The artist Ajay Kurian has a way of making sculptures, inflected by sci-fi themes and leavened with wit, that seem at once light-hearted and startlingly urgent. A curator on the side who has produced excellent shows under the rubric of Gresham’s Ghost—including at least one in the rising art scene of his native Baltimore—Kurian has been receiving growing acclaim for his work, which he shows through his gallery, 47 Canal, and which was recently included in the show “Open Source: Art at the Eclipse of Capitalism” at Galerie Max Hetzler. Here, Kurian shares his favorite works from the NADA New York art fair.

Art fairs are difficult. They’ve become the bread and butter of most galleries; they’re destinations, tourist attractions, and just incredible money-making vehicles. So it’s no surprise that fairs laced their way into the contemporary art world rather easily. For many artists, solo booth presentations are now as important as solo exhibitions in a gallery and just as valid a part of your CV.

This doesn’t mean that it’s not a symptom of larger consumption problems in the art world, but suffice to say that the art fair is something that has nevertheless produced a new culture. It has produced a new kind of gallery, a new kind of artist, and a new kind of journalism. The increasing proliferation of “best of” lists, “must see” lineups, and top tens have taken up a good chunk of our current cultural bandwidth, making it increasingly difficult to feel as though participating in another is of any importance or relevant in creating a further discussion on why certain things are important to us. So I’m not going to do that here.

When I was in school, when anyone invoked intuition as their guiding principle, I assumed it was a kind of romantic camouflage meant to hide a lack of ideas. It was the language of a past era, of Abstract Expressionism, even Expressionism, making the word feel vestigial, or like leftovers to a long abandoned meal. Ten years later, I realize how miserly that youthful assertion was. Intuition isn’t some empty, romantic concept. Intuition is the living sense that derives from all of your experiences, intelligence, attitude, knowhow, and discernment. It is the complicated DNA of your past, your recollections, your immediate loves, your quiet hates, and your ugly truths. It moves with you and, oftentimes, without you, but it is precisely you who gives it the life and the clarity it has.

Intuition girded by rigor can sometimes produce something wonderfully and unforeseeably new. It can produce a voice you’ve never heard, a style you’ve never seen, a thing so beguilingly out of joint with the world-as-is. When you hone your own sense of intuition, I think it’s easier to see it happening in others. I see the beginnings of this in the work of Lukas Geronimas, whose graphite covered bathtubs are somewhere between magic school bus and prison cell.

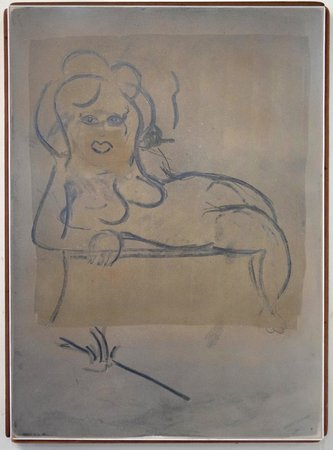

Lukas Geronima's Custom Framed Dust Drawing (2), 2015, at David Petersen Gallery

Lukas Geronima's Custom Framed Dust Drawing (2), 2015, at David Petersen Gallery

The scrawlings and surface treatment feel so powerfully evocative of so many ways of being with oneself that I feel a little bad that I didn’t think of the treatment myself.

I see it in the work of Puppies Puppies.

Puppies Puppies's Coronas on Swiffer (Green), 2015, at What Pipeline

Puppies Puppies's Coronas on Swiffer (Green), 2015, at What Pipeline

There’s a vernacular forming that doesn’t seem too jaded, or ironic, or one-dimensional. It’s just enough out of reach of a quotable Post-Internet art interface to be something more subtle, something a little more searching—where its acerbic edge seems to be tempered with a more critical element. It’s a voice still in development, but it feels like it’s coming from a genuine place.

Atmosphere and intuition are linked for me. To be able to build an atmosphere means that one has an intuitive sense of history, culture, image, text, touch, and taste, all held together by a kind of subjective gossamer. I admire Hayley Silverman’s recent work for that reason.

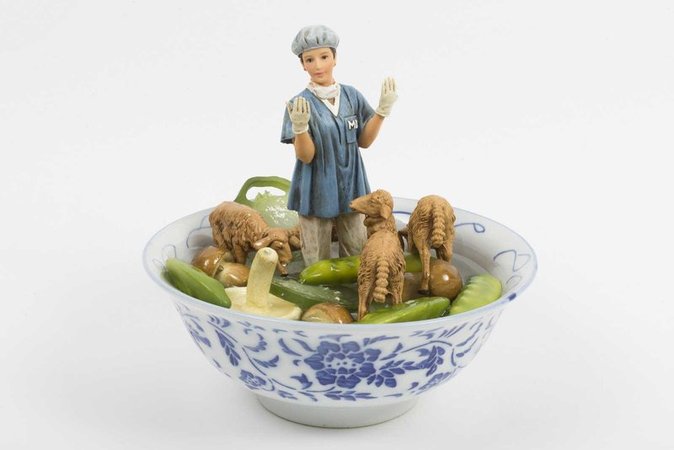

Hayley Silverman's Fairness, 2015, at Bodega

Hayley Silverman's Fairness, 2015, at Bodega

Her sculptural noodle bowls are like tea leaves, legible because of a possible syntax, but not the way we might read history from the page. What we see inside each bowl is more akin to plucking a few visceral notes and creating a strangely charged atmosphere.

Sara Ludy, too, has a way with creating a highly distilled atmosphere with images of spaces that slip memory and the virtual into the form of a hendiadys, each reforming the other endlessly.

Sara Ludy's Window #2, 2010-2015, at bitforms

Sara Ludy's Window #2, 2010-2015, at bitforms

There are also artists that are dedicated in their inquiry into a series of ideas and things and processes, like Wyatt Niehaus.

Wyatt Niehaus's Lights Out, 2013, at Gallerie Hussenot

Wyatt Niehaus's Lights Out, 2013, at Gallerie Hussenot

Exploring automation and what this means for the factory, for the individual, and for our economies has resulted in a variety of videos and images that has an powerful foreboding visual rhetoric. The methodical doesn’t banish intuition—it just doesn’t surrender to it.

Lastly, an artist I don’t yet know what I think about is Mindy Rose Schwartz.

Mindy Rose Schwartz's Self-Portrait as an Aromatherapy Candle, 1999, at Queer Thoughts

Mindy Rose Schwartz's Self-Portrait as an Aromatherapy Candle, 1999, at Queer Thoughts

I don’t have much to say about her work since I just found out it exists, but my gut tells me there’s something there.