With his strong self-imposed limitations, the veteran abstract painter Thomas Nozkowski is a model for younger artists daunted by the infinite possibilities in contemporary painting. His drawings and paintings, scaled to fit in cramped apartments and the back seats of sedans and made according to a rigorous routine at his Hudson Valley studio, convey a remarkable sense of freedom within constraint. Ranging from free-flowing forms to rough grids to branching, map-like compositions, his works on canvas and paper are all connected by his subtle color shifts and responsive hand.

The artist Thomas Nozkowski

The artist Thomas Nozkowski

Artspace caught up with Nozkowski during the installation of his latest show at Pace Gallery’s 510 West 25th Street location (through April 25) to discuss his love for the Shawangunk mountains, his fears of carpal tunnel syndrome, and what a 15th century painting by Pisanello has to say to contemporary painters.

I thought we might start with your introduction to the New York art world. You come from a suburban, working-class background. What was your earliest exposure to art?

I was raised in a couple of households that, for whatever reasons, had lots of art materials lying around. I had an aunt who was a schoolteacher, so for as long back as I can remember on Saturdays and Sundays I would have piles of paper and crayons and poster paint and was just left to work. I always enjoyed it. On the other hand, I never imagined for one second that I would be an artist until I got to high school. I had a great teacher, an Abstract Expressionist of no real art-historical import who had been to NYU after World War II and knew about the New York scene. This guy knew this hip world that I really aspired to—I didn’t care so much about being an artist, I just wanted to be in New York City and be a beatnik. I grew up in northern New Jersey, not too far from the City, but culturally about as far away as you could imagine. The City was always there as this thing that I wanted to have.

What were some other early influences?

I came to New York in 1961 to go to Cooper Union. I wouldn’t have been able to go to college except that Cooper was free and open to everyone who could get in. My time there was wonderful. The faculty for the most part was Abstract Expressionists, with a few older Bauhaus types mixed in. At the time at Cooper you went five days a week for eight hours a day—it was like having a job—and it was very much oriented toward the craft, toward the materials. It was a good school.

You made a decision soon after you graduated to shift your focus from sculpture to painting. How did this come about?

I’d always wanted to be a painter. I loved painting and was probably considered a pretty good painter in school, but by the time I graduated from Cooper in ’67 I was really at a dead end. I knew I wanted to paint, but I couldn’t figure out how to paint. This was the ‘60s—a lot of political forces were in play, Conceptualism was getting its start. It was very, very hard for me to get my head around how to work, so I took a few years off and made sculpture. In fact, the first artworks I showed in New York were sculptures at Betty Parsons Gallery. It took me a while to find my way back into painting.

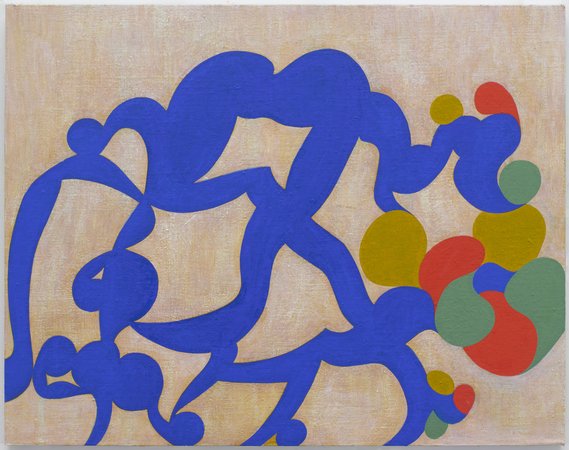

Untitled (MH-5), 2014. Courtesy of the artist and Pace Gallery.

Untitled (MH-5), 2014. Courtesy of the artist and Pace Gallery.

How did you find your way back, in the end?

A couple of things happened. For political reasons, I found the kind of large scale, macho-man abstractions of early SoHo beneath contempt. These were painters that I liked and admired, and I remember going to shows and seeing a painting that was 20 feet long—it’s like the 800-pound gorilla that sits wherever it wants to sit. I didn’t want to paint that way, and I decided I would paint at a size that was scaled to my friends’ apartments, that could hang in a three-room walkup tenement on 7th Street. That was the first big decision. I don’t think I would have kept to that for long, except that once I made that decision I discovered how easy it was to put an idea in the world, look at it, and then wipe it off and do something else if it’s no good. Suddenly, I could go through hundreds of ideas in the life of a painting. When I did large paintings like I did in art school, it could take days to change a color.

The liberation of choosing a small scale was one thing that allowed me to get back into painting, and the other was the decision that everything I did would be based on something in the world. Initially, some of those ideas were really stupid, really corny, but slowly, in part due to working on this scale and feeling able to try anything and everything, it really got me someplace. It made me happy, anyway.

These two decisions have characterized your work since the ‘70s. What are the other advantages or drawbacks you’ve found in consistently working in this way?

Again, the idea that you can work very quickly is crucial. Another component is the idea that you can have these things in your home, that it’s not a special project to have an art collection. You can have 10 paintings hanging on a wall—what a feast! On a practical level, you can carry them around with you. I have a house in the country and a house in the city, and they fit in the backseat of the car. The issue is to be able to keep working, to be able to pursue your dreams for lack of a better term. This allowed me to do that.

Do you have a certain method to approaching a painting, or is it more of an improvisation every time you sit down?

You have to remember that my teachers were Abstract Expressionists, so the idea of knowing what a painting is going to end up being just drives me crazy. That’s absolutely against the rules. I want to be happy in my studio. I want it to be exciting, and I don’t want it to be a job. Coming from the working class, I know what work is—if I wanted a job, I’d get a job. I want to be an artist.

Given that formative experience with Abstract Expressionism, your commitment to painting from life—basing your paintings on "something in the world"—is striking. Why did you choose to work this way?

The nice thing about the world is that everything stretches out to touch everything else, creating these references and connections beyond the visual scene at hand. There’s a painting in this show with some Matissean curvy shapes painted in a Matisse blue—that’s not an accident, it was a decision to draw upon that blue for that particular move.

As soon as you tell people there’s some source in the world they want to know what it is, but when you tell them they say, “oh, well that’s really boring.” Well, sure it is! What’s interesting is how far you can go with that, what you can find in it or make out of it. That’s the reason I don’t title my pieces, because in fact people would be so disappointed if they knew what commonplace things these are. They’re things that I care about, things that I love, things that I thought would be worth spending a couple of months trying to pursue.

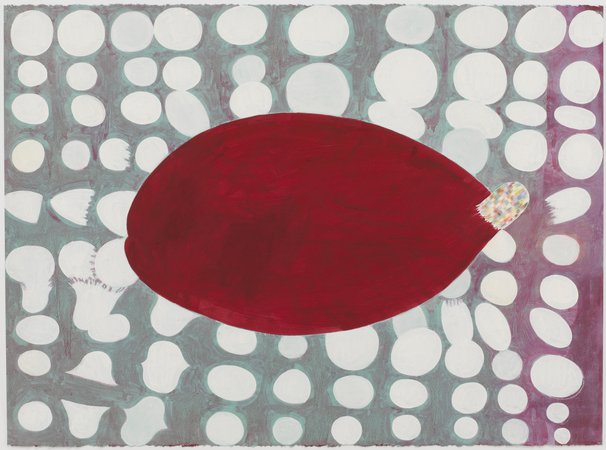

Untitled (09-32), 2014. Courtesy of the artist and Pace Gallery.

Untitled (09-32), 2014. Courtesy of the artist and Pace Gallery.

Your drawings and works on canvas are notable in part because of their variety—they’re recognizable as your work, but there’s no overarching style and certainly no serialized production of variations on a single theme. How do you keep things fresh and unpredictable?

Part of it is willful—I just don’t want to do the same thing over and over again. When I first started working this way, I thought that if I was as absolutely, painfully sincere as possible about what I was doing I would within some short period of time develop a signature style. I thought that somewhere deep inside was this signature style that would come out if I just let it. To my amazement, no such signature style came to be! I’ve come to understand the signature style as a weakness—that’s as far as you can go. It’s not where you want to go, it’s where your system takes you and stops. It’s like the Peter Principle, “failing upwards.” How far can you fail?

As I get older, having had a lot of shows and having made a lot of paintings, I do see some commonalties between the works—certain moves that I often fall back on. I’m not spooked or scared by these kind of commonalties—in fact they interest me, and I can play with them a little bit—but I do like the idea of saying “look, every question is different, every problem is different, why shouldn’t every painting be different?” You don’t want to get carpal tunnel, always doing the same damn painting!

You caused a bit of a stir with your 2010 show here at Pace Gallery, where you showed drawings done after your paintings were completed rather than the expected preparatory works. What’s the relationship between your drawings and your paintings?

Basically, I do two kinds of drawings. The first are standalone drawings that are multimedia—crayon, graphite, colored pencil, ink, anything—that tend to be fairly small in size, under 11 by 14 inches. I love doing those more than just about anything in the whole world. I have to stop myself from spending my whole life sitting there drawing.

The other kind of drawings are large, 22 by 30 inch oils on paper, and these happen on my second easel, a sort of drawing board turned sideways. I'll be working on a painting for many months, and something interesting happens in the painting that I know I’m going to get rid of, that’s not going to stay. It’s just a moment in the life of the painting. I’ll take the paint that’s on my palettes, and I’ll go over and work on an oil on paper. These are almost like snapshots in the evolution of a painting.

Since I love drawing so much, after I did the paintings for that last show I decided to do a set of drawings that actually come from these paintings. It was a lot of fun, but boy, it confused the hell out of a lot of people.

Untitled (09-47), 2014. Courtesy of the artist and Pace Gallery.

Untitled (09-47), 2014. Courtesy of the artist and Pace Gallery.

What about the works in this new show at Pace, paintings that are based on a group of drawings?

In 74-odd shows, this is the first time I’ve done a show where many of the paintings came from drawings. Last November, the editor/publisher of Esopus magazine, a small publication of literature and visual art projects, asked me to do 16 pages for the new issue. It was the most horrible assignment—it was due whenever I wanted, so I was in big trouble from the get-go.

I do a lot of walking in the area of the Hudson Valley where I live, on the Shawangunk Ridge, and I’ve worked with a lot of organizations preserving land on the Shawangunks. There’s an area near Kerhonkson where several hundred acres of land have recently been acquired by non-profits, and I’ve spent the last two years hiking around this area, mapping it and so forth. I decided to do drawings from this area for Esopus, and in fact I even drew a map of where the trails were for the magazine, so in theory someone could follow the map and find the locations. Not a chance that anyone will, of course, but that was the idea.

I liked the drawings very much—I did about 45, and 15 were printed in the magazine. I liked them so much that I started doing a lot of paintings related to not only the drawings, but to that area in general. More than most of my shows, this is very much about place—a place where I’ve lived for the last 10,000 years, at least in my mind.

What about the place where you work? What's your studio space like, and how does it affect your process?

My studio is a nice, large room in the country with north-facing windows—a simple, clean space. I have two easels, one of which takes paintings—oils on linen on panels. The other is that drawing board turned vertical that I can pin sheets of paper to and draw or paint on as well. Right now, in my studio, there are probably eight or so paintings on the wall that are in varying degrees of completion.

I like to work on a few things at once—if they get very dry, I’ll generally scrape them down and open them up again physically. I work seven days a week unless I’m in the city installing a show or being interviewed, and I usually work at least four hours a day, usually in the morning. I spend the afternoon doing drawings and busy work. I have one assistant whose job it is to do anything that I would have to do instead of painting.

Untitled (L-22), 2014. Courtesy of the artist and Pace Gallery.

Untitled (L-22), 2014. Courtesy of the artist and Pace Gallery.

Is that craft-oriented mentality gleaned from Cooper Union still present in your process?

You learn to respect your materials, and not so much in a crafty way, but in the sense that you want your materials to speak back to you. In my head, everything is perfect. It’s when I manifest that in the world that suddenly things collapse or change or mutate. How do you make yourself receptive or sympathetic to those things that materials are pushing back at you? “Hey, you had a perfect blue in your head? Well, what do you think of cobalt medium dark?”

How do you deal with these unforeseen emergent properties of the medium?

You work with them. It’s like writing a song—you have to find that rhyme at the end of the line. Having to go for that, needing that to work, will sometimes put you in a place that you never imagined.

For the last 30 years, all of my paintings have come from something in the real world, some place, idea, person, something. At its best, that focus will put me in a zone where I’m not comfortable, where I don’t have an answer. I have to find that answer in the act of making a painting. For me, that’s totally liberating.

So do you see your paintings as a kind of solution to a problem?

What do we mean by a solution? What is a resolved painting? Where is a painting supposed to take you? For me, it’s something of a circular route. The world is full of things you can make paintings of: abstract things, real things, ideas, bowls of fruit, you and I sitting in this room. If you look around and see a hundred things you can make a painting of, I’ll see a different hundred. Why do I choose to do one thing and not something else? To me that’s the mystery of art, of all art in all cultures in all times. Why did somebody want to do this? Why were they attracted to that? Why did their eye go there, and why did they need to make something? That’s a great mystery, and it’s not an arbitrary question—it’s the basic question of art. It speaks to our personalities, to who we are.

When I look at landscape painting from 11th century China I think it’s the most beautiful stuff I’ve ever seen. I don’t have a clue as to why you’d make something like that or how you’d do it, but it’s incredibly beautiful nonetheless. The Benin Bronzes, cave paintings, you name it—in all these forms of art, I think what we see is the sense that another human being did this, that they saw something, wanted something, desired something so intensely that they would take this journey and develop this thing in a rich and complex way. Cardinal Newman’s motto was “Heart speaks unto Heart,” and I think that’s really what it is.

Pisanello's The Vision of Saint Eustace, c. 1438-1442

Pisanello's The Vision of Saint Eustace, c. 1438-1442

Speaking of works that speak to you: you’ve referenced Pisanello’s The Vision of Saint Eustace several times in other interviews. What’s so special about this painting?

The Vision of Saint Eustace is quite remarkable in that it has this sense of being the first time. It’s like the last Gothic painting and the first Renissance painting in northern Italy. You have animals in tapestry-like, almost Egyptian profiles, and then the horse turns completely volumetric. That idea of the firstness of things, of wanting to do something that may even be beyond your abilities—I think there’s a lot to be said for doing something as well as you can. When I was teaching, I always had undergraduates who said things like “How do you draw a perfect circle?” I think a perfect circle isn’t half as interesting as the best circle you can draw. That’s your circle.

As a painter, you have a project: there’s a thing in the world you want to make a picture of. How do you make a picture of a feeling, of a mood, of a quality of life, even of something like a sunset? The answer is that you just start, and you do it as well as you can. At a minimum, you will succeed in having a picture of how well you could do something. You’re reaching for that sunset.