For William Shakespeare, the “moon / That monthly changes in her circular orb” was a symbol of inconstancy, while for William Blake it was connected with humanity’s insatiable ambition and greed. In the 18th century poet and artist’s famous engraving I want! I want! (1793), we see a brave, covetous soul mount a ladder from the Earth to the lunar surface, a fantasy that would become reality less than two centuries later, in 1969, when Neil Armstrong became the first man to walk on the moon.

Across the centuries, humans have worshipped both moon goddesses (the Greek Selene, the Igbo Ala) and moon gods (the Egyptian Khonsu, the Hindu Chandra), and different societies have claimed, with various degrees of scientific accuracy, that this heavenly body influences the tides, the menstrual cycle, and even mental health – hence the word ‘lunacy’. It has inspired celebrated artworks as diverse as Casper David Friedrich’s meditative painting Two Men Contemplating the Moon (1825-30) and Kenneth Anger’s woozy avant-garde film Rabbit’s Moon (1950). It is the Earth’s nearest neighbour, but for most of us it remains unknown territory.

In this edition of Group Show, we gather together six works by contemporary artists that focus on the moon. They present it variously as an index of the sublime, and an alien world to be conquered, a subject for scientific study, and a magnet for belief (and disbelief). Each of them, however, touches on its beauty, and its strangeness.

As Joseph Conrad wrote: “There is something haunting in the light of the moon; it has all the dispassionateness of a disembodied soul, and something of its inconceivable mystery”.

Spencer Finch - Moonshadow (2008)

This photograph by the acclaimed American artist Spencer Finch shares its title with Cat Stevens’ classic track Moonshadow (1970), which Stevens has said is based on a childhood memory of being on a Spanish beach at night, and noticing for the first time in his life that it was not only the sun that caused his shadow to appear beside him, but also the “faithful light” of the moon. But while Stevens’ song is about how evanescence of experience means we should live for today (“If I ever lose my eyes, oh I won’t have to cry no more”), Finch’s shot is concerned with the chemical fixing of a fleeting moment. To make this work, the artist photographed a shadow cast under the moon’s pale glow, but instead of developing the exposed print, he sealed it in a lightproof archival box. This is an image, then, that is unavailable to our sense-impressions, but exists all the same, much like the memories in our minds.

Finch’s Moonshadow probes the distance between – and the overlapping of – our physiological and psychological perceptions, the way our interior worlds part and meet and part again with exterior reality. What, we might wonder, would we see if we opened the lightproof box? The label that the artist has affixed to its front tells us that the undeveloped image “would be invisible to the naked eye”, although “the photographic paper bears the photochemical signature of printing process”. Exposed to daylight, this “signature” would, of course, begin to degrade. We might think, here, of how our memories of an experience drift a little further from the truth with every recollection, and of how the moon appears to shape-shift with each passing night.

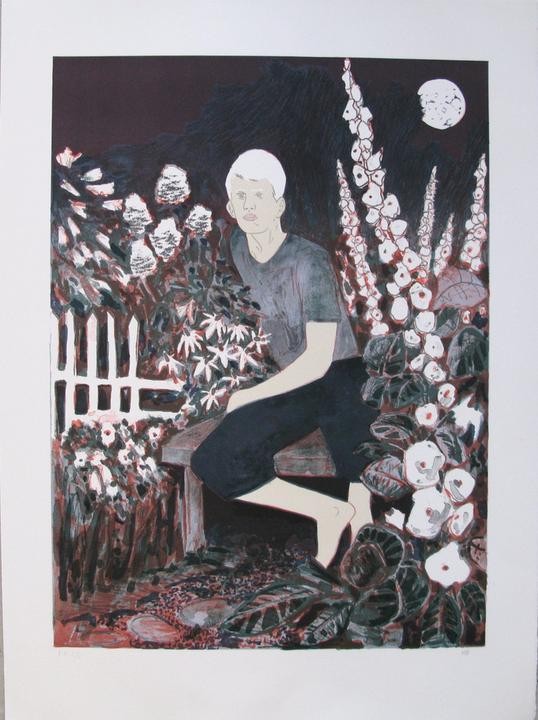

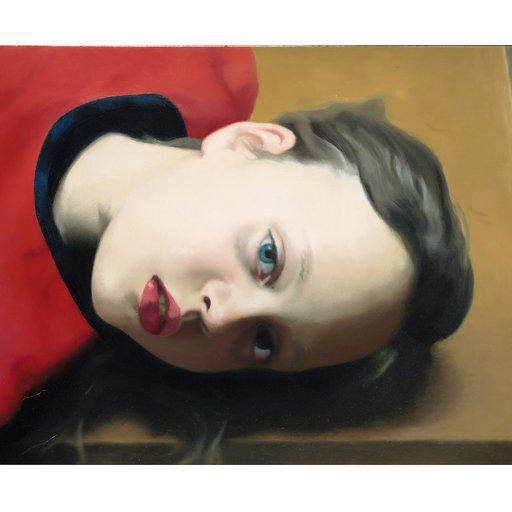

Hernan Bas - The Albino in the moonlit garden (2010)

Albinism is a congenital disorder, which in humans is characterized by a partial or complete absence of pigment in the skin, hair and eyes. More than usually susceptible to sunburn and skin cancers, albino people also often suffer from photophobia, an abnormal intolerance of the sun’s light. Because of their distinct appearance, they face discrimination and even violence in a number of societies across the globe, although in the islands of the Guna Yala archipelago, Panama, albinos are venerated as “children of the moon”, a name that derives from the fact that many of these individuals chose to live a largely nocturnal life, shunning the harsh rays of the sun for gentle lunar light.

In Hernan Bas’s lithograph The Albino in the moonlit garden, the noted Detroit-based artist depicts an albino who also belongs to another minority group that has often faced oppression: gay men. Here, in a verdant glade illuminated by a low, silvery orb, we encounter a beautiful, white-haired youth, who is awaiting a casual sexual encounter, out of sight of the stern, yellow sun. Against the black of night, the garden flowers blaze their pale glory, and we might imagine ourselves in Eden, if only that Biblical Earthly Paradise wasn’t so dully heteronormative. While assignations in moonlit gardens have, over time, become a wilted cliché associated with cheap romance novels, Bas’s print gives this trope new and fecund life.

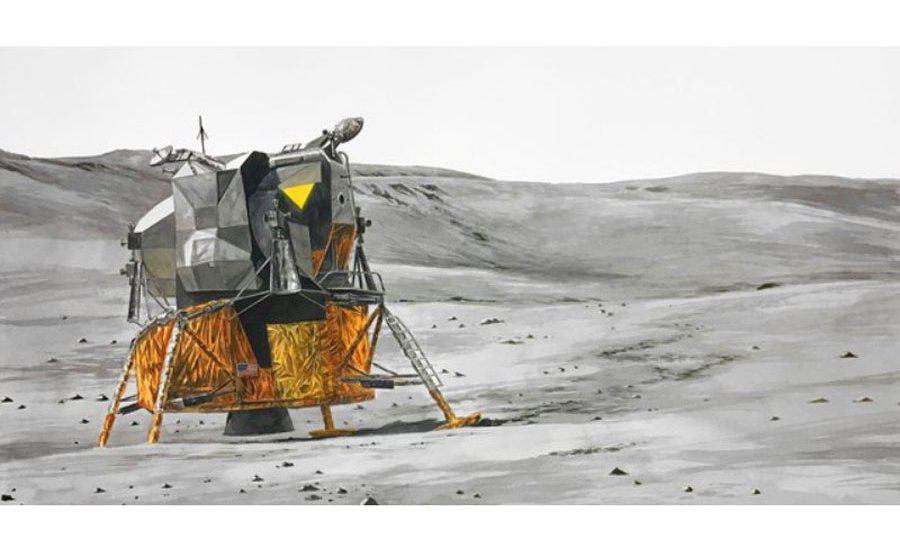

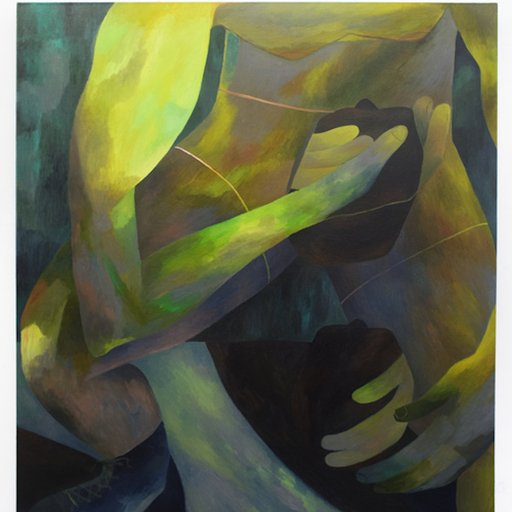

Thomas Broadbent - Lunar Landscape (2019)

In 1962 at the Rice Stadium, Texas, John F. Kennedy gave a speech that has echoed down the ages. “We choose to go to the moon!” exclaimed the US President. “We choose to go to the moon in this decade […] not because [it] is easy but because [it] is hard; because that goal will serve to organize and measure the best of our energies and skills, because that challenge is one that we are willing to accept, one we are unwilling to postpone, and one we intend to win”. Kennedy would be assassinated the next year, but his prophecy held firm. Before the end of the 1960s, Americans had stood upon the lunar surface, and the world would never be the same again.

Painted to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the Apollo 11 landing, Thomas Broadbent’s watercolour Lunar Landscape depicts a bug-like lunar module beached on the grey dust of the moon’s Tranquility Base. Perhaps what’s most intriguing is what’s missing from this image: the astronauts Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin, the first and second human beings to walk on the moon. Are they inside the module? We should take a moment to consider the history of Broadbent’s medium. There’s a comic suggestion, here, that either Neil or Buzz has packed his paint box in his space suit, and has decided to indulge in a spot of en plein air landscape painting. If so, for moon landing conspiracy theorists the resulting image would be no more or less credible than the film footage that captured this momentous event.

Poppy de Villeneuve - Untitled (Something In The Night) (2009/11)

Two years ago, a report in the Chinese newspaper the People’s Daily announced that by 2020 the city of Chengdu would be illuminated at night by a second, artificial moon, in the form of a satellite manufactured by the aerospace contractor Casc that would bath a radius of 80 kilometres in a “dusk-like glow”, obviating the need for street lights and outshining the real moon by a factor of eight. While this sci-fi apparatus is still to launch (perhaps this year’s global pandemic has slowed its progress), it is a telling index of humanity’s desire to control its environment. Once, we believed the heavens dictated our fates. Now, we plot to hang new lights in the sky to blot out the old.

In the rising British film director and photographer Poppy de Villeneuve’s shot Untitled (Something in the Night), we encounter what at first glance appears to be the moon shining above a deserted street, a location pregnant with illicit possibilities. Look closer, however, and we see that this in no unearthly orb, floating in the firmament, but rather a street light (the “tell” is the pool of peachy luminescence a few feet from its pole). Like the Victorian painter John Atkinson Grimshaw, whose nocturnal city scenes often juxtaposed the glow of gas lamps with lunar light, de Villeneuve’s photograph finds romance, even perhaps spirituality, in the prosaic urban environment – somewhere that, under the right conditions, can feel as mysterious as the moon itself.

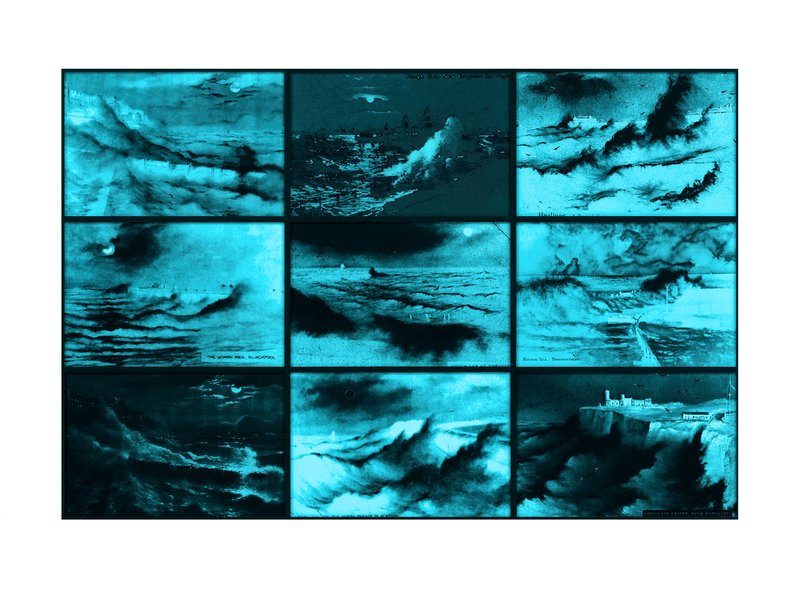

Susan Hiller -Rough Moonlit Nights (Cyan) (2015)

For her influential 1972-6 project Dedicated to Unknown Artists, Susan Hiller gathered together postcards of seaside scenes from numerous British coastal towns, and subjected these ephemeral, popular images to a kind of rogue anthropological methodology. Arranging them by type, and accompanying them with analytical charts and a dossier in which she presented herself as the project’s curator (at that time, an unusual role for an artist to adopt), Hiller drew attention to the unheralded creatives who painted, photographed and tinted these images, and in the process recovered a lost history of labour.

In her photograph Rough Moonlit Nights (Cyan), the artist revisits this earlier work. Here, the grid of postcards is composed entirely of depictions of storm-tossed, nocturnal seas, tinted a deep blue. Prompted by Hiller’s title, we’re reminded of the awesome effect of the moon’s gravitational pull on the Earth’s oceans, which causes their waters to bulge, creating a continuous ebbing and flowing of the tides. In these images, sea walls and even whole coastal settlements are dwarfed by gigantic waves, which threaten to swallow the terrestrial world whole. The moon is 238,855 miles from the Earth, but looking at Hiller’s work, its influence on human life couldn’t feel more proximate.

Betina Samaia - Joshua Tree Noctural II (2010)

“Who am I? What is my place in the universe” These, says the noted Brazilian photographer Betina Samaia, are the “latent questions [that] accompany me”. For her shot Joshua Tree Nocturnal II, she travelled to the titular National Park in southeastern California, a desert wilderness that’s associated with several milestones in art history and popular culture, including the artist Noah Purfoy’s legendary open-air sculptural project 66 Signs of Neon (1965) and U2’s 1987 windswept classic album The Joshua Tree. Samaia, however, was less interested in the Park’s human heritage than in its flora, specifically the hardy, twisting Yucca brevifolia plants native to the region, dubbed “Joshua trees” by early Mormon settlers, because their upturned branches reminded them of the Biblical prophet Joshua raising his hands in prayer.

In this photograph, Samaia shoots a sweeping plain filled with hundreds of Yucca brevifolia, illuminated only by the glinting night sky. Their boughs reaching to the heavens, they resemble a mass gathering of the faithful, hailing the moon as it rises over a distant mountain range (worship of lunar gods and goddesses was, we might note, widespread in pre-Colombian North America). Do these vegetable lifeforms, though, really share our own wonder at that far-off orb? Perhaps the Joshua trees are simply waiting patiently for the break of day, when the nourishing sun will replace the cold and miserly moon?