Since the Renaissance, when revolutionaries like Giotto and Brunelleschi used one-point perspective to illusionistically project the seen world onto the canvas, painting was traditionally devoted toward reproducing vision as it's captured by the human eye. The collective aim of the medium was to present scenes from life and history with total realism. Today, however, we take for granted that a canvas does not have faithfully reflect to be the way we see the world, and that a painting has its own internal rationality: a vocabulary of color, shape, and texture that provides a roadmap for the viewer's eye. In other words, the vision that the painter presents his or his work does not have to be a literal one—a leap forward for the potentialities of art. How did this remarkable shift occur?

In the early 20th century, encouraged by an aesthetic revisiting of what were then still considered "primitive" arts—most prominently those of Africa and Asia—and spurred on by rapid developments in photography in the late 19th century, which alleviated painting of its need to faithfully depict the natural world, European artists began experimenting with abstraction, shattering conventional notions of the function of artistic composition. The artists most closely associated with so-called Cubism's conception—the most radical single contribution to abstraction's development in Western Art—are Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque , who collaboratively (and secretively) developed the concepts behind the movement beginning in 1907. The images they concocted reflected a traumatized worldview, a novel form of consciousness torn asunder by technological and societal uphevals and then pieced back together.

Further innovations were soon contributed by artists like Juan Gris , Fernand Léger , Jean Metzinger , Robert Delaunay , and others. Under the purview of these avant-gardists, the canvas, rather than acting as an illusory window onto the world, became "the picture plane," tasked not with representing the world as our eyes see it, but instead with recalibrating vision for the purview of a radical modern culture. To provide insight into how cubism was born, and how it entered the art-historical bloodstream, we've assembled a gloss on the complex breakthrough below, which is indispensable for understanding today's art.

PROTO-CUBIST ABSTRACTION

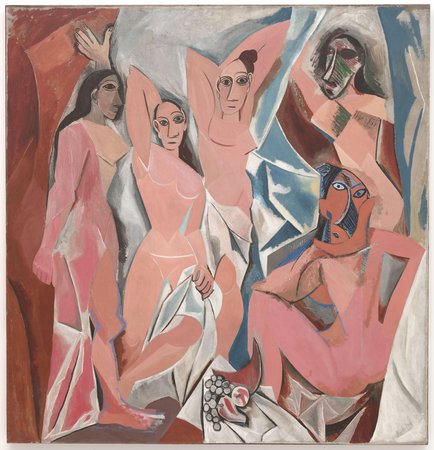

Pablo Picassos's

Les

Demoiselles d'Avignon

, 1907

Pablo Picassos's

Les

Demoiselles d'Avignon

, 1907

Many historians credit Picasso's Les Demoiselles d'Avignon as the foundational work of Cubism, and, thus, of all Modern art. Without going into the various interpretations of the characters depicted, and their faces—which look like African masks or Iberian busts—a quick look at the figure depicted second from the left reveals the reason that this painting is often called "proto-Cubist." The figure's top half makes her look as if she's standing, one arm raised above her head, and leaning against the curtained wall in the background. But her lower half sends a different pictorial message; her legs appear crossed, as if we were seeing her, lying on a bed, from above. This radical shift of perspective, showing two views of a scene at once, was unprecedented in painting at the time. The achievements of one-point perspective had been a drastic step forward in pictorial representation, and here was Picasso, undoing it all. Matisse called the work "the death of painting." And though Picassos' friend, Georges Braque, also intially hated the painting, at the same time, he couldn't stop thinking about it.

DU CUBISME

George Braque's

Violin and Pitcher

, 1910

George Braque's

Violin and Pitcher

, 1910

Picasso's

Demoiselles

sparked a very close and highly productive friendship between the Spaniard and Braque, which crystallized in the earliest properly Cubist works. Between 1907 and 1912—the period of so-called Analytic Cubism—the two artist's paintings became almost indistinguishable as they together developed a street-level color palette limited to off-whites, grays, browns, and blacks, and stark, angular forms that were meant to appeal to the viewer's intellect rather than their emotions, emulating the way images are formed in the brain rather than the eye and depicting multiple viewpoints at once. The pair eschewed beauty or idealized forms in favor of an entirely new investigate approach to their medium. It was what Metzinger referred to as a "total emancipation" ('affranchissement fondamentale') of painting.

Between 1913 and the 1920s, the initial developments of Analytic Cubism were expanded into what came to be called Synthetic Cubism, which emphasized the synthesis of the elements of the composition and introduced the idea of collaging elements onto the canvas—pieces of rope, cigar papers, and so on, as in Picasso's famous

Still Life With Chair Caning

, which employed a swatch of the titular material to depict a chair

—

and further breaking down the relationship between the surface of the painting and its subject matter.

CUBIC ODDITIES

Jean Metzigner's

The Bathers

, 1913

Jean Metzigner's

The Bathers

, 1913

It is important to note that Picasso and Braque did not name the movement they sparked themselves. The term "cubism" derives from critic

Louis Vauxcelles

's use of the term "bizarreries cubiques" ("cubic oddities") to describe paintings by Braque that were exhibited in Paris's

Salon des Indépendants

,

one of the city's major avant-garde annual exhibitions, in 1909. (The name of the preceding Fauvist movement had also derived from a disparaging remark by the same critic, who had pronounced Gauguin, van Gogh, and their ilk "wild beasts.") Two years later, the term had been widely adopted and used—disparagingly—by critics, who found the fledgling movement tasteless, vulgar, even immoral. This was in response to that year's Salon des Indépendants, where works by

Henri Le Fauconnier

,

Albert Gleizes

, Metzinger, Léger, and Delaunay, who had all absorbed and carried forward Picasso and Braque's aesthetic challenges, were on display.

From its entrance onto the global public stage, Cubism was a contentiously debated movement, and as such fully codified art's new function in Modern society: its tendencey to get people talking, the more heatedly the better. The work of Impressionist and Fauvist aritists in the preceding years had laid the groundwork for Cubism's radical development, but after Picasso and Braque's refinement of Modern painting's potential, and the extreme reactions it elicited from critics and the public, arts discourse would never be the same.

Cubism touched off the central debate in art of the 20th century: how the conditions specific to a medium could be refined, perfected, and best put to use by embracing a progressive, experimental, rationalist approach. Cubism's direct contribution to the art of the following century it is clear in Neoplasticism's geometry, the dynamism of Vorticism and Futurism, and Suprematism's fundamentalism, all further refinements based on painting as a way to shape and renew perception.

FROM ANALYSIS TO SYNTHESIS

Fernand Leger's

Staircase

, 1914

Fernand Leger's

Staircase

, 1914

Cubism, a revolt of the mind against decorative frivolity, left its major legacy in art history in the lasting idea that perception is a fluid, mutable thing that is not only governed by our biology or physiology, but can actually be created anew within , and then projected from, objects of art. As Cubism became synthetic, so too did its radical visuality synthesize with the pan-European aesthetics of Modernism, alongside the political, social, and cultural upheavels of the early 20th century.

The movement had radical implications not only for painting, but also for the poetry of Guillaume Appolinaire and Jean Cocteau , the literature of Gertrude Stein , and the music of Igor Stravinsky , all of whom applied the notion of shattered subjectivity, upturned tradition, and the refracted aesthetics into their respective mediums. By radically rethinking traditional ideas of representation, Cubism laid the groundwork for all art of the 20th century, including conceptual art, the foundation of all global contemporary art today. In many ways, we are still living in the Cubists' fragmented world.