What would American art museums look like if U.S. immigrants hadn’t contributed to them? We’ll find out tomorrow when the Davis Museum at Wellesley College removes all artwork made or donated by an immigrant—which for an encyclopedic academic museum like the Davis is roughly 20 percent of the permanent collection.

The gesture comes in support of a statement about the travel ban made by the American Association of Museums , which expresses a deep concern “that with the current executive order, artistic and scholarly collaborations could now be in jeopardy, just at the moment when cultural exchange and understanding are more important than ever.”

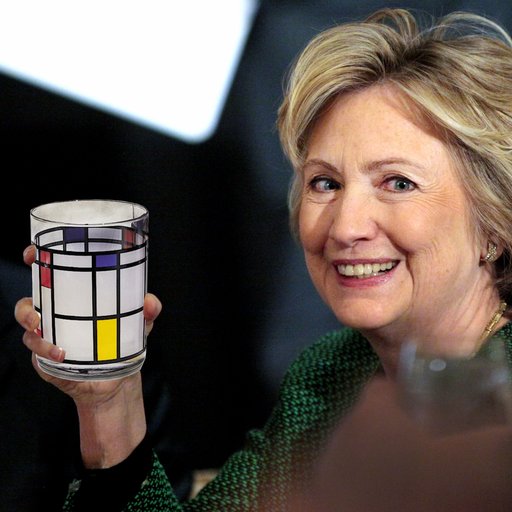

A de Kooning that will be removed from the Davis Museum's galleries tomorrow

A de Kooning that will be removed from the Davis Museum's galleries tomorrow

Roughly 120 artworks that had been on view at the women’s liberal arts college museum will be removed or covered tomorrow, including works by immigrant artists like

Willem de Kooning

(the Netherlands),

Hans Hofmann

(Germany),

Ana Mendieta

(Cuba),

Louise Nevelson

(Ukraine), and

Jules Olitski

(Ukraine).

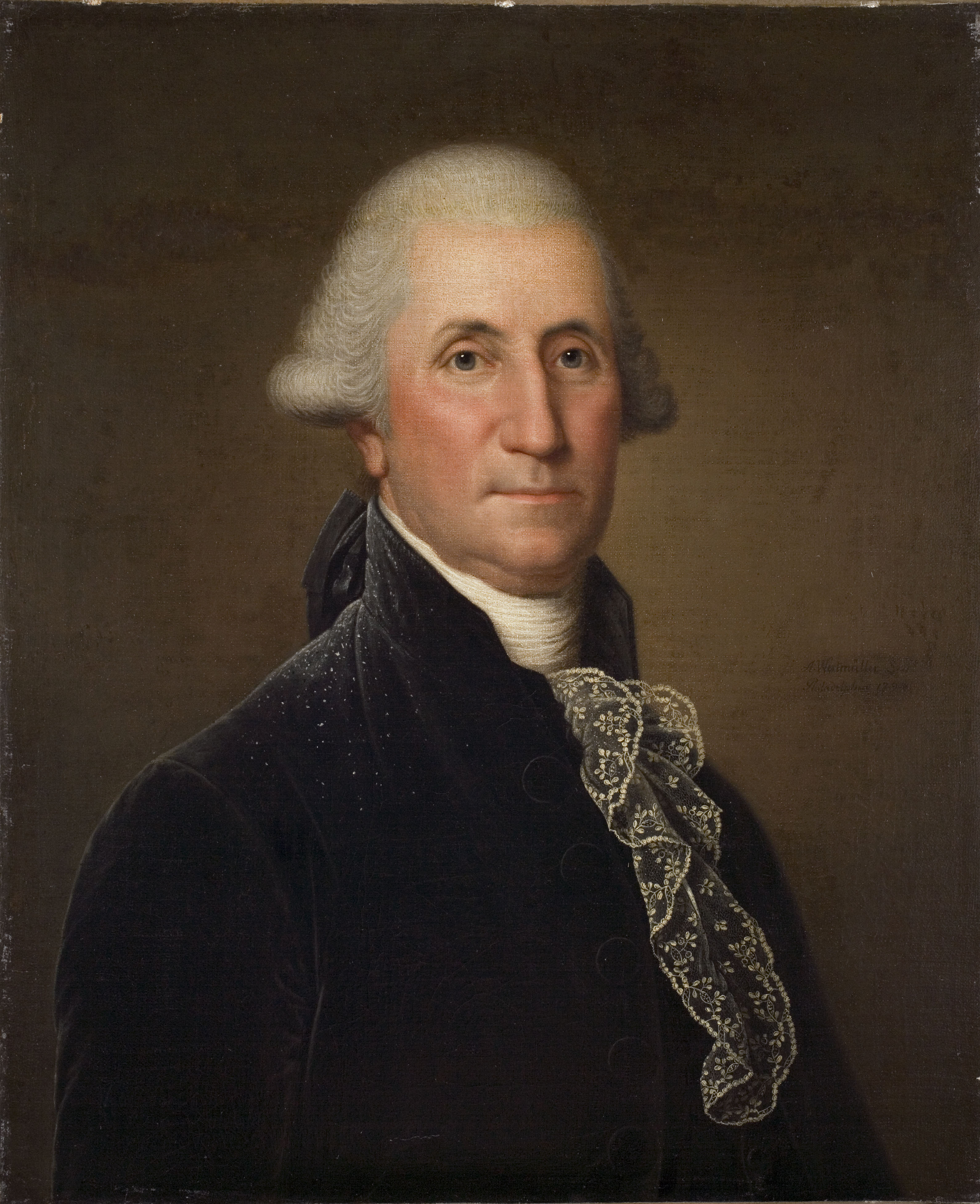

Ironically, Portrait of George Washington (1974-96) will be absent on President’s Day due to the fact that its painter, Adolf Ulrik Wertmüller , was born in Sweden and came to the United States in the 1970s. The oil painting was given to the Davis Museum by the Munn family, who emigrated to the U.S. from Sweden.

Portrait of George Washington painted by immigrant Adolf Ulrik Wertmüller

Portrait of George Washington painted by immigrant Adolf Ulrik Wertmüller

While paintings will be taken off the walls in the protest (which the museum is calling

Art-Less

)

,

objects displayed in vitrines will be covered in black cloth. The visual impact of this gesture will be most poignant in the African galleries, where nearly 80 percent of the works will be shrouded. The majority of African works were donated by the

Klejman

family, Polish immigrants who immigrated to the U.S. after World War II.

“ Art-Less demonstrates in stark and indisputable terms the impact of immigration on our collections,” said museum director Lisa Fischman , “and we proudly take the opportunity to signal that impact, to honor the gifts of creativity and generosity that make the Davis Museum and the Wellesley community great.”

The Trump administration has received an outcry of criticism and concern after announcing its plans to ban travellers from Muslim-majority countries as well as refugees, and many protesters have abstractly expressed how the absence of immigrants would be devastating. But the threat of this absence isn’t readily easy to visualize. With Art-Less, Fischman hopes “people will have poignant and meaningful experiences in the galleries as they confront the absence of immigrants, which speaks volumes. From that, one can extrapolate on the culture at large. It’s not abstract.”

The Massachusetts museum was well-poised to carryout the protest after having re-installed their permanent collection galleries in the Fall following a three-year research project involving objects that hadn’t previously been on view or that had rarely ever been seen. Fischman says she feels lucky to have been able to so easily pull up lists of immigrant artists and donors and to be able to “tell the story of collecting at Wellesley” while also “responding creatively to the ban, which is causing a lot of people reasonable anxiety and concern.”

Art-Less at the Davis Museum will be on view (or perhaps “off view”) from February 16 through February 21.