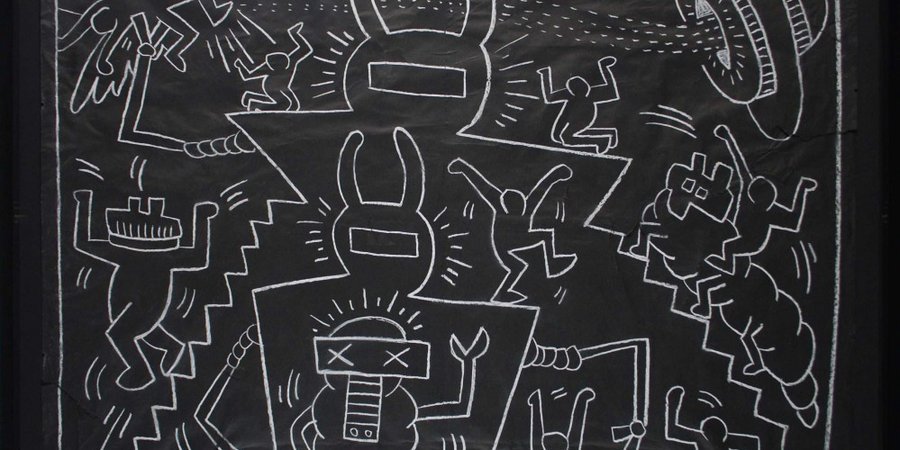

In 1984, no one could escape graffiti in New York—that summer, over 90 percent of subway car interiors had been covered with it. Beginning in the 1960s, graffiti increasingly cropped up in the city, and by the '80s it was everywhere. “Actually, the new graffiti was everywhere except the art world itself,” Jeffrey Deitch wrote in the original 1984 catalog for “Calligraffiti,” the landmark show he co-curated with gallerist Leila Heller .

Tee Bee's

Untitled

(1984)

Deitch and Heller came up with the original idea while Deitch was head of the art advisory division at Citibank. He had just sold his Chinatown apartment and, while he was moving, was staying in a one-bedroom apartment behind Heller’s gallery. Deitch began to connect the dots between his interest in graffiti and the Iranian artists Heller was working with at the time, who used script and calligraphy in more modernized, abstracted ways.

“We’ll make your gallery look like the inside of a Trans-Atlantic subway car,” he told her. The show included over one hundred artists: graffiti stars like Keith Haring alongside Middle Eastern artists such as Massoud Arabshani, as well as contemporary artists who pioneered gestural abstraction, like Jackson Pollock.

Jackson Pollock's

Untitled 1,

(1951)

Now, 30 years later, graffiti may not be as much a part of New York City streets, but it’s found in art galleries the world over, including the Middle East, where artists increasingly use it to engage with the political issues of the day. Deitch and Heller both agreed the show was in strong need of an update on the eve of its anniversary, hence “Calligraffiti 1984/2013,” running from Sept. 5 to Oct. 5 at Leila Heller Gallery.

“I always knew I wanted to revisit Calligraffiti,” Heller told Artspace. “Every time I came across these new artists, I would immediately think, if they had been around in 1984 I absolutely would have had to include them in the show. It was all of those moments that pushed me to recreate the show and bring it up to date.”

Such additions include the French Tunisian artist El Seed, with his boldly colored acrylic on canvas works, at once evocative of Arabic script and graffiti tags.

El Seed's

In the desert of language, calligraphy is the shade where I rest

(2013) (Courtesy Ouahid Berrehouma / itinerrance GALLERY)

Less obvious perhaps is work by Shirazeh Houshiary, with her dreamy works on paper defined by bold yellow symbols, or Shirin Neshat’s C-prints of faces faintly covered in calligraphic script.

Shirin Neshat's

Zahra

(2008)

Art and graffiti stars of the 1980s like LA2 and Kenny Scharf have new work in the show as well.

LA2's

LA's Lil' White Violin

(2013)

Many of the updates were spurred by the likewise updated technology and modes of sharing graffiti and art from the Middle East, and Heller says many of the works in the show were found using digital research.

And whereas 30 years ago New York graffiti artists communicated with one another using subway cars as their billboards, now “technology and the Internet—really all social media—has made it possible for collectors and artists to be aware all the new graffiti artists that have emerged in Cairo during the Arab Spring, China, Iran, and all over the world,” Heller says.

In a riff on that idea, graffiti-artist RETNA's image of a tagged, abandoned plane is in the show. Ever more modern, El Seed appeared at the opening to paint a mural in the 11th Avenue windows, and LA2 tagged the clothes of gallery staff. Later in the month, Julien Breton will do a light graffiti performance on the gallery building itself. Graffiti will be inescapable again, at least for a while in Chelsea.