In 1948 Edwin Land invented instant photography, a remarkable new process that allowed anyone to immediately develop and print photographs without a darkroom and using a single apparatus. His pioneering technology, developed for the Polaroid Corporation, became the company's prize product for the next 50 years. Early Polaroid advertisements marketed the novelty of instantaneity: “Just drop the film in your Polaroid ‘Picture-in-a-minute’ Camera and you're ready to shoot the best pictures you've ever taken." Millions of enthusiasts worldwide took the plunge.

By the early ’70s, artists working in a wide variety of mediums integrated the Polaroid’s snapshot aesthetic—shaped by its rigidly square format, inability to zoom (necessitating in-your-face photography), and tightly cropped result—into their own practices. World-renowned masters of the medium dabbled in its pleasures, like Walker Evans, who called it his "toy," and Ansel Adams, who snapped nature shots of Yosemite. Some younger artists even hacked the technology itself, such as Lucas Samaras, who manipulated the developing pigments to create skewed, devilish self-portraits.

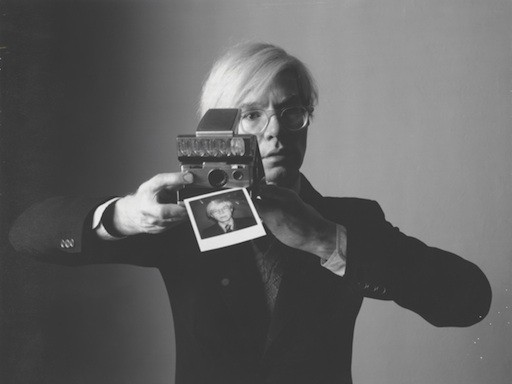

But it was Andy Warhol’s celebrity photographs and self-portraits, such as Andy Sneezing, that became some of the most celebrated—and coveted—examples of the Polaroid’s artistic use. Warhol also used the Polaroid Big Shot camera, a model developed primarily for portraiture, to shoot images that served as sources for his large-scale silkscreens. The Polaroid proved to be the perfect medium for Warhol’s Pop Art aesthetic. The instant, deskilled process removed the artist’s hand and epitomized Warhol’s imperative to break down the divide between high and low culture.

In a postmodern art world, the Polaroid proved to be an adroit medium for thinking through the construction of visual representation. In the 1980s and ‘90s, David Hockney, Bruce Nauman, and Robert Rauschenberg played with the Polaroid camera, using it to construct complex and distorted images. Hockney created large grids of photographs to produce warped, surreal versions of his usual portraits and pool scenes, as in Imogen + Hermiane Pembroke Studios, London 30th July 1982, using 63 Polaroid photographs. Rauschenberg employed bleach to wash out his large-format Polaroids in his Bleacher Series, which included works like Bleacher Series: Japanese Sky and Bleacher Series: North Carolina. Nauman’s Untitled (New Museum Image), meanwhile, uses a collage of Polaroids as the subject matter for a non-instant photograph.

In 2010 Sotheby’s had a hugely successful auction of instant-photography works from the Polaroid Corporation’s collection, exceeding the high estimate of $10.7 million with a $12.47 million sale of pieces by such artists as Warhol, Rauschenberg, and Chuck Close—an indication of how much the art world has recognized the high-art potential of the popular medium.

In 2008, the Polaroid Corporation went bankrupt for the second time in ten years and officially ended all production of instant photography products—leading to an outcry from artists and also from fashion designers, who traditionally have used the camera to chart their creative process. While their cessation of instant photo production seemed to signal the medium’s downfall, 2010 in fact turned out to be a big year for instant photography. A small group of Polaroid employees set out to save the iconic cameras, and by 2010 they launched the Impossible Project, an endeavor that claims to have “saved analog instant photography from extinction.” Currently, the Impossible Project is manufacturing instant film and cameras out of a factory in the Netherlands.

Today, artists still avidly use Polaroids in their work, as can be seen from Jeremy Kost’s campy collages of Hollywood types and drag queens. Despite the company’s bankruptcy and the advent of digital photography, it would seem that Polaroid has become an art world mainstay. Intriguingly, the simple analogue device also continues to have an outsize impact on the Web, inspiring the way images are engaged with on visual platforms from Instagram and Facebook to, yes, Artspace.

In this collection, we’ve assembled an overview of the diverse uses of instant photography by Artspace artists, from established powerhouses to emerging art-world newcomers.

An Instant History of the Polaroid