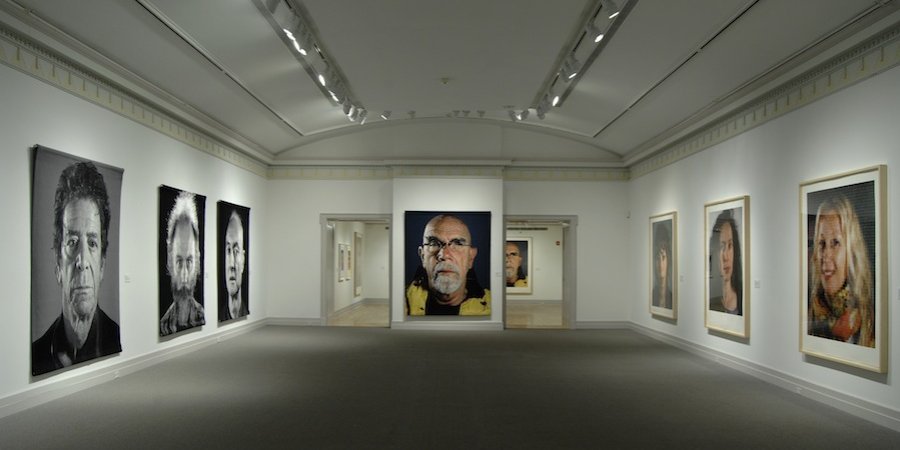

Chuck Close is one of those artists whose tremendous renown—he's one of the most famous living artists—and instantly recognizable style can, ironically, be a hurdle for appreciating the true depth of his work. This fact comes across clearly in the artist's new show at East Hampton's Guild Hall, which is essentially a miniature survey of his work from the last decade, applying his brand of portraiture to a diverse set of mediums. It's a stunning, and surprising, show.

The key thing to know about Close's art is that he suffers from prosopagnosia, a condition that makes facial recognition all but impossible; every time a person, no matter how beloved, so much as tilts their head, they seem to morph into a completely different, indecipherable stranger. For this reason, Close has devoted himself to photographing the people closest to him—and in this show those people are largely famous artists, including Cindy Sherman, Lou Reed, Joel Shapiro, Kiki Smith, and Cecily Brown—and painstakingly committing their faces to a surface in an attempt to become intimately familiar with their appearances.

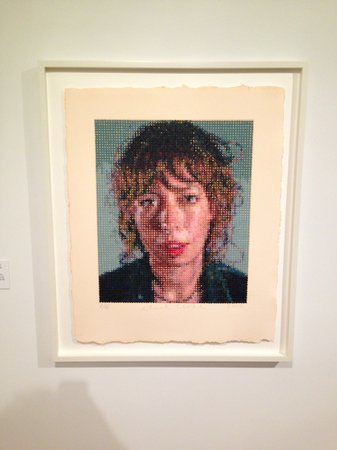

A 2012 portrait of the artist Cecily Brown, made by using a felt hand stamp to apply oil paint to silk

A 2012 portrait of the artist Cecily Brown, made by using a felt hand stamp to apply oil paint to silk

Over the years, these surfaces have changed, from canvases that he divides into grids to simplify the enlargement of the photo and add a note of painterly abstraction, to exquisitely rendered works on paper (including works, featured in this show, made by using felt hand stamps to apply oil paints to a piece of silk-screened paper), and now to jacquard tapestries. These last works are remarkable: standing nearly eight feet tall, they're composed of colored threads that catch the light in extraordinarily vivid ways, giving them an almost holographic sense of depth and volume.

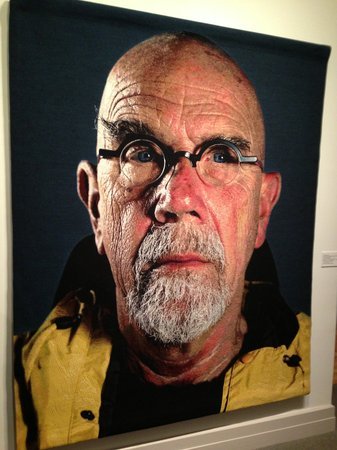

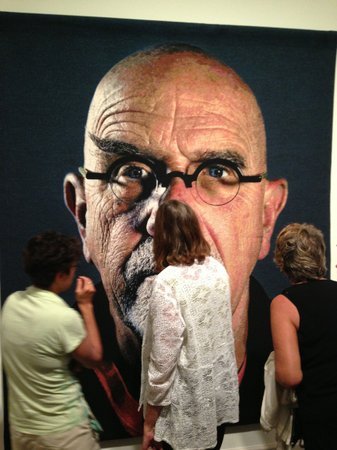

A 2013 Jacquard tapestry self-portrait

A 2013 Jacquard tapestry self-portrait

The black-and-white pieces are particularly absorbing, since to make the white pop Close wraps each thread with multiple strands of differently toned white yarn, making the color physically stand out from the composition for a brightly effulgent effect.

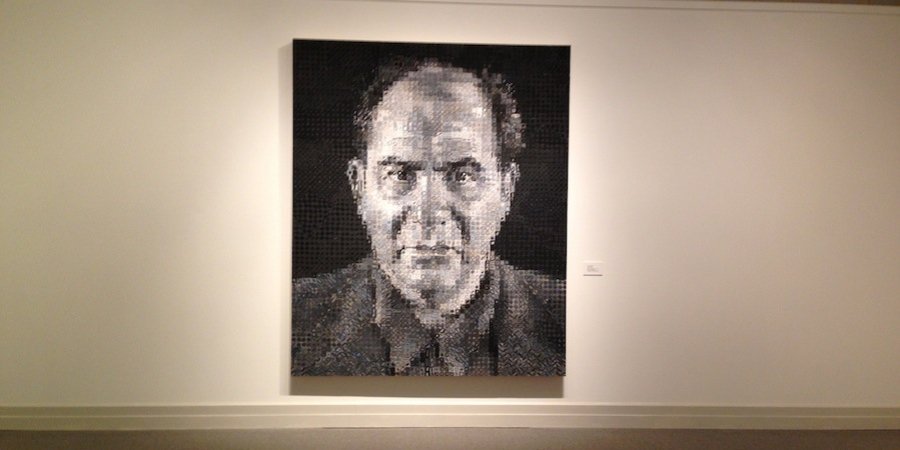

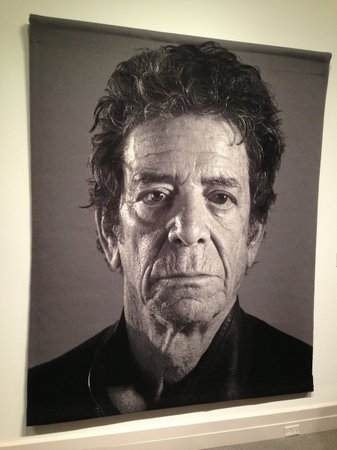

A 2013 Jacquard tapestry portrait of Lou Reed

A 2013 Jacquard tapestry portrait of Lou Reed

Tapestries might appear a curious medium for a contemporary artist to work in, considering that the format derives from its usefulness in keeping drafts from passing through porous castle walls, and the ease with which you can roll it up and transport it on horseback. (Painters, like Peter Paul Rubens, have historically found a practical appeal in them too, since they could adapt popular compositions into tapestries that would fetch multiple times the price of the original canvas.)

Visitors admiring Self-Portrait (Yellow Raincoat)at the opening

Visitors admiring Self-Portrait (Yellow Raincoat)at the opening

But Close is not drawn to working with the loom for its throwback novelty—rather, he says, he says he like tapestries because he feels the medium "hasn't been used up yet." Looking at the works in this exhibition, it's easy to believe he has a point.

Click the slide show above for a tour of the show.