“America Is Hard to See,” the title of the new downtown Whitney Museum ’s inaugural exhibition, refers to a poem by Robert Frost and, in a looser sense, to the melting-pot concept of American identity. But it just as easily describes the former state of the museum’s permanent collection, very little of which was visible at any one time in the space-starved Marcel Breuer building on the Upper East Side.

That will change when the new Whitney opens on May 1 with a triumphant 600-piece collection showcase that fills every single one of the capacious new galleries. Many objects are coming up for air after decades in storage; quite a few are being exhibited for the first time in the museum’s history. Meanwhile, some new acquisitions—including at least one work so fresh from the studio that you can smell the paint, as well as a lacuna-filling photograph by Asco, a Los Angeles Chicano artist collective from the '70s and '80s (above)—are making their own high-profile debuts. The Whitney’s curators are weaving these hitherto hidden works in alongside old favorites to refresh, expand, and diversify the story of American art. ( Ellsworth Kelly , meet Carmen Herrera; Andy Warhol , may we introduce Malcolm Bailey?)

Below is our guide, informed by conversations with the Whitney’s chief curator Donna De Salvo and assistant curator Jane Panetta , to some of the works that are just now emerging into view.

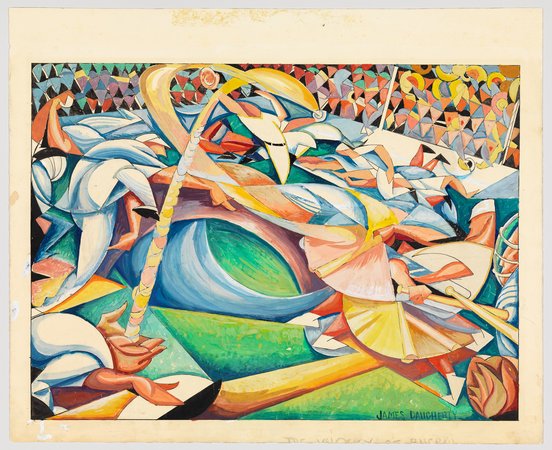

JAMES DAUGHERTY

Three Base Hit

, 1914

Last shown in 1989

James Daugherty's

Three Base Hit

, (1914). Pen and ink and opaque watercolor on paper,

James Daugherty's

Three Base Hit

, (1914). Pen and ink and opaque watercolor on paper,

Installed on the museum’s eighth floor next to Joseph Stella’s Luna Park , James Daugherty’s lively watercolor applies the lessons of Italian Futurism—perhaps gleaned from the Armory Show of 1914 , the year the work was made—to, of all things, the game of baseball (an unusual subject matter for a movement that celebrates speed and dynamism, not to mention one that has Fascist associations.). “These are the kinds of things that we found in the collection that we really started to think about,” says De Salvo. “It speaks to this idea of an American subject, and yet the Futurist influences, Balla and Severini, come through.” Panetta concurs, “Everyone was really excited about that work. It’s meshing Futurism with this ultimate American pastime.”

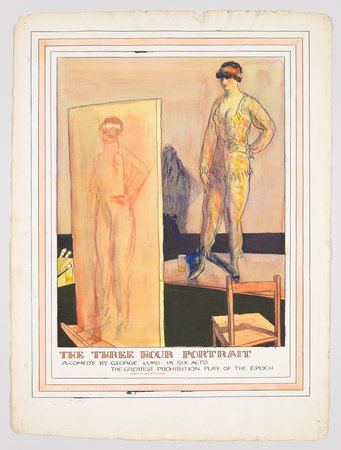

GUY PÈNE DU BOIS

A True History of Eight West Eighth

, 1921

Never previously exhibited

Guy Pène Du Bois's

The Three Hour Portrait

, (1921) from

A True History of Eight West Eighth.

Watercolor, pen and ink, and graphite pencil on paper,

Guy Pène Du Bois's

The Three Hour Portrait

, (1921) from

A True History of Eight West Eighth.

Watercolor, pen and ink, and graphite pencil on paper,

Like the old Whitney, the new museum has a small gallery off the lobby. For the inaugural exhibition, it’s been filled with works that date from the collection's formative years. These witty watercolors by the artist, critic, and social gadfly Guy Pène du Bois depict the goings-on at the first incarnation of the Whitney, the Whitney Studio Club at 8 West 8 th Street, where he had had a solo show a couple of years earlier. It looks to have been quite a party; everyone is dressed to the nines (with the exception of the life-drawing models) and, Prohibition notwithstanding, in their cups.

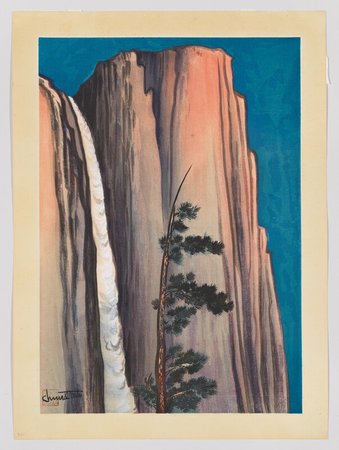

CHIURA OBATA

World Landscape Series “America,”

1928-30

Some new acquisitions; series never previously exhibited

Chiura Obata's

Evening Glow of Yosemite Fall

, 1930, from the series

World Landscape Series "America"

Chiura Obata's

Evening Glow of Yosemite Fall

, 1930, from the series

World Landscape Series "America"

These striking prints by the Japanese-American artist and longtime Berkeley professor Chiura Obata present the classic American landscapes of Yosemite and the High Sierra in the tradition of Hokusai’s 36 Views of Mount Fuji , executed with a traditional Japanese woodblock technique. De Salvo compares them to Ansel Adams’s photographs, on view nearby. “There are a number of works that we have recently acquired to expand the narrative of how we think about American art, which has a lot to do with who counts as an American artist,” she says.

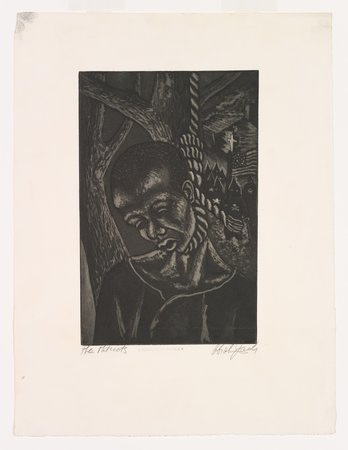

VARIOUS ARTISTS

Lynching drawings and prints

Some new acquisitions; many never previously exhibited

Abraham Jacobs's

The Patriots

(1937). Etching and aquatint

Abraham Jacobs's

The Patriots

(1937). Etching and aquatint

Rounding out the Social Realist offerings in a section of the show called “Fighting With All Our Might,” on the seventh floor, are several drawings of lynchings by artists including Paul Cadmus, Harry Sternberg, and Abraham Jacobs. These wrenching works date from the 1930s, when many artists were involved in efforts to pass legislation banning lynching. “It’s about artists as activists,” De Salvo says. The display includes new acquisitions such as Jacobs’s The Patriots , a close-up of a head in a noose. It also signals a larger effort, in the show, to mix works on paper in with important paintings and sculptures. (Ben Shahn’s big history painting The Passion of Sacco and Vanzetti hangs nearby, as do several panels from Jacob Lawrence’s War Series ).

MARY ELLEN BUTE

Synchromy No. 4: Escape

, 1937-8

New acquisition

“There were some glaring omissions in the collection that we were really trying to rectify, and this is one of them,” Panetta says of this abstract short by the painter-turned-filmmaker Mary Ellen Bute (which will be screened in a black-box gallery on the seventh floor). Set to Bach’s Toccata and Fugue in D Minor , the film stars an orange triangle that is trying to liberate itself from a series of shifting black grids. “To have a woman in the narrative this early on, working in this medium, in this abstract way, was really exciting for us,” Panetta says. “It does a lot of work, as a single work.”

HEDDA STERNE

New York,

New York, 1955

Last shown in 1967

Hedda Sterne's

New York, N.Y.,

1955. Airbrush and enamel on canvas.

Hedda Sterne's

New York, N.Y.,

1955. Airbrush and enamel on canvas.

Sharing a gallery with Abstract Expressionist trophies such as Pollock’s Number 27, 1950 and de Kooning’s Woman and Bicycle (1952) is this arresting red-and-green painting by Hedda Sterne, the only woman to be included in the famous “Irascibles” group portrait in LIFE magazine (in 1951). Like that photograph, New York, New York 1955 seems to capture a particular place and time. But it also, as Panetta says, “looks like something that could have been made in the past 10 years,” thanks in part to Sterne’s fuzzy, airbrushed lines (so different from the thick impastos of her peers). De Salvo agrees, “It really looks very contemporary. We’ve all been looking at the technique, and how fresh it looks.”

CARMEN HERRERA

Blanco y Verde

, 1959

New acquisition

Carmen Herrera's

Blanco y Verde

, 1959. Acrylic on canvas

Carmen Herrera's

Blanco y Verde

, 1959. Acrylic on canvas

Panetta singles out this spare diptych by the 99-year-old Cuban-born painter Carmen Herrera as “the most important new acquisition we’re including in this show.” This striking work from her “Blanco y Verde” series of white-and-green paintings has pride of place in a section of the exhibition called “White Target,” which explores postwar abstraction by the likes of Frank Stella, Brice Marden, and Ellsworth Kelly. “Herrera is someone we had identified a long time ago as a key player in this hard-edged abstraction conversation, one that we didn’t have properly represented,” Panetta says. The Whitney will also be giving Herrera a solo exhibition, slated for fall 2016.

MALCOLM BAILEY

Untitled

, 1969

Last shown in 1980

Malcolm Bailey's

Untitled

, 1969. Acrylic on composition board

Malcolm Bailey's

Untitled

, 1969. Acrylic on composition board

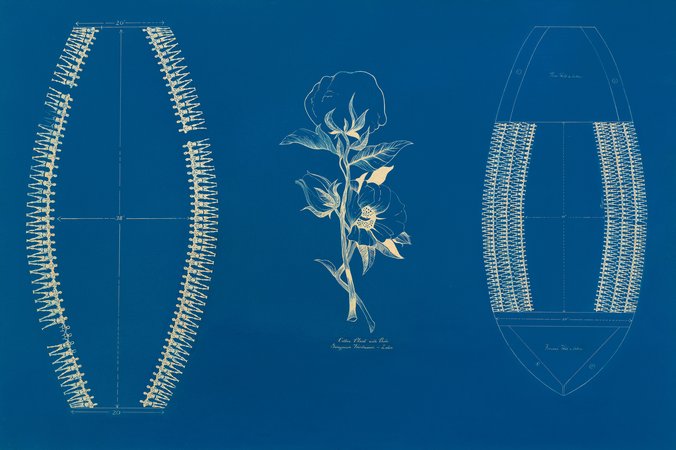

The Whitney’s postwar holdings are especially rich in Pop art , thanks in part to a large 2002 gift spearheaded by then-chairman Leonard Lauder, and the curators are certainly pulling out the Warhol s, Lichtensteins, and Oldenburg s for the inaugural exhibition. They’ve also unearthed this contemporaneous canvas by Malcolm Bailey, which offers up delicate outlines of slave ships and a cotton plant in lieu of more typically Pop consumer goods. As Panetta observes, “It dovetails with some of the things Warhol was doing—the diagrammatic things, the before and after, even the seriality of the Coke bottle.” She also notes that the Whitney gave Bailey a solo early in his career, in 1971, as part of a series of shows dedicated to African-American artists: “One thing that was exciting to us is to make some reference to this institutional history, to an artist we championed early on in an important way.”

KAREN KILIMNIK

The Hellfire Club Episode of the Avengers

, 1989

New acquisition

Karen Kilimnik's

The Hellfire Club episode of the Avengers

(1989). Fabric, photocopies, candelabra, toy swords, mirror, gilded frames, costume jewelry, boot, fake cobwebs, silver tankard, audio media player, and dried pea.

Karen Kilimnik's

The Hellfire Club episode of the Avengers

(1989). Fabric, photocopies, candelabra, toy swords, mirror, gilded frames, costume jewelry, boot, fake cobwebs, silver tankard, audio media player, and dried pea.

One of the few big installations in “America Is Hard to See,” this signature work by the “scatter artist” Karen Kilimnik was acquired just last year from the collector Peter Brant at the urging of curator Scott Rothkopf . Inspired by the 1960s British television show The Avengers , it combines apparently slapdash, let-the-pieces-fall-where-they-may construction with fangirl obsession. “That gallery has two ideas playing out,” says Panetta. “One is connected to identity politics and the body as the site for image-making and commentary. The other side is a place for work that’s less explicitly political. The Kilimnik, as much as it’s of that moment, feels very personal.”

NICOLE EISENMAN

Achilles Heel

, 2014

New acquisition

Nicole Eisenman's

Achilles Heel

, 2014. Oil on canvas

Nicole Eisenman's

Achilles Heel

, 2014. Oil on canvas

The Whitney owns a lot of work by Nicole Eisenman, who has been in two of the museum’s Biennials, but the curators wanted something brand-new for this special occasion. “We got it right out of her studio,” Panetta says of this recent painting, a moodily surreal view of one of the artist’s favorite neighborhood haunts (the Achilles Heel bar, in Greenpoint). “She has really begun to get more involved in issues related to the recession and the plight of America,” Panetta says. “I think it works really nicely in that last gallery where artists are struggling with those questions in a more oblique way, or even struggling with the question of what to paint. Eisenman talks about people coping and drinking.”