Animation is more visible and ubiquitous than ever, thanks to the wide availability of digital modeling tools like Maya and Blender and the spread of video game aesthetics into the wider culture. Computer programs have taken much of the hard manual labor out of animation; the days of painstakingly drawing each and every frame are behind us.

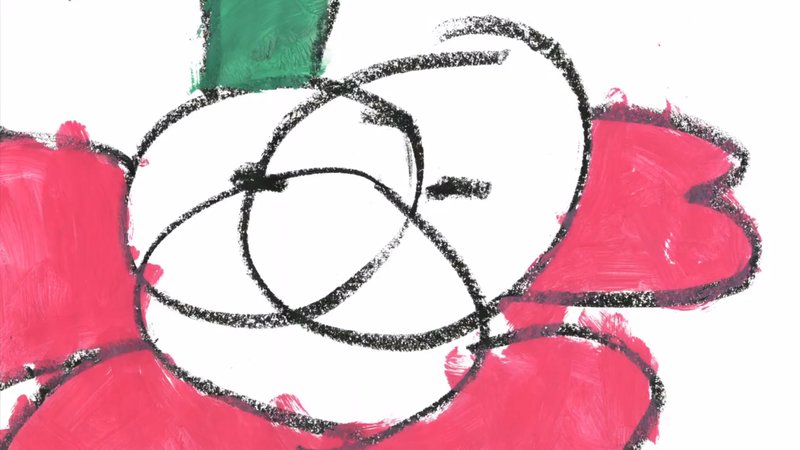

Still from

Fruit Fruit

, 2013

Still from

Fruit Fruit

, 2013

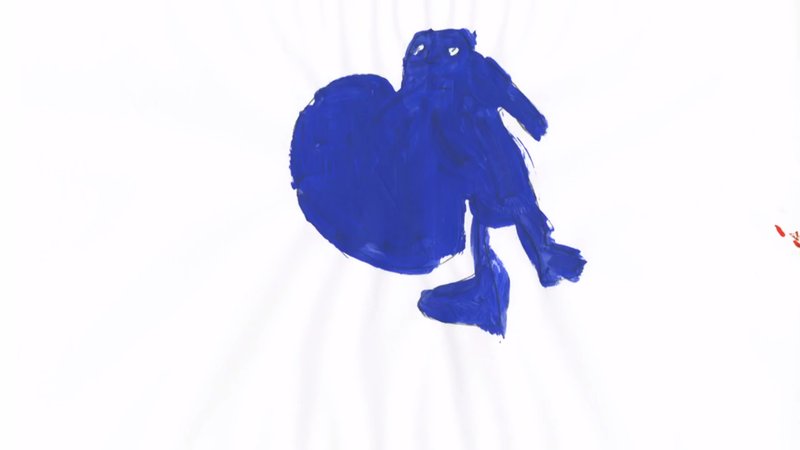

Quietly bucking this trend is the British artist Peter Millard , who hand-draws all of his wonderful, bizarre animated shorts. His films have a distinctive style that borders on the childlike, with a dramatically simplified color scheme and a rough, color-outside-the-lines approach that doesn’t shy away from dramatic shifts and spurts of action. Using oil pastels and paint to render his figures (anthropomorphized bananas and warping androgynes are favorites), Miller embraces the chance errors that inevitably arise in the highly repetitive animating process. The results are figures that reveal glints of brushstrokes as they move through the frames, looking very much like impressionistic doodles brought to life.

Color changes are frequent, as are explosions in which figures burst only to be quickly reconstituted. The animator draws inspiration from jazz virtuosos like Charles Mingus and the recently-deceased Ornette Coleman to help keep his drawings loose and unfussy, and this freewheeling approach shines through in each of his shorts. These soundtracks also include samples of jazz and, often, noises generated by Millard himself.

Still from

Bomb

, 2014

Still from

Bomb

, 2014

Long seen as a bedroom auteur, Millard is finally getting some real recognition for his 2013 piece Fruit Fruit; it won him a residency at the Viennese “ art and culture complex ” MuseumsQuartier Wien after being screened at this year’s Vienna Independent Shorts Film Festival. The film shows Millard at his best and most abstract; clocking in at just over two minutes, it's an action-packed ride through color and sound in which apples, bananas, strawberries, lemons, and what appears to be a pineapple are squashed, pulled apart, dematerialized, and made to talk.

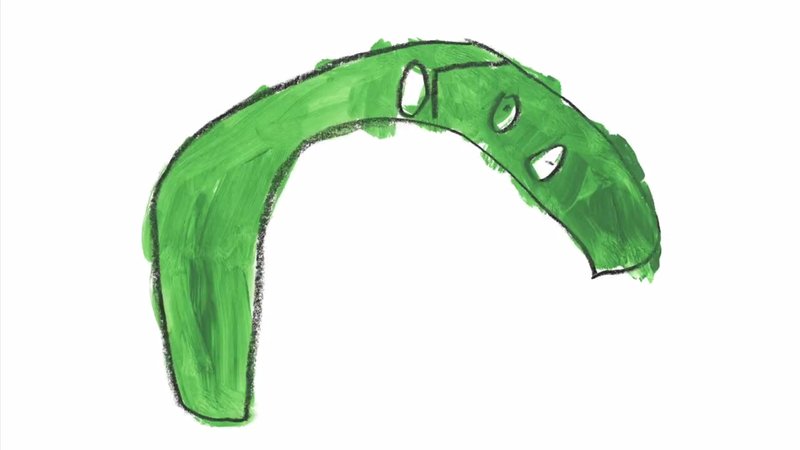

In one segment a cartoon-faced strawberry yawns (or maybe screams) until its sides burst and its eyes grow beyond the point of cohesion. The berry is in good company here; the various fruits cannot seem to keep themselves together even when they’re not being actively stepped on, a recurring mishap that becomes a beat of sorts for the film. As in Millard's other works, the sound here does as much as the drawings; noises like the cucumber’s pseudo-mechanical hum and the altered human voice “narrating” the piece become as jarring as the images onscreen. This is a sensory onslaught in the tradition of classic animation.

Still from

Fruit Fruit

, 2013

Still from

Fruit Fruit

, 2013

The climax of the piece occurs around the 1:40 mark, where the flashing colors are finally, almost blissfully replaced by a still of Millard’s rough-hewn (and faceless) lemon, as a low, droning tone plays in the background. The scene holds for a full 15 seconds (an eternity in a film this brief) before flashing to rapid-fire photographs of real fruit. In a piece that refuses to shy away from excess in color and sound, the still lemon seems an important counterweight, a reminder of the humble, difficult, and physical origins of animation.