There used to be a bar in Antwerp called Les Cinq Anneaux, or The Five Rings. The Belgian painter Luc Tuymans once went in there to ask the bartender whether the five, vertically arranged rings in its sign held any meaning. “He told me it didn’t,” the artist recalls in the Phaidon book Luc Tuymans: Is it Safe?

This was the exact answer Tuymans had hoped to receive. “At the time, I was looking for some kind of symbol, like the painted star, the cross or the Olympic Games logo,” he explains. “But I didn’t want to use any of those specifically. The rings were the perfect solution to my problem and gave the series an eerily symbolic and ritualistic feel.”

Over the past five decades this masterful painter, whose works form part of the permanent collections at MoMA, the Tate, and the Met among other world-class institutions, has been creating images that leverage this eerie sense of unease from a wide variety of both sinister and innocuous sources. A Japanese serial killer, an assassinated African leader, a wide array of politicians, and officials within the Third Reich, have featured in his paintings, alongside images from reality TV, recreations of photos of friends, and even the lampshade that hangs in the artist’s bedroom.

Admirers of his paintings are often gripped by a sense of unease – not because the painting is clearly sinister, but because they open up a whole world of apprehension that seems to lie in otherwise uncategorised imagery.

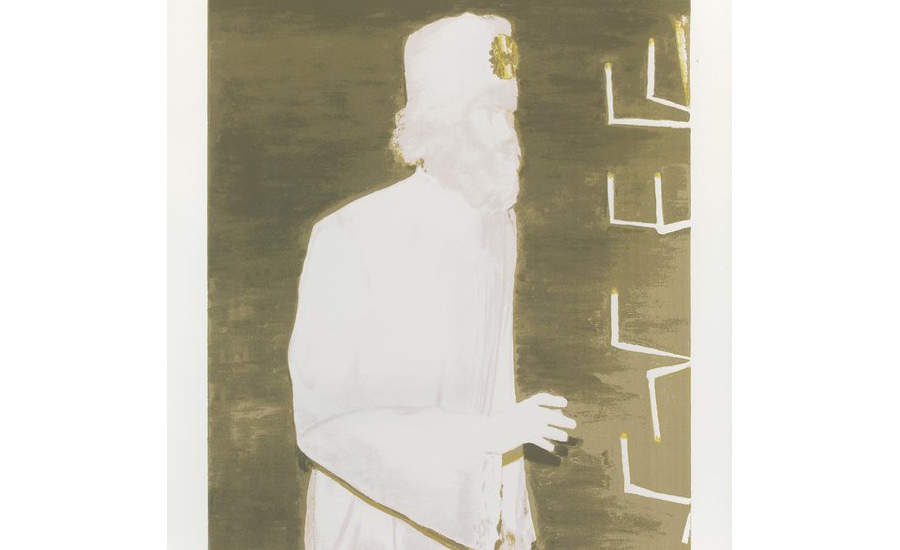

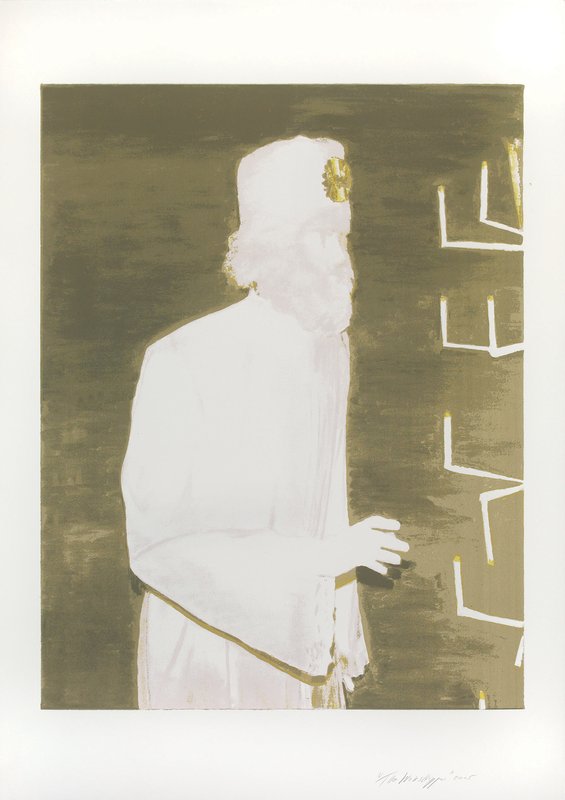

LUC TUYMANS - The Worshipper, 2004

Silkscreen print with special edition hardback book in slipcase

The Worshipper, Tuymans’ 2004 painting and print (the latter of which forms part of Phaidon’s collectors’ edition monograph on the artist ) is a perfect example of this process. The picture was based on a Polaroid photograph Tuymans took of a costumed mannequin at the Musée International du Carnaval et du Masque in Binche, Belgium. This Belgian city is known for its annual Easter carnival, which dates back to the 14th century, and remains a prized, though peculiar part of European pageantry and heritage. Its museum celebrates this heritage, though not every visitor will look at its costumed displays and think of the joy of Mardi Gras.

For his 2005 exhibition, also called Les Cinq Anneaux, Tuymans combined the five rings canvas with The Worshipper and a painting of Belgium’s own World Trade Center. “Together these images combine notions of religion, folklore and fundamentalism,” he reasons.

Luc Tuymans - Marcwathieu, CC BY-SA 3.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

Luc Tuymans - Marcwathieu, CC BY-SA 3.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

Today those sinister, imprecise qualities picked out in this silkscreen remain undiminished. In a slightly different light, The Worshipper could be the source material for some confected, ‘fake news’ online paranoia story, or an all-too-real cult, finally exposed to the light of day.

Yet for all of The Worshipper ’s latter-day digital fungibility, Tuymans’ print also makes the most of its source material. “I was mostly using Polaroids, which attenuate the colours, making things unclear and imprecise,” he writes. “I like to work with materials that are inconsistent because they leave more room for interpretation.”

Collectors can also enjoy the capacious, interpretive aspect of The Worshipper The silkscreen forms part of Phaidon’s collectors’ edition of Tuymans’ Contemporary Artists series monograph; find out how you can order the print alongside a special edition of Tuymans’ s book here . And see more of the artist's work for sale on Artspace here.