“How inappropriate to call this planet Earth”, wrote Arthur C. Clarke, “when it is clearly Ocean”. The science fiction legend had a point. Seas cover some 70% of the globe’s surface, and were where terrestrial life first began some four billion years ago. And yet for modern humans this is a hostile environment, a place that – for all we exploit and despoil it for both commerce and leisure – remains the closest thing we know to an alien world.

It’s no surprise that artists have long been fascinated by the sea, and the attraction and terror it elicits in frail humanity. We might think of Jan Bruegel the Elder’s painting Christ in the Storm on the Sea of Galilee (1596), which depicts the apostles quaking at the awesome power of a maritime tempest while Jesus slumbers undisturbed, or Pierre-August Renoir’s Sunset at Sea (1879), where sky and water dissolve into an otherworldly, near-abstract play of red, purple and orange light.

Today, the sea still exerts a strong hold on contemporary artists’ imaginations. The six works gathered here - all available to buy now - approach the sea as an index of the ineluctable passage of time and a place of fathomless mystery, a mirror of human feeling and a place where we might escape ourselves, somewhere that is both mundane and also strangely magical. As the oceanographer Jacques Cousteau put it: “The sea, once it casts its spell, holds one in its net of wonder forever”.

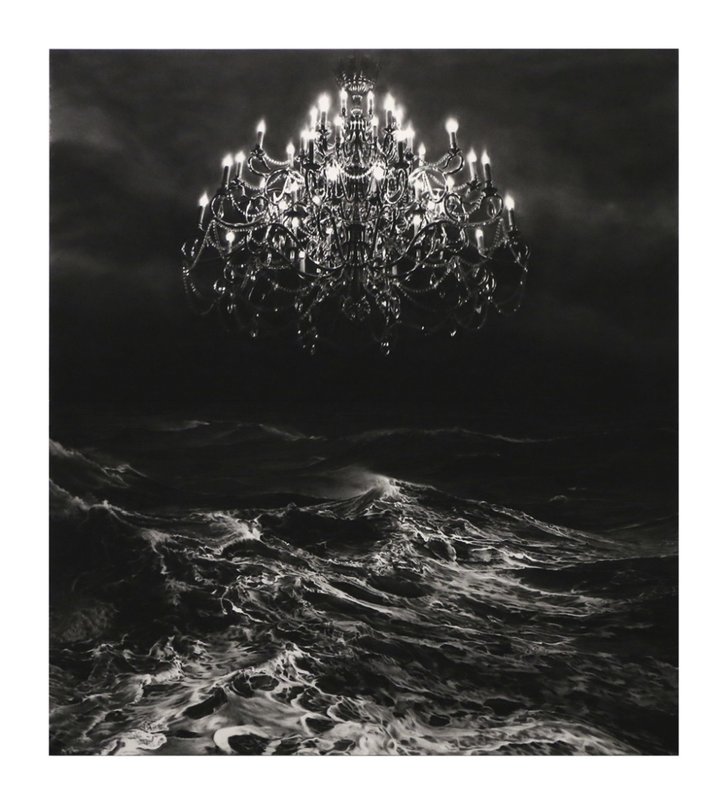

Robert Longo, - Untitled (Throne Room) (2017)

Above a roiling, primordial sea, whose mountainous waves are capped with snowy spume, there hangs an unaccountable object: a vast chandelier, its lights blazing against the black night sky. Robert Longo’s print Untitled (Throne Room) is a work that juxtaposes the terrible beauty of the ocean with a glittering symbol of aristocratic grandeur, elemental power with the human ability to bring forth electric light. Is this a vision glimpsed by some dehydrated, half-mad sailor, a close cousin of Herman Melville’s Captain Ahab, or Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s Ancient Mariner? Or might it be a literal transcription of a literary simile, comparing the heavens to a chandelier? The Biblical book of Job recounts how ‘God hung the stars in the sky’. Who, we might wonder, installed these lamps, and from what are they suspended? What unknown force prevents them from crashing down into the inky waters, and blinking out for good?

As essay in postmodern baroque, Untitled (Throne Room) takes cues from both the ceiling frescoes of 17th Century Italian painters such as Pietro da Cortona and Andrea Pozzo, and also from Hollywood sci-fi blockbusters. We might easily mistake the chandelier for an alien mothership, hovering against the canopy of night. In this work Longo – a key American artist who has been the subject of retrospectives at both the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and the Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago – does not seek to resolve the contradictory references and insoluble questions he puts into play. Rather, he lets them churn, like his dark and dreadful sea.

In this forbidding image, the noted Brooklyn-based photographer Rachel Sussman positions the viewer as though they were on the prow of a ship, approaching an icy landmass across a bleak, crystalline sea. Compositionally, it owes something to the Swiss Symbolist painter Arnold Böcklin’s celebrated canvas Isle of the Dead (1880), but while Böcklin depicts a ferry crossing the river Styx to the classical Greek underworld, Sussman takes us towards Elephant Island near the South Pole, a place not of death, but (perhaps surprisingly) of life. The cliffs that rise up into the steely skies are covered in clumps of Antarctic moss, which have clung tenaciously to the same craggy, windblown spot for some 5,500 years. To contextualise: this flora is 500 years older than Stonehenge, and around 1000 years older than the Great Pyramid of Giza.

Sussman’s photograph forms part of a decade-long project titled The Oldest Living Things in the World, in which the photographer travelled the globe, capturing images of its longest living organisms, from a 9,500-year-old spruce tree in Sweden, to a 3,000-year-old Yareta plant in Chile. The photographer, who worked in close collaboration with botanists and biologists to create this pictorial archive of ancient lifeforms, has said that “I approach my subjects as individuals of whom I’m making portraits, in order to facilitate an anthropomorphic connection to a deep timescale, otherwise too physiologically challenging for our brain to internalize.” Looking at the way the glassy waters meets those fecund cliffs in Antarctic Moss #0212-7B33, we’re reminded of the writer H.P. Lovecraft’s observation that the sea is even “more ancient than the mountains, and freighted with the memories and the dreams of Time.”

Nan Goldin - Valerie Floating (2001)

The ground breaking – and hugely influential – American photographer Nan Goldin is perhaps best known for her series The Ballad of Sexual Dependency (1979-1986), which documented her circle of hard-living bohemiam friends in Manhattan’s then-depressed Bowery district. At once unflinchingly honest and profoundly compassionate, it captured a group of overlooked individuals for whom self-expression and self-destruction were intimately entwined, and for whom craving – for drugs, for sex, for love, for a voice – was a daily companion. As she has said: “My desire is to preserve the sense of people’s lives, to endow them with the strength and beauty I see in them. I want the people in my pictures to stare back”.

In this later work, Valerie Floating, we find Goldin very far from the streets of downtown New York. The artist’s friend (and regular portrait subject) Valerie floats on her back in the tropical waters lapping on Antilles island, her eyes closed, her sense of the boundary between her body and the surrounding sea dissolving. Light sparkles on the gentle waves, and nearly every element in the composition – from the distant hills to the bank of puffy clouds to Valerie’s own prone form – is a long, languorous horizontal. This is an image of (perhaps hard-won) relaxation that teeters towards self-oblivion, a portrait of a modern human regressing to its evolutionary beginnings in the sea – a return to the source.

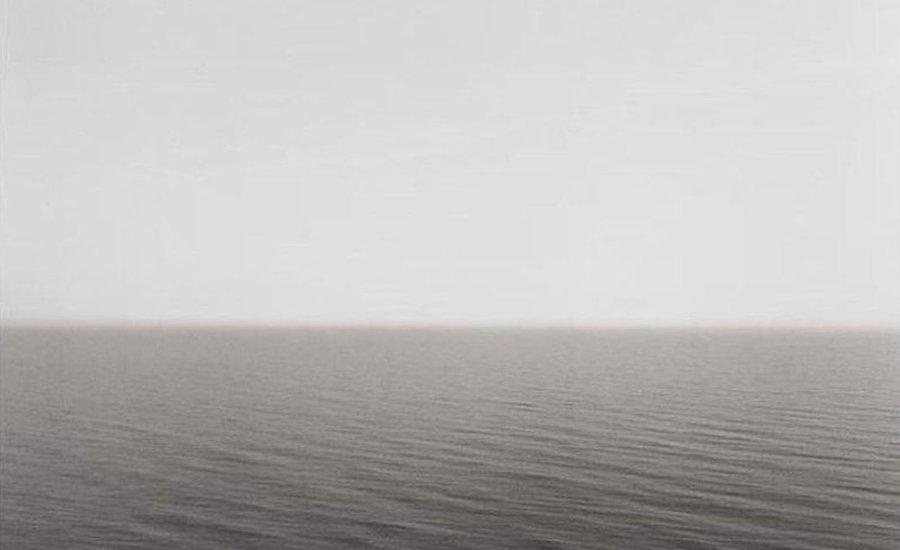

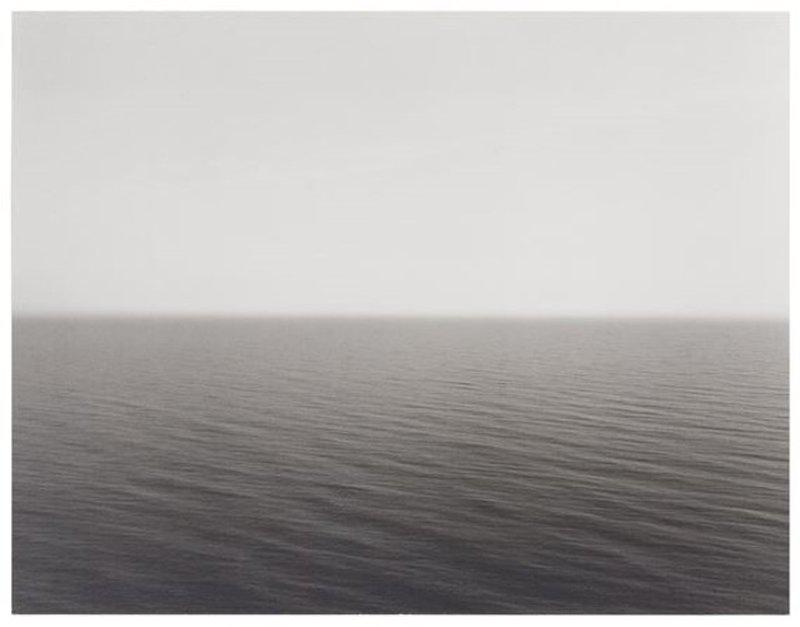

Hiroshi Sugimoto - Time Exposed #367 Black Sea Inebolu 1991 (1991)

“Photography”, claims the seminal Japanese photographer and architect Hiroshi Sugimoto, “functions as a fossilization of time”. By this he means that it not only transforms the temporal into the material, a fleeting vision framed by his viewfinder into a physical print, but also that the result is a record of something that has disappeared, never to return. And yet, if Sugimoto captures frozen moments, then his moments are lengthier than most. Begun in 1980, his Seascapes series – to which Time Exposed #367 Black Sea Inebolu 1991 belongs – employ a large-format camera to photograph various bodies of salt water across the world, from the English Channel to the Arctic Ocean. Significantly, his exposure times run up to three hours. This process is closer to a sculptor making a cast than to the point and shoot brevity of the average snap.

The way the titles of Sugimoto’s Seascapes note locations and dates appears diligent, but is surely laced with irony. Absent colour, or any orienting visual information (a coastline, a ship, signs of local sea life) these stretches of water could be almost anywhere on the planet. Likewise, available technology permitting, they might have been photographed at almost any point in our species’ history – this particular stretch of the Black Sea must have looked much the same in 1991 BC as it did in 1991 AD. In the face of such a realization, Sugimoto’s exposure times, and indeed the lifespan of whole civilizations, begin to feel very brief indeed. If this makes the work feel like an exercise in the sublime, or even perhaps in nihilism, then so too does the photographer’s simultaneous foregrounding and diffusion of what’s commonly called the ‘line’ of the horizon. This ‘line’, of course, is a human concept rather than a tangible phenomenon. What Sugimoto is showing us is simply the endless sky, meeting and merging with the (near) endless sea.

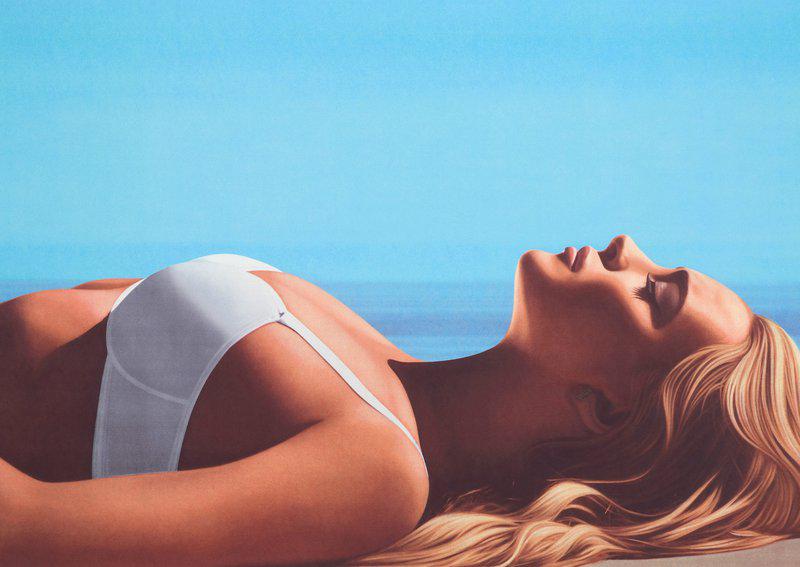

Richard Phillips - Lindsay II (2013)

Like Sugimoto’s Seascapes, the leading American painter and filmmaker Richard Phillips’ screen print Lindsay II is bifurcated by a horizon, but here it is overlaid by the reclining figure of the actress (and noughties tabloid mainstay) Lindsay Lohan. To some degree, we may interpret this image as a meditation on the evanescence, or endurance, of fame. Future art historians, of course, will be familiar with the changeless sea, but will they recognize the star of the 2004 teen movie smash, Mean Girls? As Phillips has commented ‘You have images of important figures that have been painted throughout history. Some [still] have prominence and others faded from prominence. [Portraiture] is subject to harsh speculations on the fortunes of those portrayed”.

While Phillips’ image of Lohan might be placed in the tradition of postwar American photorealist painters such as Richard Estes and Robert Bechtle, it also owes much to the Photoshopped hyperrealism of contemporary celebrity imagery. At least part of the actress’s fame rests on her often-chaotic personal life (which has included stints in rehab), but here Phillips presents her as both physically flawless and utterly serene – cloudless as the blue sky above her, still as the blue sea beyond. Lindsay II, however, is more than simply an iteration of an anyway long-punctured Hollywood fantasy. Time and tide wait for nobody, and somewhere over that horizon a storm is surely blowing in.

Jeremy Deller - The Problem with Humans (2017)

The octopus is a smart cookie. Possessed of some half a billion neurons (roughly comparable to a small monkey), and a notably large brain relative to its size, these eight-legged cephalopods exhibit behaviour that borders on the higher mammalian: they use tools, learn through trial and error, and even appear to do a double-take on catching sight of their own reflections in a mirror. At the same time, octopi remain cognitively very different from other animals that biologists suspect might be sentient, such as dogs and dolphins. As the philosopher Peter Godfrey-Smith, author of Other Minds: The Octopus, the Sea, and the Deep Origins of Consciousness has remarked “If we can make contact with cephalopods as sentient beings, it is not because of a shared history, not because of kinship, but because evolution built minds twice over. This is probably the closest we will come to meeting an intelligent alien”.

The octopus is a smart cookie. Possessed of some half a billion neurons (roughly comparable to a small monkey), and a notably large brain relative to its size, these eight-legged cephalopods exhibit behaviour that borders on the higher mammalian: they use tools, learn through trial and error, and even appear to do a double-take on catching sight of their own reflections in a mirror. At the same time, octopi remain cognitively very different from other animals that biologists suspect might be sentient, such as dogs and dolphins. As the philosopher Peter Godfrey-Smith, author of Other Minds: The Octopus, the Sea, and the Deep Origins of Consciousness has remarked “If we can make contact with cephalopods as sentient beings, it is not because of a shared history, not because of kinship, but because evolution built minds twice over. This is probably the closest we will come to meeting an intelligent alien”.

Looking at his lithograph The Problem with Humans, the Turner Prize-winning British artist Jeremy Deller clearly does not hold out much hope for a fruitful close encounter of the third kind between homo sapiens and cephalopods. Here, an octopus settles on the ocean floor, perusing a volume detailing our species’ shortcomings, one huge orange eye gazing out contemptuously at the viewer. What, then, is ‘The Problem with Humans’? Perhaps our appetite for grilled squid, or for polluting the Earth’s seas. Or maybe this cephalopod feels (to quote Douglas Adams’ novel The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy) that our ancestors made “a big mistake in coming down from the trees in the first place,” or that “even the trees had been a bad move, and nobody should have ever left the oceans”.