“I came to New York to study art, and to meet artists. And where do you find artists? In bars,” James Rosenquist writes in his autobiography Painting Below Zero. And as any gallery-going vet knows, the art world and drinking go hand in hand. With the recent closing of the fabled Lower East Side establishment Max Fish—itself the brainchild of an artist, and a hangout for musicians and art-world denizens throughout the '90s—one might wonder what defines the “art bars” of then and now. In some cases it’s the clientele; in others it’s the art-historical cache. Here we take a look at a few of the classics.

THE CEDAR TAVERN

“I began hanging out at the Cedar Tavern, where I went with the sole purpose of meeting the grand masters of abstract expressionism,” writes Rosenquist. Perhaps one of the most famed “art bars” because of its connection to AbEx and New York School painters, Cedar Tavern used to be located at 24 University Place in the 1940s and early 1950s, then 82 University Place until it closed in 2006. “The Cedar was where Elaine de Kooning and Franz Kline knocked back a couple shots of scotch, sometimes accompanied by Frank O’Hara; where Elaine’s husband Bill once socked Clement Greenberg in the jaw,” writes David Lehman in The Last Avant-Garde. At its peak, the tavern also attracted the likes of Larry Rivers and Mark Rothko, and most notoriously Jackson Pollock, whose storied antics only added to the dingy dive’s allure, as described by Rosenquist: “The Cedar Tavern had been a workingman’s bar and therefore cheap. It was just a long, narrow space with a room in the back. It was where Pollock had kicked the bathroom door off its hinges and they left it that way.”

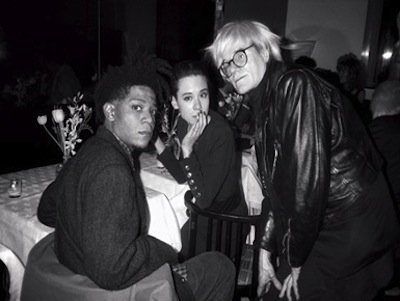

MR. CHOW

“As an artist's hangout, the elegant cream-lacquered interior of Mr. Chow's is light-years away from the Cedar Tavern, that grubby Greenwich Village haunt of the artists of the New York School 30 years ago,” declared a New York Times article from 1985, heralding in a new era of money-making overnight art sensations like Jean-Michel Basquiat, Keith Haring, and Kenny Scharf. Mr. Chow, the ritzy Chinese franchise, opened in Midtown New York on East 57th Street in 1978 and was a fixture for art-world denizens throughout the 1980s. Andy Warhol was a frequent visitor, and owner Michael Chow and his wife Tina established themselves as expert art collectors, purchasing many works from Basquiat, who became close friends with the couple. Tina passed away in 1992, but Mr. Chow himself remains very much a player in the art world, now on both coasts.

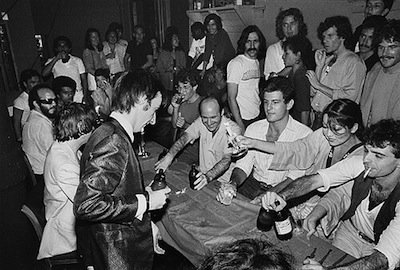

THE MUDD CLUB

The short-lived Mudd Club had a brief but memorable run, from 1978 to 1983 at 77 White Street. The avant-garde answer to the glitz of the Studio 54 set, it became a watering hole and performance space for the downtown arts scene. The space was in a loft owned by Ross Bleckner; an in-house gallery was curated by Haring; Warhol, Basquiat, and Glenn O’Brien could be found inside. “Why Are Lines Shorter for Gas Than the Mudd Club in New York? Because Every Night Is Odd There,” a headline in a 1979 issue of People reads.

CLUB 57

Club 57 in the East Village similarly had a brief run in the late '70s and early '80s. It opened in the basement of the Holy Cross Polish National Church on St. Mark's and hosted a mix of performance art and events like erotic Day-Glo art shows. The club was frequented by many from the same set as Mudd Club, like Scharf and Haring. The club is the topic of a 2009 book, Life As Art: The Club 57 Story, by its director, Stanley Strychacki.

BEMELMANS BAR

Less an art-world hangout than literal art bar: the Carlyle’s old-timey cocktail nook on the Upper East Side is well known for its namesake murals by Ludwig Bemelmans, author and illustrator of the beloved Madeline series. The prominent artist, who worked for Vogue and the New Yorker at the time, was commissioned to paint lighthearted scenes of Central Park for the hotel in the 1920s, when it was a residence for politicos, actors, and heiresses. Bemelmans famously did the work no charge—save for a year and a half of free rent for him and his family at the hotel. Today the bar remains a favorite of the art crowd, particularly the well-heeled types who frequent (and work at) Madison Avenue's chichi galleries, and downtowners when they venture to openings at the Whitney Museum.

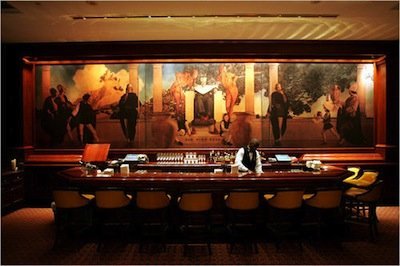

KING COLE BAR

King Cole also earns its place for its art-historical significance. It’s the site of a huge Maxfield Parrish mural titled Old King Cole, commissioned in 1906 for the Knickerbocker Hotel on 42nd Street. Parrish was a painter and illustrator with credits like The Arabian Nights to his name and created a huge, medieval-style tableaux to span across the bar. By 1932, the mural had ended up at the St. Regis Hotel, where it (and the namesake bar) resides today. The mural of the grimacing King Cole is also famed for a secret that “only the bartenders know,” according to the hotel's website, which is that the monarch has an impolite issue with indigestion. The painting may have gotten an amused rise out of Salvador Dalí's mustache—the artist lived in the hotel for years and frequented the luxurious bar.