With its limited color palette (black and white, mostly) and narrowly defined subject matter (photographic portraits of “everyday” Muslims, often women), the Hirshhorn Museum ’s retrospective “ Shirin Neshat : Facing History” may initially conceal some of the subtleties of the Iranian artist’s work. But, as the show’s title suggests, Neshat's works are more than just documentation—they engage actively with the past, exploring and questioning the traditions (old as well as new) that have shaped Neshat’s life. There are no simple messages here; Neshat herself says that she works in “a place of only asking questions but never answering them."

The Book of Kings

installation shot

The Book of Kings

installation shot

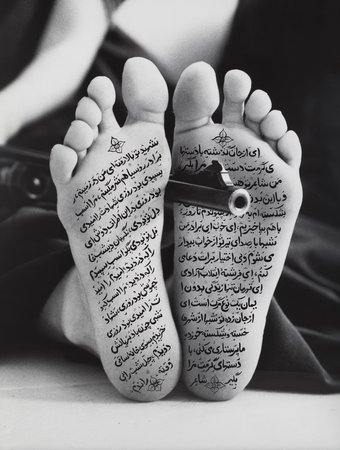

The survey incorporates art from the full span of Neshat’s career, including her The Book of Kings and Our House Is on Fire series from 2012-13, but it's anchored by her early body of work Women of Allah from 1993-97. These photographs are stylized portraits of Iranian women in chadors (the Iranian-style hijab), their skin covered in calligraphy; sometimes they are holding guns. Western viewers of this work can be forgiven for seeing it as an unambiguous critique of Islam’s treatment of women, but a more nuanced reading of the series reveals a different story—one of creativity, solidarity, and power within constraint.

The text on Neshat's subjects' skin is Persian poetry, an ancient and uniquely Iranian art form, and the guns they hold can be read as markers of the Iranian people’s revolutionary decision to fight for their own self-determination rather than languish under the United State’s puppet government. Even the hijab is more complex than it appears; the term translates to “partition” as well as “veil,” referring not only to the headscarf but also to the entire system of ritualized distance between men and women that underpins much of traditional Muslim culture. The chador is itself is a marker of Iranian modernity as well as tradition, as its usage became required post-revolution after nearly a half-century of being banned under the Shah. While the idea of a positive take on socially imposed gender disparity may upset Western sensibilities, Neshat’s work shows simplistic good/bad dichotomies on such complex issues to be misguided at best.

The text on Neshat's subjects' skin is Persian poetry, an ancient and uniquely Iranian art form, and the guns they hold can be read as markers of the Iranian people’s revolutionary decision to fight for their own self-determination rather than languish under the United State’s puppet government. Even the hijab is more complex than it appears; the term translates to “partition” as well as “veil,” referring not only to the headscarf but also to the entire system of ritualized distance between men and women that underpins much of traditional Muslim culture. The chador is itself is a marker of Iranian modernity as well as tradition, as its usage became required post-revolution after nearly a half-century of being banned under the Shah. While the idea of a positive take on socially imposed gender disparity may upset Western sensibilities, Neshat’s work shows simplistic good/bad dichotomies on such complex issues to be misguided at best.

The convoluted nature of hijab has proven fruitful for Neshat. Her films from the late ‘90s, including

Turbulent

(1998, see below) and

Rapture

(1999), again take up the separate sphere of womanhood as a site of both resistance and strength. These are staged interpretations of partitions, sometimes venturing into fantasy but always with a close eye for the aesthetic as well as social dimensions of the work. In

Turbulent

, for example, one screen shows a man reciting a classical poem to a packed (and entirely male) audience, while the other has a woman performing her own seemingly improvisational song to an empty room.

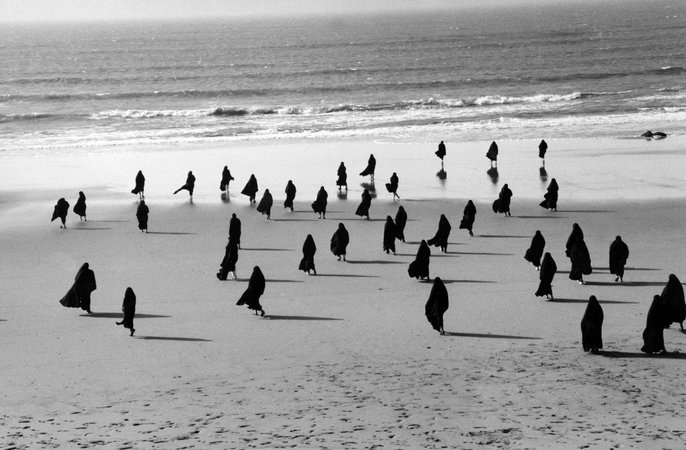

Rapture

follows two groups, divided by gender, as they cavort around a beach and a ruin. The piece ends with the women absconding to a boat, floating on to an unknown destination.

The convoluted nature of hijab has proven fruitful for Neshat. Her films from the late ‘90s, including

Turbulent

(1998, see below) and

Rapture

(1999), again take up the separate sphere of womanhood as a site of both resistance and strength. These are staged interpretations of partitions, sometimes venturing into fantasy but always with a close eye for the aesthetic as well as social dimensions of the work. In

Turbulent

, for example, one screen shows a man reciting a classical poem to a packed (and entirely male) audience, while the other has a woman performing her own seemingly improvisational song to an empty room.

Rapture

follows two groups, divided by gender, as they cavort around a beach and a ruin. The piece ends with the women absconding to a boat, floating on to an unknown destination.

Neshat’s films, like her photographs, are not merely critical of institutionalized divisions. Instead, they seek to explore these barriers as spaces for creative resistance. The two-channel installations make the split physical; each half is projected onto an opposite wall, forcing the viewer to choose. The whole picture cannot be viewed at once, a useful metaphor for Neshat’s work as a whole.

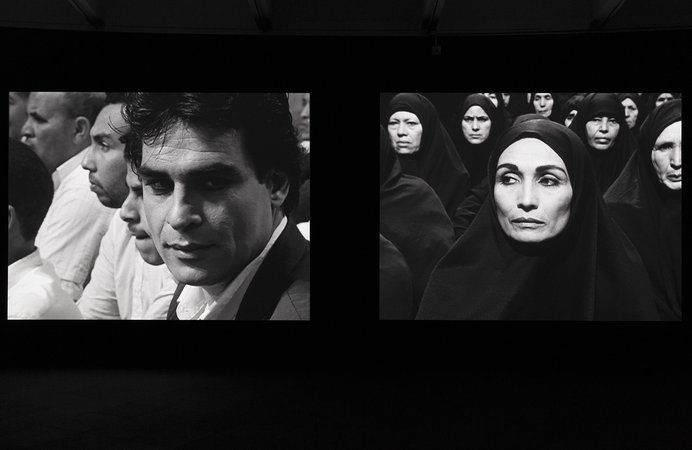

Still from

Rapture

, 1999

Still from

Rapture

, 1999

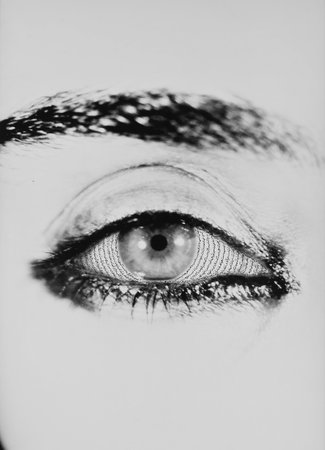

Offered Eyes

, from the series

Women of Allah

Offered Eyes

, from the series

Women of Allah

Our House Is on Fire

, installation shot

Our House Is on Fire

, installation shot

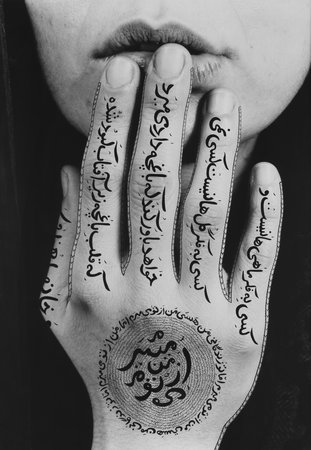

Untitled

, from the series

Women of Allah

Untitled

, from the series

Women of Allah

Still from

Fervor

, 2000

Still from

Fervor

, 2000

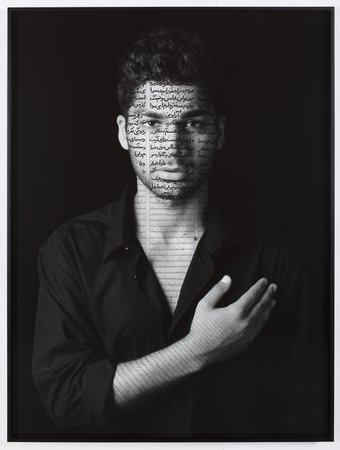

Muhammad

, from the series

The Book of Kings

Muhammad

, from the series

The Book of Kings