Right now, when much of the world is stuck indoors self-isolating against COVID-19, the great outdoors can seem like a distant dream. Perhaps it’s time, then, to turn to the landscape, a genre that holds out the promise of (albeit mediated) access to the natural world.

And yet, is this what landscape art really does?

Already long-established in the Chinese tradition, the genre truly emerged in the West during the 17th Century – an age in which, not unrelatedly, what we might recognize as modern capitalism and the scientific method were also gathering shape. The notion of landscape, then, is intimately tied to issues of ownership, knowledge, and (following the flowering of Romanticism in the 19th Century) our interior lives. Moreover, we should always remember that ‘nature’ is a cultural construct, and one that humanity uses to define itself.

Is landscape an exhausted genre? More than most, it is associated with Sunday painters and chocolate box kitsch. Nevertheless, it commands the attention of several of today’s most exciting artists, who have refitted it to focus on everything from environmental degradation to the re-enchantment of the world. In this edition of Group Show, we gather together six outstanding examples of contemporary landscape art from the Artspace store, without a haystack or cornfield in sight.

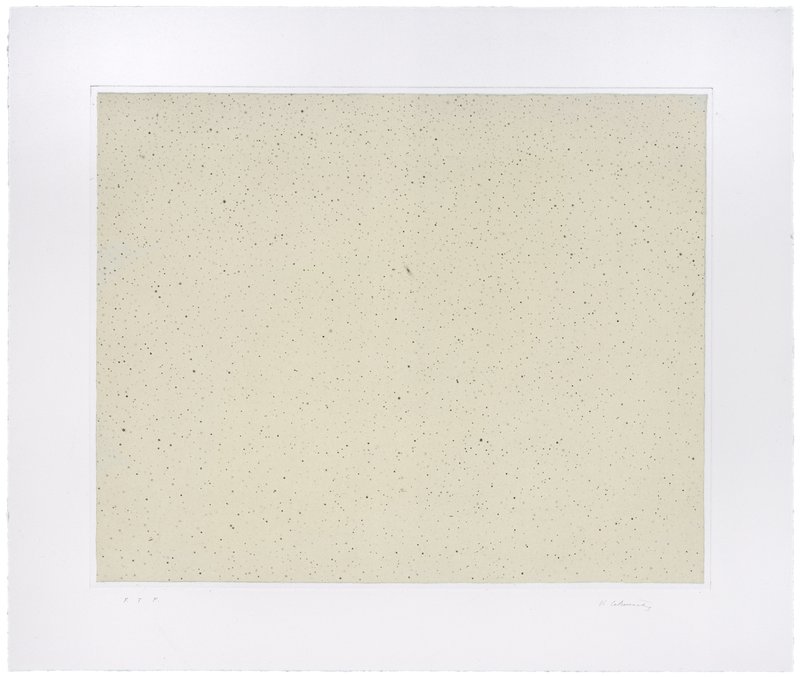

Vija Celmins Night Sky 2 (Reversed) (2002)

The seminal Latvian-born, US-based artist Vija Celmins is best known for her achingly precise, photorealistic drawings of natural phenomena: churning oceans, windblown deserts, and night skies hung with countless stars. Significantly, there is no horizon line in any of these works, making it difficult for us to imagine ‘stepping into’ these environments in the same way we do when we look at a painting such as John Constable’s The Hay Wain (1821), which invites us not only to visually inhabit the Arcadian Suffolk landscape it depicts, but perhaps also to take ownership over it.

What Celmins offers instead is vast, unremitting stretches of sea, sand and sky that feel like they extend far beyond the boundary of the image. These harsh topographies are not the stage for some trivial human drama. Rather, they are thrillingly indifferent to our species’ concerns.

In her print Night Sky 2 (Reversed), Celmins returns once again to the heavens, although here she upends expectations by rendering the stars as black pin pricks, and space not as endless darkness, but as a white expanse of untouched paper. How to interpret this reversal? Thought about in terms of mark making, it has a certain logic. Stars are objects, and these she depicts. Space is (by definition) the absence of objects, and this does not trouble her hand. In the end, perhaps Night Sky 2 (Reversed) is really a work about the limits of human knowledge, or human perception. Perhaps somewhere in our infinite universe there are beings for whom the stars blaze black.

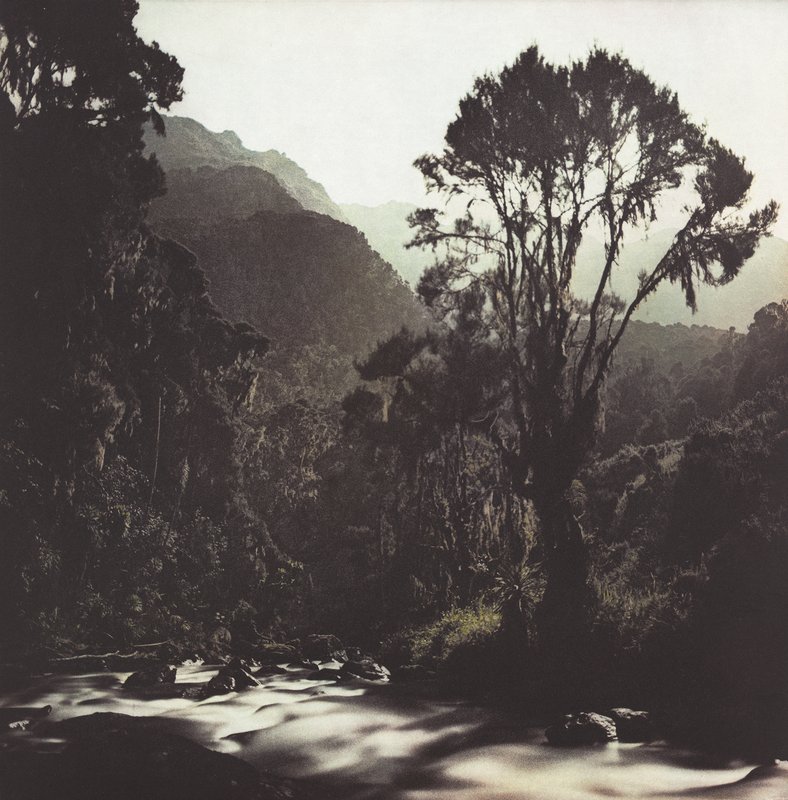

Darren Almond, Fullmoon@Bujuku: Mountains of the Moon (2010)

Works of landscape art are, of course, concerned with place, but might they also be concerned with time? This question is at the heart of Darren Almond’s colour photogravure Fullmoon@Bujuku: Mountains of the Moon (2010). The work depicts the fertile peaks of the Rwenzori Mountains, an ecologically distinctive region of Uganda that went uncharted by early European explorers owing to its geographical remoteness, and the dense fogs that regularly shroud it from the outside world.

Patiently waiting for the skies to clear, the British artist and 2005 Turner Prize nominee photographed this landscape at night using long exposures lasting many minutes, with his only light source the otherworldly glow of the pale and distant moon.

Almond has said that with such exposures, ‘you can never see what you are shooting, but you give the landscape longer to express itself’. Photography, here, is slowed from something urgent to something accretive, even sedimentary. Time becomes not an enemy, but a friend. Note that Almond was only able to make this image with the cooperation of the Rwenzori Mountains’ weather systems, and then only when the moon was at its fullest. This is not a work about humanity’s dominion over the natural world, but about rather about how the landscape and the landscape artist are part of a single continuum.

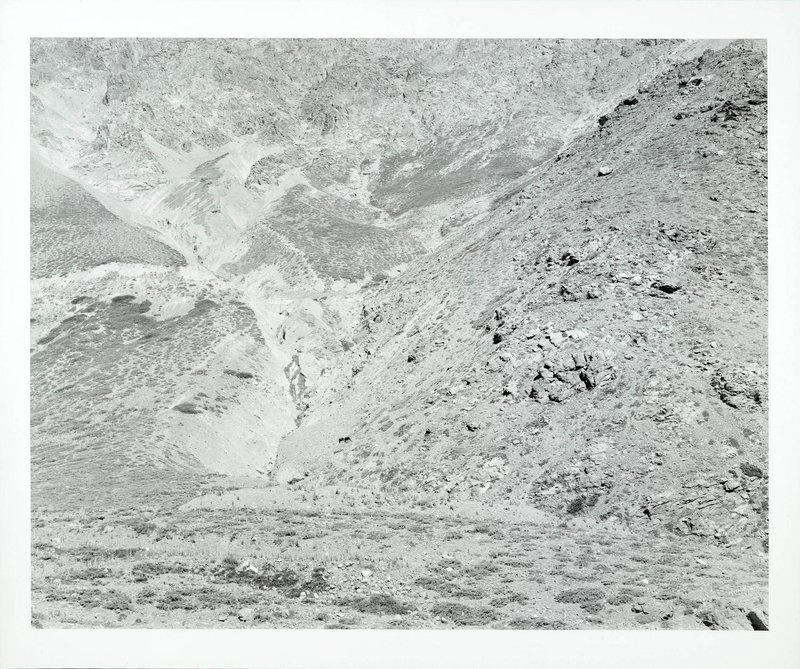

Edward Burtynsky, Carrara Quarry #2 (1993)

To landscape a territory is to give it a particular shape, and few images provide a more dramatic example of this than Edward Burtynsky’s photograph Carrara Quarry #2 (1993). To capture this shot, the leading Canadian photographer travelled to the Carrara quarries in Italy, from where Michelangelo obtained the marble for the works which were to transform European art. The Renaissance master famously observed that: ‘Every block of stone has a statue inside it, and it is the task of the sculptor to discover it’. For Burtynsky, however, it was the gouged surfaces of the quarries’ rock faces that fascinated, which he has said “simultaneously reveal the process of [their] own creation, as well as display the techniques of the quarrymen”.

Carrara Quarry #2 presents us with a landscape that’s been utterly transfigured by human will. What looks like the steps of a vast ziggurat have been carved into this ancient geological formation, their regular cuboid shapes contrasting sharply with the undulating mass of the as-yet unquarried stone. Some sense of the scale of this enterprise is given by the precipitous vehicle tracks, and the red boxes of the buildings that dot the site. Granted this god’s eye view by Burtynsky, it’s hard not to feel like some kind of a creator deity, busy fashioning a world. And yet, this scene is not wholly ours to command. Dark vegetation flourishes among the rubble. Nature, it seems, will always reassert itself.

Paola Pivi, Untitled (Zebras) (2013)

For most of recorded history, human societies knew little about the world beyond their borders, and geography was a discipline that shaded into fantasy. Think of the famous Lenox Globe, which was produced in early 15th Europe, and features the words ‘HIC SVNT DRACONES’ (‘here be dragons’) along the coastline of Eastern Asia, or the legend of Prester John, an entirely fictional figure who medieval scholars claimed ruled over a lost Christian kingdom variously sited in India, Mongolia, and Ethiopia. Today, such beliefs seldom obtain. There is no space for dragons in the age of Google Earth.

The Italian artist Paola Pivi’s photograph Untitled (Zebra’s) (2013) returns us to an era in which the geographical imagination might still take flight. High up on a snow-capped mountain range (in fact, a park in the Italian Alps), we see a pair of zebras nuzzling together for warmth, their striped bodies echoing the black and white of the surrounding peaks. Did some unknown power transport them here from the African savannah, or is this evidence of a previously unknown population of zebras that’s established itself, like Prester John, far from its customary home? Pivi – who was awarded the Golden Lion at 1999 Venice Biennale – provides no answers. Her concern here is rather wonder, humour, and a joyous scrambling of what we think we know.

Sebastião Salgado, Fortress of Solitude, from the series Genesis (2005)

In the world of DC Comics, the Fortress of Solitude is a glittering, icy castle built by Superman on the frozen Arctic tundra. Utterly inhospitable to ordinary humans, it’s the place where the Kryptonian übermensch goes when he wants to be alone. While Superman’s keep is of course fictional, it has something close to a real-world counterpart in the sublime ice formation that features in Sebastião Salgado’s Fortress of Solitude (2005), which the lauded Brazillian photographer shot in the Antarctic as part of Genesis, an eight-year, United Nations-sponsored project to document the few corners of the Earth still untouched by industrialization.

Recalling both the canvases of the 19th century German Romantic painter Casper David Friedrich, and the alien topographies of sci-fi films such as The Empire Strikes Back (1980), the landscape captured by Salgado feels not quite of our time, or perhaps even of our planet. And yet, the fact that Fortress of Solitude is an image of the 21st Century Earth is precisely the photographer’s point. The very fact that he was able to bear witness to this sub-zero fastness – and his photograph of it was so widely circulated – attests to the technological ‘super powers’ we have developed as a species.

These though, often come at a devastating environmental cost. If Salgado’s Fortress is not to melt into the surrounding seas, we will have to learn to treat our planet not as a resource to be exploited, but as our cherished, fragile home.

Allan McCollum, Lands of Shadow and Substance No. 9 (2014)

One function of traditional landscape paintings is to bring the outdoors (or rather a static image of it) indoors. Contemplating, say, a canvas of a sunlit spring meadow hanging on the walls of our home, we might momentarily be transported from our centrally heated sitting room, and forget that outside our windows there’s a storm raging through the dark winter night. What happens, though, when we turn our eyes from the canvas? The spring meadow recedes from our consciousness, and we’re returned to the here and now. The quality of a given work is no guard against this. We could live with a Turner or a Cezanne, and most of the time it’d simply be part of the furniture.

The celebrated American artist Allan McCollum’s print Lands of Shadow and Substance No. 9 turns on the notion of the landscape painting as a (neglected) backdrop. Like the other 26 images in this series, it is based on screen shot of a scene from the television show The Twilight Zone (1959-64) that features a canvas depicting some verdant spot or other. Significantly, these works were not drivers of the horror anthology’s narratives, but rather pieces of set design employed to give a TV sound stage the appearance of a plausible domestic interior, no less ambient than a sideboard or a rug.

Knowing this, paying McCollum’s landscapes our full visual attention becomes a vaguely illicit, even uncanny experience. Does Lands of Shadow and Substance No. 9 transport us to the blurred, black and white woodland it depicts, or to some crepuscular realm – a twilight zone – where distinctions between inside and outside, and reality and artifice, have been hopelessly lost?

[landscapetom-module]

Related stories

What to say about your new Jenny Holzer print (or Skateboard or LED)

Artist Jean-Michel Othoniel on the Artspace works he would buy