinéma, a 1926 film he made with Man Ray and Marc Allégret, in which the images of the six spinning designs of the Rotoreliefs are alternated with alliterative French puns. In 1935, the artist rented a tiny stand at the Paris inventors' fair, the Concours Lépine, to display and sell these pieces as "play toys," produced in an initial edition of 3,000. Though the Rotorelief excursion was a complete disaster from a financial point of view, Duchamp's experiment in the mass market is arguably one of the first instances of the "artists' multiple" before that idea was widespread. (It didn't come to full fruition until the 1960s.)

BOÎTE-EN-VALISE (BOX IN A VALISE) (1935-40): LESS IS MORE

Beginning in 1935, Duchamp spent five years meticulously recreating the major items of his artistic oeuvre in miniature, using photographs, hand-colored reproductions, and scale-down models of his sculptural works, which he enclosed in traveling cases in an edition of 300. While Duchamp had deliberately restricted his production of artworks over the preceding years—in proud counterpoint to the sprawling catalogues raisonné of certain Impressionist painters (Paul Cézanne produced over 900 paintings, excluding watercolors and incomplete works, over a period of 34 years)—his 'boxes,' including the Boîte-en-valise, drove the point home. They also provide a model for the artificially limited editions of theoretically unlimited works that have become a standard in the art market today; think of Wade Guyton's recent gesture of rebellion, when the high-selling artist recently attempted to subvert his own astronomical auction prices by simply printing out a bunch of copies of a previously limited-digital print.

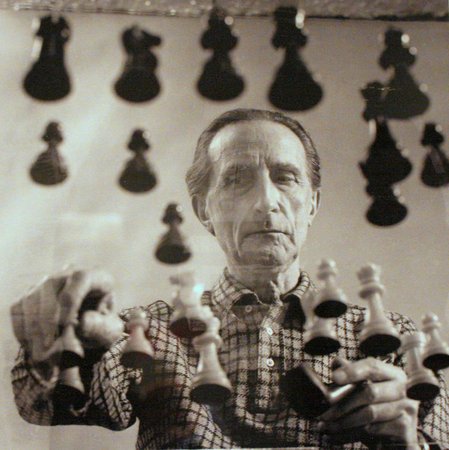

"CHESS PLAYERS ARE ARTISTS": EXIT THE ART WORLD...

Duchamp once famously said, "While all artists are not chess players, all chess players are artists." Duchamp was not only a proponent of the game, but also a major player: from 1918 through the rest of his life, he made serious contributions to the chess world, including working as a professional chess journalist. In fact, he told the world that he had entirely abandoned art to dedicate himself exclusively to the game—he was, as he put it, "a victim of chess." Many artists have quit making art in favor of other endeavors since: Charlotte Posenenske stopped making socially-inflected sculptures and, instead, became an actual sociologist in 1968, to give one famous example. In Duchamp's case, however, his retirement into chess was a ruse—an elaborate gambit that allowed him to "mate" the art community with the surprise revelation of his final masterpiece.

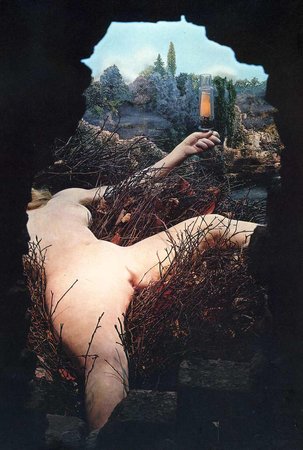

Long after Duchamp supposedly quit producing art in favor of chess, he surprised the world with his famous last work, which he made in secret over a 20-year period. Étant Donnés turns the artist's oeuvre on its head once again. The viewer approaches a heavy, anicent-looking wooden door; through a small opening at eye level, he or she peers inside to find a haunting and dreamily bucolic image: a naked woman lying in a pasture, holding a lamp aloft in one raised hand. The entire work is filled with jerry-rigged machinery, including a devise to make it appear as if a waterfall in the back of the diorama is constantly running. Duchamp maintained the mystery of the artist's production to the very end of his career, which falls on a plangent reminder of art's mysterious romance.