Much of the art made today has some kind of digital component, but the movement known as net art—the Internet-based artwork created in the 1990s, the first decade or so of the World Wide Web— still looks radical. Taking to heart early net artist Heath Bunting 's credo “do something different,” net artists took advantage of suddenly ubiquitous personal computers and the first user-friendly web browsers to evoke a de-physicalized existence with infinite possibilities.

Building on other movements of the decade such as street art, relational aesthetics, and installation art, they made art even more accessible and participatory. Some of their efforts coalesced into broad movements like net.art and THE THING , loose, web-based communities of international “makers” who exchanged ideas and artworks online (generally without financial compensation or institutional support).

Two decades on, the art world is just starting to integrate these intangible and otherwise difficult-to-grasp pieces into the canon. Some have simply vanished, as the technologies they were based on have become obsolete, but many others have been preserved or upgraded for contemporary viewing. Below, Artspace has collected some of the most important net art works that remain available, based on Rachel Greene's excellent historical review Internet Art (Thames & Hudson, 2004). While perusing them, remember that you are experiencing these artworks in their “true” form and proper setting—no museum, gallery, or auction house required.

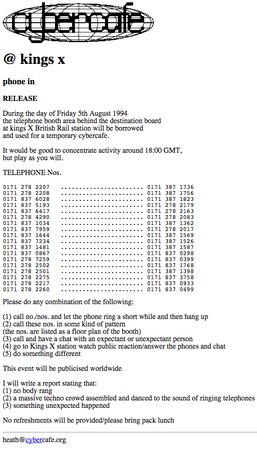

HEATH BUNTING

Kings Cross Phone-In

, 1994

Many of the early net artists were less concerned with making aesthetically-pleasing web pages than they were with harnessing and exploring the entirely novel power of the Internet, often in ways that extended far beyond their computer screens. British artist Heath Bunting ’s interventions often fall into this category. In 1994, he created a simple web page listing the phone numbers for all of the pay phones in London’s King’s Cross Station along with a date and time for people to call, thereby creating a proto-flash mob. His instructions were suggestively vague—he suggested that people “call and have a chat with an expectant or unexpectant person,” “answer the phones and chat,” or just “do something different.” The result was a cacophony of ringing phones and a series of chance encounters between participants and innocent commuters. In his recounting of the event (viewable here ), Bunting reports a strong turnout of “nerd, trendy, spy and anarcho double agents” as well as some very confused passers-by.

YAEL KANAREK

World of Awe

, 1995-present

The Israeli-American artist Yael Kanarek’s ongoing project World of Awe is a sprawling, variegated work, a fictional online diary that mixes love letters to cyborgs with 3D models and landscapes. Conceived as “a journal of a traveler in search of lost treasure,” in the artist's words, it's presented as a desktop interface with each “entry” in its own file. Her immersive project has delightful retro-futuristic touches; characters rediscover “the legendary Silicon Canyon” and muse about the fate of floppy disks. Updated over decades, World of Awe is an extremely dense work with layered links, pages upon pages of text, and fully tracked soundscapes. Rachel Greene compares this work to the Cremaster cycle, positioning Kanarek as a Matthew Barney of the Internet.

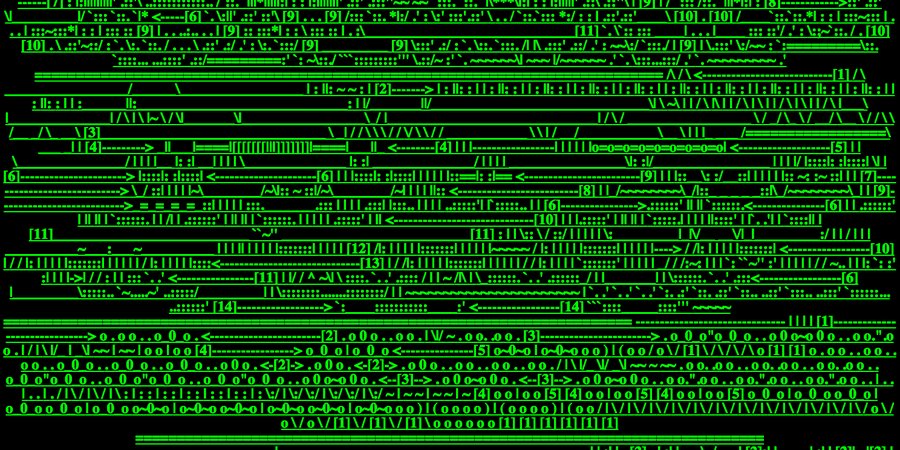

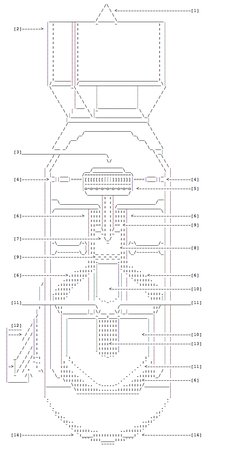

JODI.ORG

wwwwwwwww.jodi.org

, 1995

A collaborative art duo consisting of the Dutch artist Joan Heemskerk and the Belgian Dirk Paesmans , Jodi.org is responsible for many of the best-loved Internet artworks of the ‘90s— including most famously wwwwwwwww.jodi.org from 1995. An initial visit to the URL shows a page of nonsensical numbers, symbols, and letters, rendered in green on a black background that recalls the programmer’s terminal window. Viewing the webpage’s source info (right-click and select “View Page Source”) reveals the real "artwork": a series of digital “text-drawings” reminiscent of technical diagrams but made using the markup language HTML. Here, the hidden “instructions” are themselves the finished product—the alphanumeric hodge-podge one sees on the site’s front page is merely the incidental result of this coding.

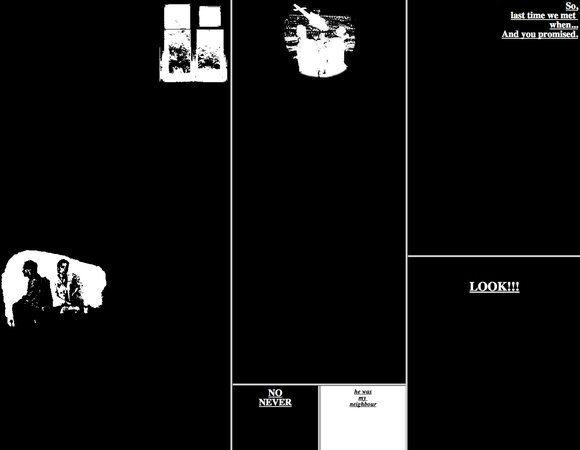

OLIA LIALINA

My Boyfriend Came Back From the War

, 1996

Many of the central figures in ‘90s Internet art (including Alexei Shulgin and Olia Lialina) hail from regions of the former U.S.S.R., where the rise of Internet access and the fall of the Soviet Union coincided almost perfectly and the freewheeling nature of early Web communities proved to be especially attractive to those who had been living under repressive regimes. Lialina’s 1996 piece My Boyfriend Came Back From the War is a browser-based, hyperlinked “netfilm” (to use her preferred term) that tells the fictional story of an unnamed beau returning from an unspecified conflict, with black and white images and simple bits of text. It moves away from the more technical considerations of net art to concentrate on narrative (however disjointed) and emotion, prefiguring the confessional mode of much digital art today.

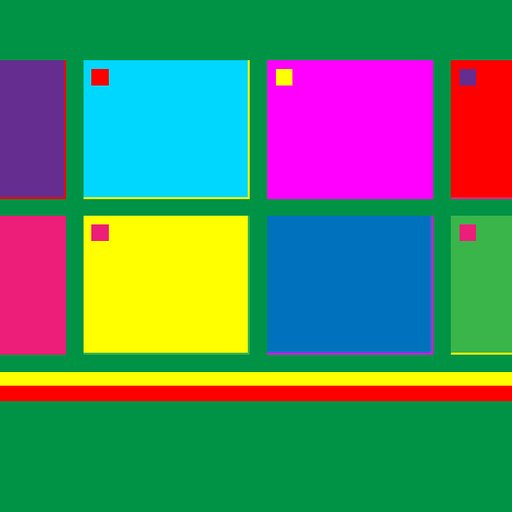

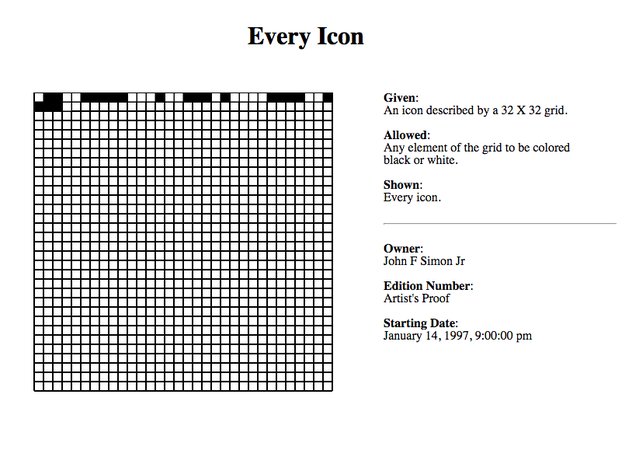

John F. Simon, Jr.

Every Icon

, 1997-present

Taking up the mathematical, process-based approach of predecessors like Sol LeWitt , and perhaps also the geometric purity of early-20th-century art movements like Suprematism , John F. Simon Jr.’s Every Icon from 1997 attempts to realize every pictorial icon possible in a 32-by-32 grid of black and white squares. A New York Times article published in 1997 calculated that, given then-current computing power, the work would take some several hundred trillion years to complete and would have 1.8 times 10 to the 308 th power possible iterations. These are numbers so large we lack the language to describe them—there’s little need to, even in the realms of advanced physics or cosmology. Every Icon is unique among early Internet artworks in that it allows for salable editions to be created, with each of the near-countless versions able to function as a unique artwork.

VUK COSIC

Deep ASCII

, 1998

Serbia's Vuk Cosic is best known for his use of the American Standard Code for Information Interchange (ASCII) coding scheme, which translates English letters and characters into binary integers (1010111, for example) for easy transfer between computers. Early Internet users quickly realized that images could be made with the same code using nothing more than a text editor, and Internet pornography was born. In a time before most browsers could load digital images, these text-images could be readily shared and viewed. Years after the crude format had gone out of style, Cosic co-opted the technique for his 1998 piece Deep ASCII , “translating” the entirety of the infamous 1972 pornographic film Deep Throat into ASCII. The result is a green-on-black composition of 1s and 0s that evokes a terminal window (for programmers) or 1999’s The Matrix (for the rest of us), viewable as a video or a single, massive text file.

YOUNG-HAE CHANG HEAVY INDUSTRIES

Various Works

, 1999-present

Originating in Seoul in 1999 with the meeting of the Korean artist Young-Hae Chang and the American poet Marc Voge , Young-Hae Chang Heavy Industries is remarkable among web artists and collectives for its commitment to a single format and process. Their artworks/poems (the artists have said they care little for the distinction) consist only of black text on a white background, with no hyperlinked navigation tools or any other interactive features. Instead, the text flashes in front of the viewer in a preprogrammed animation synced to jazz (often composed by the artists themselves.) Translated (and coded) into over a dozen languages, these humorous, often exuberant pieces anticipate the work of later Internet poets like Steve Roggenbuck . Their subjects include a reworking of Ezra Pound ’s Cantos , a description of the fictional Campbell’s Soup Town (where everything is made “of soup and for soup”), and more earnest calls for “love and brotherhood.”