Science tells us that the human body emits a chemical substance known as pheromones that can have an aphrodisiac effect on those around them, stirring passions and inciting our animal instincts. So, can artworks give off pheromones too? Let’s just say our lab results are inconclusive at this junction, but from an a priori analysis of anecdotal evidence it’s clear that certain pieces can exert an powerfully seductive allure on collectors. These works below have alarmingly high levels of irresistibility, so be forewarned.

STEAL

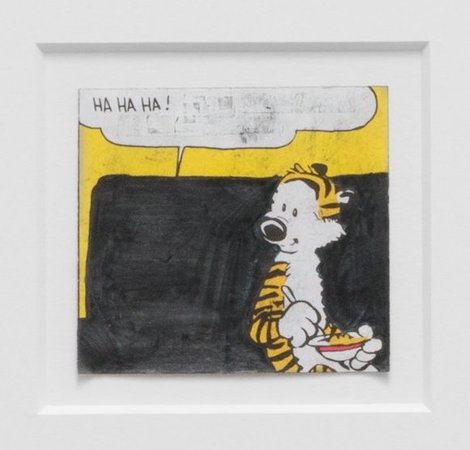

TONY LEWIS

Untitled (HA HA HA!), 2016

Pencil, graphite powder, and correction fluid on paper

$2,500

The young Chicago artist Tony Lewis has entranced curators and collectors alike with his pared-down paintings that play ghostly tricks on text, winning him a place in the last Whitney Biennial and prominent showcases like Art Basel Unlimited. He’s also a Calvin & Hobbes superfan. (He has called Bill Watterson’s comic strip “my childhood’s literary and artistic savior.”) Now, Lewis has combined these two tracks of his creative life into a deeply personal series of works—like this one—that blow up redacted scenes from Calvin’s adventures with his imaginary tiger, eliding Calvin as if he were a god whose depiction was forbidden. For certain fans of Garfield Minus Garfield, this is about as good as it gets.

SPLURGE

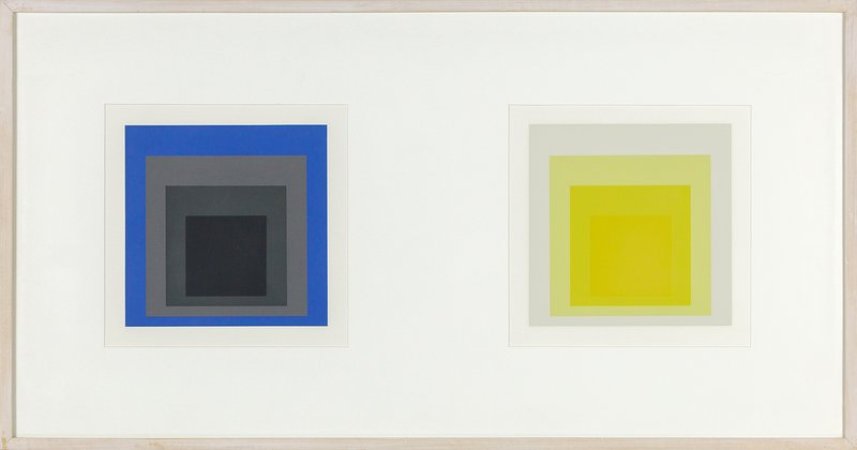

JOSEF ALBERS

Formulation: Articulation, 1972

Screenprint

$6,500

The most iconic motif of famed Bauhaus paragon Josef Albers, the “Homage to the Square” series was the staging ground for the artist’s theoretical investigation of the interplay of colors, harmonizing them into Modernist symphonies for the eye. Begun in 1950—the year Albers, who had fled the Nazis, became chairman of the design department at Yale’s art school—and continued to his death, the series is remarkable for its extraordinary spectrum of visual effects within a rigid geometric framework, for which there were only four variations. This pairing, finely executed on Mohawk paper, is testament to Albers’s penetrating genius as a theorist, and the ageless appeal of his minimalistic art.

STEAL

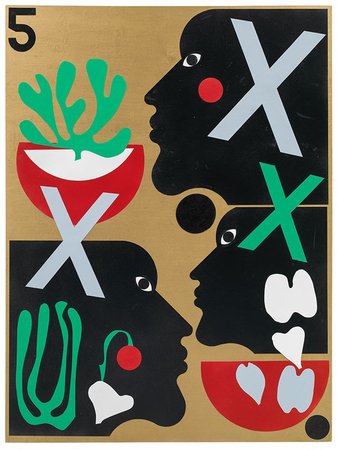

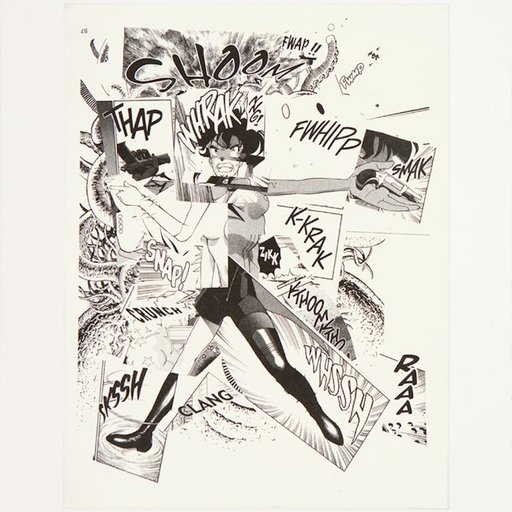

NINA CHANEL ABNEY

Untitled, 2016

Archival pigment print on Hahnemuhle German Etching paper

$1,500

Nina Chanel Abney uses an bold, vibrantly colorful idiom (reminiscent of collage and animation) to address the deeply painful crises that arise from America’s insane plague of racism, sexism, and gun-addicted authoritarianism. Her art has clearly hit the current moment perfectly, and Abney is one of the greatest political artists to emerge from the Black Lives Matter era. But to only see her work through the lens of politics would be a mistake—her versatility as a painter and wonderfully evocative, flexible style suggest that she’s the real deal, an artist to pay close attention to. This piece, with its cutout aesthetic borrowing from both typesetting (those “x”s are chilling) and Matisse’s late decoupage works (those plants are clearly his signature Monstera deliciosa), is a potent distillation of this rising star’s themes, and benefits Harlem’s nonprofit Laundromat Project to boot.

SPLURGE

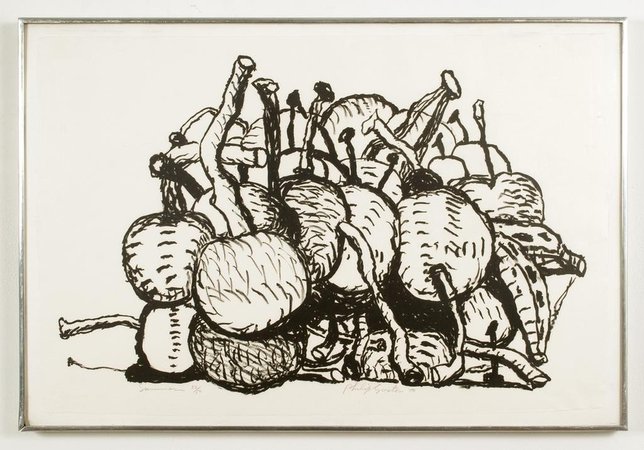

PHILIP GUSTON

Summer, 1980

Lithograph on paper

$8,000

One of the most fascinating and yet still under-appreciated artists of the 20th century, Philip Guston (born Goldstein) did it all: he got kicked out of high school alongside his lifelong friend Jackson Pollock, went to Mexico and became a hero of the Muralismo movement (earning accolades from Siqueiros), returned to New York as a hard-living Cedar Bar fixture of the Abstract Expressionist era, then abjured abstraction in his later decades to create the dark, brooding golems of his soul that he so excelled at. This print, made in the last year of Guston’s life, is an absolute masterstroke. A pile of balls with nail-like protrusions, they echo the hairy eyeballs his tormented figures but actually depict a happier subject, as can be seen from a vivid painting he made of the same imagery, only in bright red. They’re cherries. How good is this lithograph? It’s in the permanent collections of both MoMA and the Tate.

STEAL

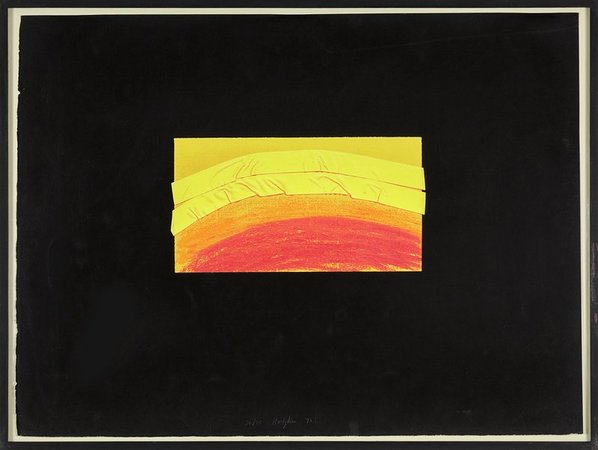

HOWARD HODGKIN

Indian Views, 1971

Lithograph

$3,500

Howard Hodgkin has been a towering figure of British contemporary art for so long now—he won the second-ever Turner Prize, for instance, in 1985—that there’s a risk of taking him for granted. Don’t do it. Still painting at age 84, though now from a wheelchair, Hodgkin is a master of color and composition, often dealing with colors within a rectilinear frame, like Albers, but wresting far more operatic emotions from his palette, and making the frame itself a dynamic participant in the painting. (He often creates faux “frames” within his canvases, or lets his paint wander onto the frame itself.)

This piece was made in 1971, when many of Hodgkin’s peers were jumping into the cool, surface-privileging remove of Pop, but when he decided to instead delve further into his own experience, taking a train through India and making thees prints from the landscapes he glimpsed out the window. With yellow bands that resemble strips of fabric joining its warm, sunset colors, this lithograph is a delightful pop of beauty and pictorial wit.

SPLURGE

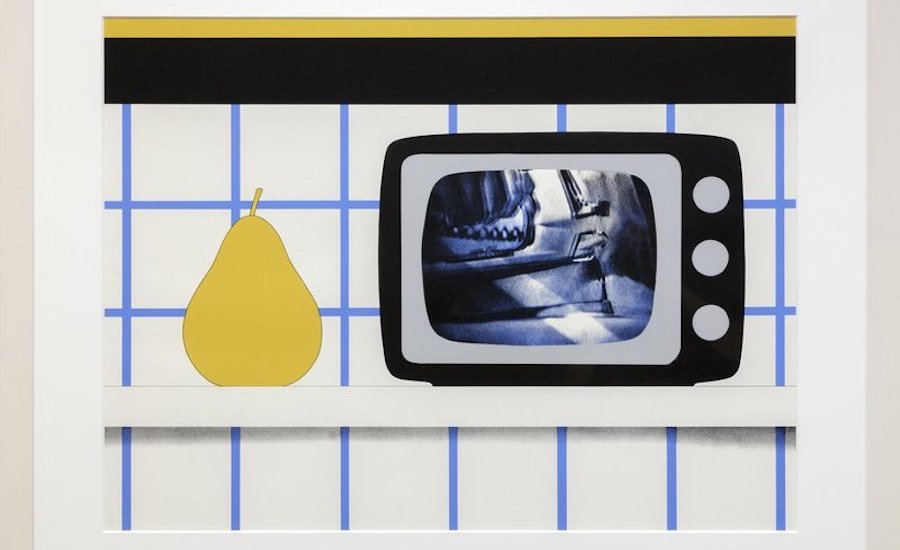

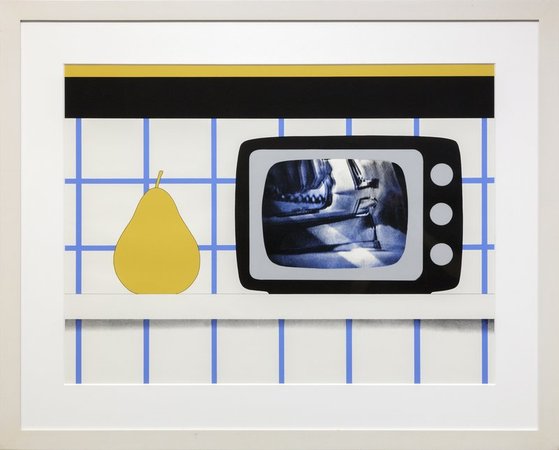

TOM WESSELMANN

TV Still Life, From 11 Pop Artist III, 1965

Screenprint

$9,500

Can you be overexposed but still under-sung? Yes indeed, as you can see with the case of Tom Wesselmann. A fixture of art fairs for years due to his frankly sexy bikini-line nudes, rendered as flattened cartoonish figures that draw the eye, he still never had a career retrospective in America during his lifetime (he died in 2004) partly due to the breast-centricity of so much of his art—a situation that recently led the New York Times to label him “the most famous Pop artist you don’t know.”

That now is changing, fast. In 2014 a full-scale retrospective of his work toured from Montreal to the U.S., and when Almine Rech opened their first New York space last month, they chose to debut with a splashy Wesselmann show (including an installation piece whose components include a “live tit”). European curators, meanwhile, go gaga over his Pop still lifes (like this one), some of which the artist blew up to room-sized proportions.

At a time when Alex Katz—a clear stylistic fellow traveler who helped Wesselmann get his first solo show—is having a major late-career moment thanks to the ministrations of Gavin Brown, it’s very easy to imagine this overlooked artist as next in line.