The artist Yinka Shonibare MBE is renowned for sculptures of headless figures in vibrantly colored, richly textured costumes that recall Britain’s imperial era—though their visual splendor slowly gives way to themes of colonialism, globalism, and identity that he approaches in exceptionally nuanced ways. Much of the ambiguity in his work—which is simultaneously celebratory and critical, or satirical—is traceable to the fact that he spent his formative years between London and Lagos, Nigeria. The art that results is a biting expression of what it means to live in an emphatically global era.

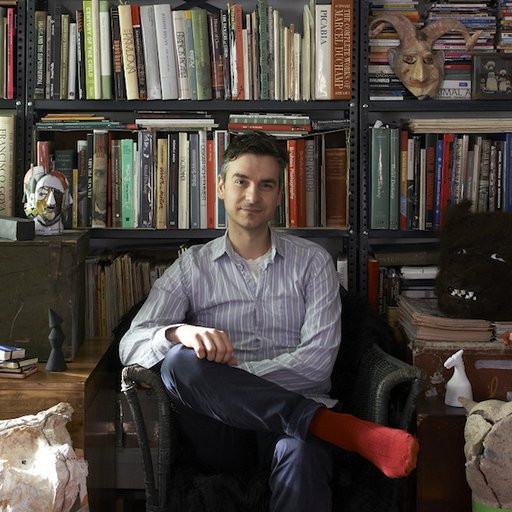

Shonibare wears his Britishness as a badge of honor, literally: after being awarded an MBE by the queen in 2002 he has appended it to his name on all occasions. Artspace editor-in-chief Andrew M. Goldstein spoke to the artist—who recently debuted a new sculptural edition, Kaleidescope, with the Multiple Store—about the themes suffusing his work, his experience coming up in the YBA moment, and the complex trajectory of African art.

Can you talk a bit about your upbringing, and how it informed your view of the relationship between Britain and Africa?

I was born in London and I only lived there for three years before my parents moved back to Nigeria, then I lived in Nigeria until I was 17 years old. In Nigeria I experienced a lot of colonial influence—things like going to Catholic school and being taught by Irish nuns, learning British nursery rhymes, and so on. And we all had to speak English at school—if you spoke a different language you’d get in trouble—so you learned to operate between the two cultures, really. Then, of course, there was the issue of the power relations between the quote-unquote third world and the first world. There were a lot of aspirations to go abroad and basically to see what the mother country looks like. Many Nigerians live in between—you have to be well-versed in the Western world, because that’s where the economy is. So a Western education was a valuable thing to have.

It was when I came to the U.K. for university that I discovered racism, which I hadn’t realized actually existed. I also discovered Britain’s relationship to the ex-colonies, and the way people of African origin living in the West were having to find their own identities within these power relations and the inequalities of class that I discovered here as well. So I had to deal with all of this.

How did your art develop during this time?

When I was at art school I was doing work about the Soviet Union and the political movement it was going through at the time, which was Perestroika, and one of my tutors at Goldsmiths said to me, “You’re African. Why aren’t you producing authentic African art?” And I thought, well, what does that actually mean? What’s authentic? So, really, my work evolved out of asking those questions, and the issue of how people perceive you through various stereotypes.

Then I discovered the batik fabrics in Brixton Market, and I learned that they had this very interesting origin: even through they’re seen as African fabrics in Africa, they’re actually Indonesian fabrics that were originally produced by the Dutch for the Indonesian market, but because industrially produced fabrics weren’t popular in Indonesia they were introduced to West African market. I like the global trajectory of the fabric, and the way that we perceive it as being essentially African but it’s not.

The period you were at Goldsmiths is now forever associated with the birth of the YBAs, and you’ve been identified with them ever since, even though the style and themes of your work differed vastly from theirs. What was your experience of the YBA moment like?

Well, the funny thing is that these things are usually linked together after the fact. Sure we went to the same private views and openings and we knew each other, but we never actually worked as a unit. It was the time of Margaret Thatcher when I came out of college, though, and there was no way any of us would have been picked up by a commercial gallery, so the fact was that we had no choice but to make things happen for ourselves. Only certain very senior artists had the opportunity to do anything with the galleries then, really. So quite a number of us just took over buildings and did exhibitions, like Damien Hirst did with “Freeze”—it was before the property boom in London, so you could find lots of empty properties.

Some artists showed together, but that was just out of necessity—it was never a planned group. The only thing that linked us together was shared desperation, basically, because there was the recession and public funding for everything was being cut. So Margaret Thatcher almost pushed us to get on with it, in a way, and try to make things happen for ourselves. None of us had any money, and we didn’t have studios, so we worked out of squats.

I don’t quite understand the YBA thing, because some people were left out of it who were there at the time. I guess what ties me closely to the group is that fact that I was in “Sensation” when it came to the Royal Academy in 1997 from the Saatchi Collection, even though I wasn’t Charles Saatchi’s favorite—he only bought two pieces of mine. [Laughs] But I never felt part of any group, really—I just wanted to do my own thing.

Before the YBA era, the most prominent black artists in London were people like Eddie Chambers and Donald Rodney of the BLK Art Group, who were making racially charged work influenced by Amiri Baraka’s Black Arts Movement in the United States. Your interests diverged from theirs. What did you make of their work at the time?

Funny enough, I knew all of them—I knew Rodney, I knew Eddie Chambers, I knew Keith Piper. But I saw their work as being closer linked to the Harlem Renaissance and the African American experience, and, as somebody coming from Africa, I wasn’t angry enough because I didn’t have that experience. I was relatively new to the race issue because of my background and upbringing, so it wasn’t really my concern. I had to go in a different direction, and I was also very interested in what was happening with continental theory, deconstruction, postmodernism, semiotics, and the cultural discourse generally. I did not feel that I wanted to be quote-unquote parochial about my practice, and I was deeply influenced by philosophy and Derrida and Baudrillard, which I was reading at the time. So I wasn’t looking at my art in terms of race issues but in terms of aesthetic concerns and design concerns and semiotics, and that’s where we separated really.

You’ve mentioned semiotics, which brings to mind the famous passage in Roland Barthes’s Mythologies about Paris Match cover of a black Algerian soldier saluting the French flag. Your work seems to be about the politics of representation.

Yes, it’s definitely about the politics of representation. You know, I was reading Edward Said’s Orientalism and Frantz Fanon’s Black Skin, White Masks, and Goldsmith’s was very theory-based, too. So that was my main interest.

One of the continually interesting elements of your work is that themes of colonialism are often intertwined with motifs like the study, or globes, or telescopes, and other elements related to the Enlightenment and exploration. And the mannequins in your sculptures, it must be mentioned, are neither white nor black, but have an intermediate tan skin tone. How do you treat the notion of progress in your work?

I guess that on the one hand there’s the promise, or the fallacy, that the enlightenment will liberate you, and that if you can forget your superstition and your religion and your culture you can be “like us.” And unfortunately that 19th-century Enlightenment view is still informing our foreign policy now, governing the way we deal with Iraq, Afghanistan, and all these other places. I think if we had a simple understanding that these places had their own systems of law and culture before the West arrived on their shores—if we had a mutual respect for everybody’s culture—it would be very nice. But instead we go on wanting to impose a 19th-century Enlightenment view on these people.

So I see my work as exploring the two sides of this issue, because the complexity in my work arises from that fact that while I critique the establishment I also want to become part of it as well. So it’s not as disparaging as people might think—I’m not suggesting that I don’t want the best of the West. I want those things. That’s why I took on the alter ego of the dandy in my work [in the 1998 photographic series Diary of a Victorian Dandy], because he’s a character who is both an outsider who is trying to gain access to the establishment as well as an insider. I think these traits are reflected in my own life within the art world, that I’m the outsider who wants to be on the inside.

In fact, in a recent interview, you said you that love the queen, and “can almost describe [yourself] as a royalist.” What is it about the trappings of monarchy that appeals to you?

I think there’s something kind of lovely in the ritual and all that pomp and ceremony. But, at the same time, it’s more provocative to be on the inside and to be associated with the powers that be—it’s just a much more complex relationship, because if you understand your own subconscious desire for power and come to terms with it, you become a much more difficult character to manage. It’s complicated, too, because I’m not sure about my honesty—I don’t know if in my subconscious I genuinely do want power, to enjoy those trappings. It’s a more honest position to say you do. Because most freedom fighters end up being dictators anyway. If you look at all of the struggles around the world that tends to be the trajectory—people start out as revolutionaries and they end up being tyrants.

You’ve mentioned a little how race operates differently in Britain than in America. What do you make of the outrage over institutional racism that is sweeping through the United States right now in the protests across the country?

Well, the beatings and the killings of young unarmed black men in the United States have been very sad, and they have to be understood in relation to Jim Crow and the American history of lynching. It’s quite a different history from ours, and I think the racial divide in the United States cuts deep as a historical issue—you had a civil war in the United States, and those wounds don’t heal easily. It’s something that only Americans can resolve among themselves, and it will take possibly a thousand years.

In the U.K., most black people came as voluntary immigrants, which is a very different thing from being taken on a boat against your own will. The issue in the U.K. is more about class than race, because if you’re black and have a fairly good education—if you went to one of the best schools here—and you’re mostly middle class, you’ll be fine.

It’s fascinating to think that, just as we say we’re two countries divided by a shared language, art can have such vastly different registers depending on where it’s shown.

Yes, it’s very different. For example, even though it may superficially look like my work, Kara Walker’s work is so different from mine in the sense of its relation to American black history. What’s going on in the United States is very sad, especially with an African American president in power. And I don’t know what Obama could possibly do about it.

You have spoken about how your experience as an African in Britain has clearly done much to shape your work. Another aspect of your identity is the fact that since your youth you have been paralyzed by transverse myelitis, an inflammation of the spinal cord. Over the years, you’ve assembled a formidable bottega of assistants who help you to execute your complicated, often large-scale installations and films. How has your disability informed what you do?

Actually, although people do talk about my disability, the way that I work is in fact not very different from how most artists work now, like Jeff Koons or Damien Hirst. If you do 10 exhibitions a year, you can’t possibly be making everything yourself, able-bodied or not. So I don’t actually feel that I’m very unusual at all—I probably would have ended up working this way even if I was able-bodied since I get so many projects. I have a studio with a production manager and then I work with a lot of different costumers, sculptors, filmmakers, and so on. The way I work is like the way most busy international contemporary artists work now, actually.

What are you working on now?

We’ve got a show coming up at James Cohen Gallery in New York and we’re working toward a show at the William Morris Gallery in London and also a major show in South Korea next year, as well as a number of art fairs around the world.

It seems as if the art establishment is paying an increasing amount of attention to art that is coming out of or otherwise relating to Africa. There’s a new fair of African art that takes place in London during the week of the Frieze Art Fair, Angola won the Golden Lion for best pavilion at the last Venice Biennale, and now the next Venice Biennale is being organized by Okwui Enwezor, a Nigerian-born curator renowned for his expertise in African art. What do you make of this development?

I mean, I think it’s a good thing. But I’m also always baffled by the fact that Western artists can exist easily within the global diaspora and be located anywhere and travel anywhere, while for some reason African artists have to be located purely within that continent. I think that should change. People should see that African artists can move around like everybody else and they don’t necessarily have to pinned to the continent. if they choose to be there that’s fine, but they should be able to simply exist in the global diaspora in the same way Western artists are able to be free.

Also, although people are always trying to market things nicely, but you run the risk of seeing artists of African origin as fashion items, and then the danger with that that sort of classification is that you could say, “Well, we’ve done China—next year let’s do Africa.” And then it’s, “Well, we’ve done Africa—now let’s do the Middle East.” But artists in Africa are working all the time. They’re not just fashion items.