Appraising the value of fine art is usually a private matter, handled by experts behind closed doors and out of the public eye—and, as a result, there can seem to be a hazy veil of mystery surrounding it. The pricing of primary-market works is easy to understand, since they're set by the going rate that buyers are lining up to pay for a piece. But what about works, particularly historic works, that are so rare-to-market that guessing their value is beyond the ability of most mere mortals?

Lately, the possible sell-off of the Detroit Institute of Arts's collection as part of the city's bankruptcy proceedings has transformed this question into a pressing, headline-grabbing issue. Officials have retained Christie's to appraise the museum's multibillion-dollar Old Masters collection—a trove of masterpieces by Caravaggio, van Gogh, Bruegel, Vermeer, and other famous names, each of which could propel bidders into a record-breaking frenzy.

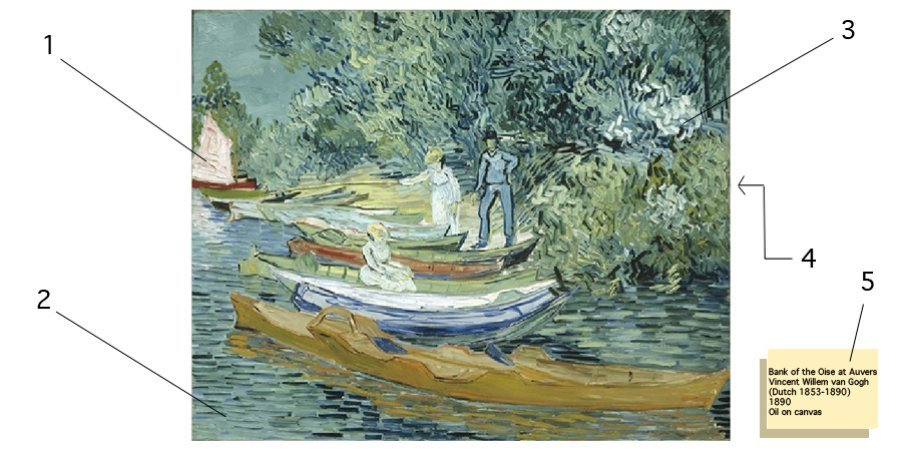

To better understand how appraisers can go about putting a price to such pieces, we asked Elizabeth von Habsburg, co-author of the new book Appraising Art: The Definitive Guide to Appraising the Fine and Decorative Arts, to break down the five basic steps one might take in evaluating the value of a work like Vincent van Gogh's lushly impressionistic Bank of the Oise at Auvers, currently part of the Detroit collection.

STEP NUMBER 1: The first step is to stand before the work and see if there are any tears or condition issues that can be seen with a naked eye. In areas painted with a heavy impasto, like on the sailboat pictured above, it might be possible to see cracks or flaking. Of the van Gogh, von Habsburg said, “This looks like it has a good surface, but you’d have to inspect it up close." There, an appraiser can use a black light to expose old cracks that have been “in-painted,” or filled in, by a restorer.

STEP NUMBER 2: Look for the signature. In this case, van Gogh did not leave his John Hancock, at least not on the front of the canvas. For some artists, that could raise an authentication issue, but this was not unusual for van Gogh, according to von Habsburg, who said that this detail would not affect the painting’s value.

STEP NUMBER 3: Compare the painting's style to the artist's signature works—which, if sold at auction recently, may offer market indicators. “This has everything you want in a van Gogh: lovely brushstrokes, strong colors, strong figures. The brushstrokes, especially, are what you want and here they are everywhere.” With van Gogh, however, it has been a long time since a painting of comparable quality has gone to auction—and his record, $82.5 million for Portrait of Dr. Gachet, was set all the way back in 1990. (Adjusted for inflation, that would be $150 million today.)

STEP NUMBER 4: Flip the canvas over. “The back often gives as much information as the front,” says von Habsburg. There you can spot collector labels (key indicators of its presence in historic collections) and stenciled auction numbers, plus patches, stitching, and other signs of repair.

STEP NUMBER 5: Look at the painting's provenance and exhibition history. “This one has a nice, clean provenance,” says von Habsburg, noting that, before making its way to Detroit, it was originally owned by the artist’s family and eventually landed at the then-prestigious Knoedler Gallery in New York during World War II—“you always want to look at the provenance during the war,” she added, to ensure that there are no restitution issues attached to the work.

So, how much is it worth? “Many, many millions of dollars,” is all that von Habsburg would venture, saying she couldn’t be more specific without conducting a complete, in-person appraisal. “I think you’d have no problem selling this on either the auction or private market. But that would be sad.”