The period between 1960 and 1985 in Latin America was definitely radical, to put it mildly. Distinct in its political tumult, the era is marked by nationalistic isolation, totalitarian dictatorships, guerrilla insurgencies, and the spirit of revolution. Resisting the forces of political and social oppression were Latina women artists, eager to imagine and forge new and radical futures for themselves and all others.

Predominantly omitted from the mainstream cultural discourse of their time (for the most part, Latin American art was ruled by painting that, in turn, was ruled by men), these women were also frequently alienated from the rhetoric of leftist political movements. In an L.A. Times article, Mexican artist Ana Victoria Jiménez reflects on a popular Mexican revolutionary hymn that went, “A parir madres Latinas, a parir mas guerrilleros” (Latin American mothers, time to give birth, to birth more guerrilla fighters). “It used to make my hair stand on end" said Jiménez. "You are fighting for independence, for the liberation of women, for a dignified life—and someone comes along to tell us that if we’re not good at making babies, then we don’t count.”

“Radical Women: Latin American Art, 1960-1985” at the Hammer Museum seeks to consider the works of these pioneering women on their own terms. As part of “Pacific Standard Time: LA/LA”, an ambitious exploration of Latin American and Latino Art in dialogue with Los Angeles that spans across more than 70 cultural institutions throughout Southern California, this groundbreaking exhibition will address an art historical vacuum that has omitted these women from the international record, reappraising their contributions to global contemporary art. The touring exhibition features 116 artists representing 15 countries and will be at the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles from September 15th through December 31st. From there, it will travel to the Brooklyn Museum in New York to be on view from April 13th to July 22nd of next year.

To celebrate this momentous exhibition, we are featuring nine out of the 116 radical and downright badass Latinas on exhibition at "Radical Women." So read on, get to the show, and remember, “sin mujeres, no hay revolución”.

MARTA MINUJÍN

Argentina

For the Buenos Aires-born pop and performance artist Marta Minujín , “everything is art.” Given the sentiment, it comes as no surprise that during a 1966 Guggenheim Fellowship residency in New York, she became very close friends with none other than Andy “everything is beautiful” Warhol. The two would go on to collaborate on one of her most famous "happening" works titled The Debt (1985) in which, as a response to the Latin American debt crisis, Minujín purchased a shipment of maize and had photos taken of her handing it to Warhol as a symbolic "payment" for the debt. A pioneer of happenings (performances that actively engage the viewer as a participant), Minujín’s distrust for the collectible art object also led her to pursue and pioneer other forms of ephemeral art like performance, sculpture, and video, often with a political bent. Following the return of democracy to Argentina in 1983, Minujín created Parthenon of Books, a colossal monument celebrating freedom of expression—a right that had been suppressed during the previous seven years of military dictatorship. The artist amassed 30,000 books that were banned during the dictatorship and installed them in the shape of the Parthenon along the Ninth of July Avenue in Buenos Aires. After three weeks, this enormous library of newly liberated titles was dismantled and distributed to the public.

ANALÍVIA CORDEIRO

Brazil

The São Paulo-based performance artist, dancer, and choreographer is widely recognized as being the creator of the very first video artwork in Brazil with her 1973 piece,

M3x3

. Not only was this pioneering work revolutionary in its video format, it also is the very first computer dance. Using experimental computer software developed in collaboration with Brazilian pop artist Nilton Lobo, the program enabled an image-capture system that codified dancers' movements, allowing the system to manipulate its sequences into new gestures, compositions, and choreographies. This system became a vital precursor to the kind of motion-capture technology we see so widely used in special effects today.

PAZ ERRÁZURIZ

Chile

Chile under the Pinochet dictatorship was, to say the least, not a terribly friendly or tolerant place. In 2011, a Chilean human rights commission identified over 40,000 victims of political violence during that time period that were tortured or exiled (over 3,000 of them were killed.) In a regime infamous for Pinochet’s Caravan of Death (also known as the Chilean Army Death Squad), voicing the lives of the oppressed required extraordinary courage and compassion. In the midst of all this terror, photographer

Paz Errázuriz

turned her gaze toward the most vulnerable and marginalized in society, documenting their existence and giving them voice, power, and the ability to be seen. In one of her most important series,

La Manzana de Adán (Adam’s Apple)

(1983), she documents the lives of Mercedes, Evelyn, and Pilar, three transvestites working in the brothels of Talca and Santiago.

MARIA EVELIA MARMOLEJO

Colombia

If you think Marina Abromovic is intense, you should meet Maria Marmolejo. Considered one of the most radical and political artists of 1980s Latin America, her performances and installations are unflinching confrontations of political violence. In her earliest performance piece, Marmolejo paid homage to the tortured and disappeared of the oppressive Ayala regime by walking silently over white paper while dressed in a white tunic and cap, her face covered in bandages denoting anonymity. Taking a seat, Marmolejo proceeded to make cuts under her toes, then continued to walk, leaving a trail of blood behind her. In the second part of the performance, the artist treated her wounds and continued to walk on bandaged feet. Her work sought to bring to light the daily violence in Colombia as well as the need to heal.

MARGARITA AZURDIA

Guatemala

Margarita Azurdia is also known as Margot Fanjul, a.k.a. Margarita Rita Rica Dinamita, a.k.a. Anastasia Margarita. However you’d like to address her, the Guatemalan artist was a creative force in all her iterations. An active feminist, Azurdia worked as a sculptor, painter, poet, and performance artist, creating works that put women at the helm of anti-establishment subversion. Her magical realist work in sculpture often involves colorful, fantastical figurations of women carrying firearms, babies riding on crocodiles, and tigers transporting bananas, all adorned in ornamental skulls, masks, and feathers. Crafted to her specifications by local artisans, her works use traditional folk art practices in order to create sacramental objects for a new future. Azurdia also founded a new art movement in the ‘60s known as new conceptual abstraction in opposition to the male-run Grupo Vertebra that championed neofigurativism.

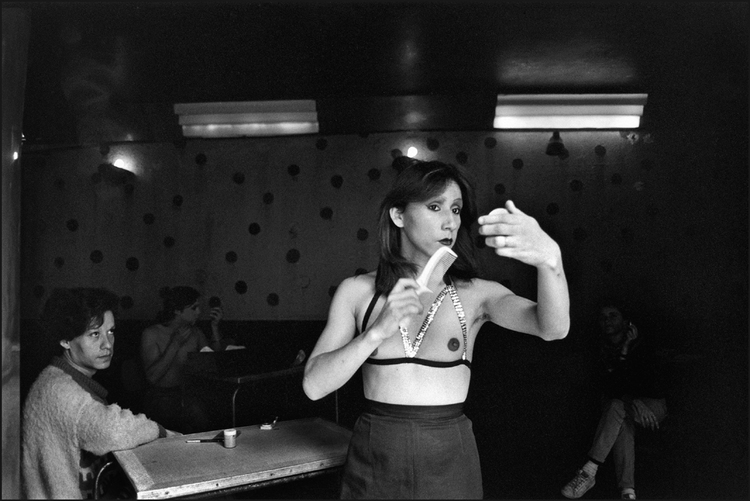

POLVO DE GALLINA NEGRA

Mexico

Founded in by Mexican artists Maris Bustamante and Mónica Mayer in 1983, Polvo de Gallina Negra was the country's first feminist art collective. (Translated in English, Polvo de Gallina Negra means Black Hen Powder, which the artists have said is used "to protect us from the patriarchal magic which makes women disappear.") Using humor combined with radical social criticism, the collective’s activities included demonstrations, exhibitions, conferences, publications, performances, curatorship, and mail art over the course of ten years. “We grew while we built our families,” wrote Bustamante, “so we had a lot of fun discovering that the social and cultural reality is penetrable.” In 1987, the group persuaded a popular news anchor to dress up as a pregnant women and be a

Mother for a Da

y on a television show while he and the Gallinas discussed motherhood and female archetypes.

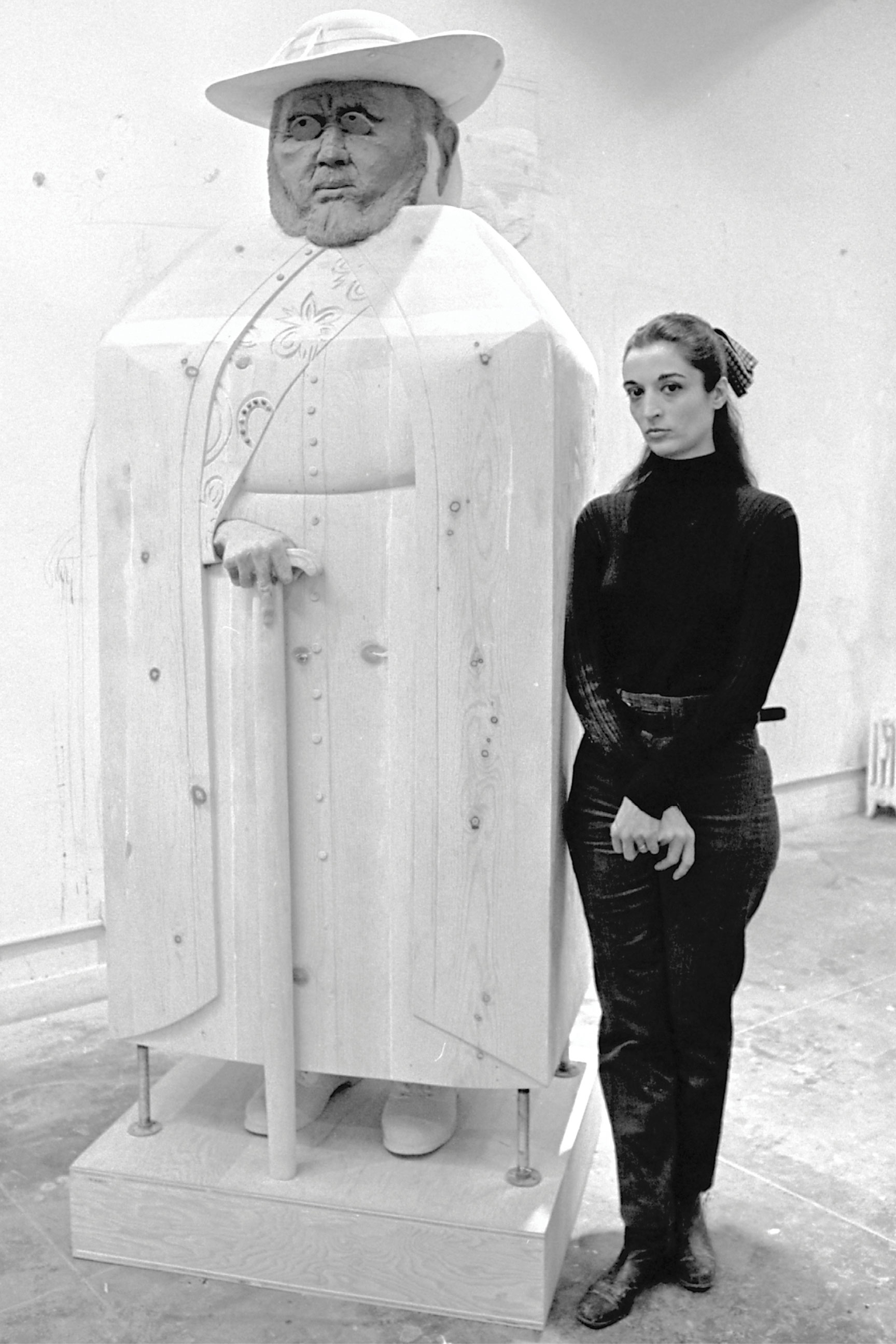

TERESA BURGA

Peru

In a 2011 Frieze review of Teresa Burga's survey at Württembergischer Kunstvereina, art historian Jörg Scheller wrote, “her conceptual art came across as so smart and so nonchalant that one was tempted to coin a neologism: nonceptual art.” As the only woman in Peru’s Arte Nuevo group, Burga had a voice that was distinct in a movement that is widely credited with introducing new avant-garde concepts to Peru—movements such as Pop art, Op art , and happenings. In one of her major works, titled Perfil de la mujer peruana (Profile of the Peruvian Woman) (1980-81), Burga collaborated with psychologist Marie-France Cathelat to investigate and analyze the status of working women in Peru. The study took into account their affective, psychological, sexual, social, educational, cultural, linguistic, religious, professional, economic, political, and legal characteristics in order to inform a series of colorful diagrams and visualizations. In that same survey review, Scheller writes, “Burga never celebrated Conceptual art as bloodless asceticism.”

JUDY BACA

Los Estados Unidos

If you’re local to Los Angeles, chances are you’ve seen Chicana artist Judy Baca’s work. As the co-founder and director of the Social and Public Art Resource Center, Baca designed the

Great Wall of Los Angeles

, completed in 1984. Executed by 400 community youth and artists coordinated by SPARC, the mural depicts the history of California “as seen through the eyes of women and minorities,” and at 13 by 2,754 feet, it's one of the largest murals in the world. Initially a high school teacher, Baca discovered art making as a tool for collaboration amongst students who “were not very friendly with each other.” This discovery moved her to bring this practice to rival gang members in Boyle Heights, Los Angeles. In the summer of 1970, a group of twenty members from four different gangs decided on a name for their mural—

Las Vistas Nuevas

(New Views). In Baca’s words, “I want to use public space to create a public voice for, and a public consciousness about people who are, in fact, the majority of the population but who are not represented in any visual way.”

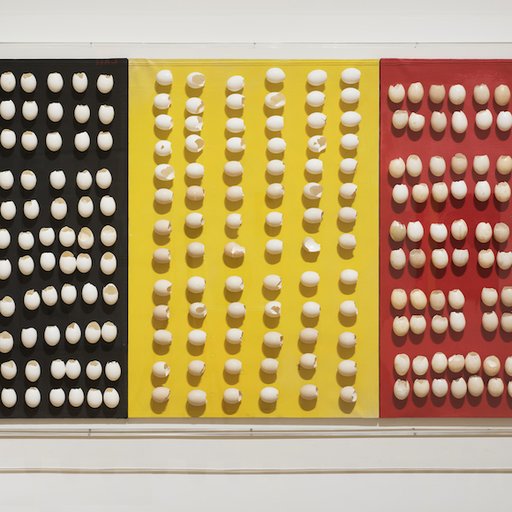

MARISOL

Venezuela

“It started as a kind of rebellion," explains Marisol Escobar (typically known simply as Marisol.) "Everything was so serious. I was very sad myself and the people I met were so depressing. I started doing something funny so that I would become happier—and it worked.” Inspired by pre-Columbian art, Marisol's wonderfully crafted, totemic wooden sculptures are evocative of folk art traditions, but their remarkable pop sensibility made them hugely successful in the 1960s New York art scene. In her heyday, she was heralded in Life magazine’s 1962 “Red-Hot Hundred” list and according to The Boston Globe , 3,000 people waited in line to see her 1966 show at Sidney Janis Gallery. The artist's booming success and celebrity (another friend of Andy Warhol’s, Marisol was featured in several of his films) eventually waned however, almost obscuring her to the point of omission. This had to do with several factors, but the main reason was simply that the folksy, figurative art was just not in style anymore. Conceptualism and Minimalism were the new en vogue in art, and Marisol’s works were considered too sentimental. It wasn’t until 2014 that the artist made a comeback when curator Marina Pacini organized a retrospective at the Memphis Brooks Museum of Art, stating that her aim was “to return [Marisol] to the prominence she so rightly deserves... Her works remain as important today as they were when she made them.”

RELATED ARTICLES:

Art Vs Trump: 40 Creative Acts of Resistance Since Inauguration Day

Make America Mexico Again: 10 Artworks About Immigration and the Border