For Jean Baudrillard, all the cities of the world were identical. As the postmodern philosopher wrote: “Only one [city] exists, and you are always in the same one. It’s the effect of their permanent revolution, their intense circulation, their instantaneous magnetism”. To a degree, the ever-playful Baudrillard was correct. There is a raw, impatient energy that’s common to urban spaces everywhere, and which pulses through New York and New Delhi, London and Lagos, Sydney and Seoul. And yet, to the relief of tourist boards across the globe, this energy manifests itself in many different ways. Italo Calvino, that great poet of the polis, put it well: “The catalogue of forms is endless: until every shape has found its city, new cities will continue to be born”.

Artists, of course, have long been drawn to urban environments. Witness Éduoard Manet’s paintings of 19th Century Paris, or the work of the luminaries of 1970s New York’s downtown scene, among them Laurie Anderson and Gordon-Matta Clarke. Here – at a time when civic life is adjusting to the age of Covid-19 – we gather together seven visions of the city by a group of international artists, highlighting everything from its role as a seat of government to a site of apocalyptic destruction, its status as a place where heroes (and villains) are memorialized, and whole communities go ignored. What links them is a sense of dynamism, and of transience. The city never stands still for long.

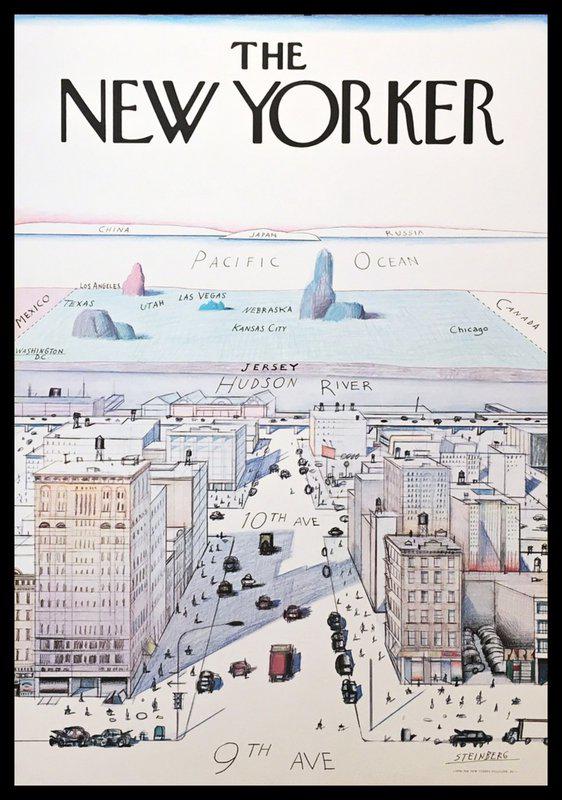

Saul Steinberg, The New Yorker (1976)

“A true New Yorker”, wrote the novelist John Updike, “secretly believes that people living anywhere else have to be, in some sense, kidding”. This credo is very much in evidence in the cartoonist Saul Steinberg ’s iconic cover for the March 29th 1976 edition of The New Yorker, the upmarket magazine to which Updike was a regular contributor. Sometimes titled A Parochial New Yorker’s View of the World, his illustration places the viewer on Manhattan’s 9th Avenue, looking west. While the city’s buildings, cars and pedestrians are rendered in loving detail, once our eyes cross the Hudson river the rest of America becomes a plain blue square, relieved only by a handful of mountains and mesas. Just five other US cities are marked on this territory, as though to indicate Manhattanites’ utter indifference to (or even contempt for) the so-called “flyover states”.

Beyond the waters of the Pacific lay the landmasses of China, Japan and Russia – distant rivals and enemies. Notably, Steinberg puts Europe firmly at the viewer’s back, as though to indicate the passing of the cultural torch from the old world to the new. Europeans, it seems, can keep their Gothic cathedrals and their Renaissance frescoes, their Beethoven and their Shakespeare. Manhattan has the Chrysler building and Abstract Expressionism, bebop and The New Yorker magazine. Is Steinberg poking gentle fun at the inhabitants of the big apple? If so, they’d surely reply with a shrug. For many Manhattanites, New York is (in the words of Truman Capote, another New Yorker contributor) “the only real city-city”. Everywhere else is just a name on vague and near-featureless mental map.

Peter Bialobrzeski, Nail Houses #34 , Shanghai 2013 (2014)

First established as a city in 1291 during the Yuan dynasty, Greater Shanghai is currently home to over 26 million people, a figure that’s roughly equivalent to the combined populations of Sweden, Denmark, Norway and Finland. Constantly expanding, its skyline taking on a different shape with every passing year, this hypermodern Chinese megalopolis appears to have only one direction of travel: forward to the future, at thrilling – and terrifying – speed. And yet, there remain those who do not share this vision of the city. Shanghai’s gleaming new developments are dotted with what are colloquially known as dingzihu, or “nail houses”, older residential properties whose occupants have refused to budge when their homes have been scheduled for demolition by the civic authorities. One such dingzihu is the subject of acclaimed photographer Peter Bialobrzeski ’s shot Nail Houses #34, Shanghai 2013.

The house in this image seems to have once been part of a terraced street. Following the bulldozing of its neighboring properties, it now stands alone, a single chipped incisor in an otherwise toothless gum. For all the building’s shabbiness, though, there are signs that somebody still values it. Potted plants – tiny gestures of rus in urbe – are arranged around the red plastic sheeting that serves as a makeshift wall, and within the dwelling a light gleams bright. While to Shanghai’s city planners this home is nothing but an irritating anachronism, its heart is still beating. We might wonder how long it will be before it inevitably flatlines.

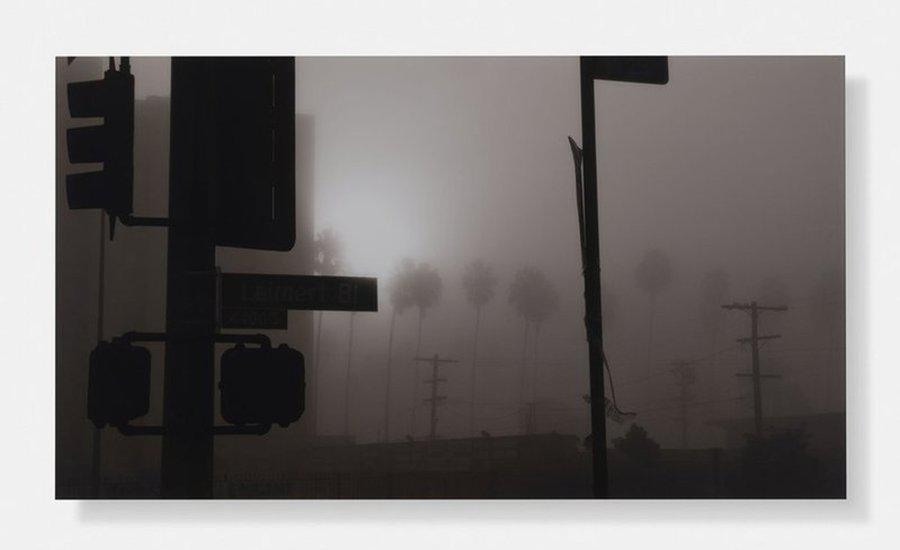

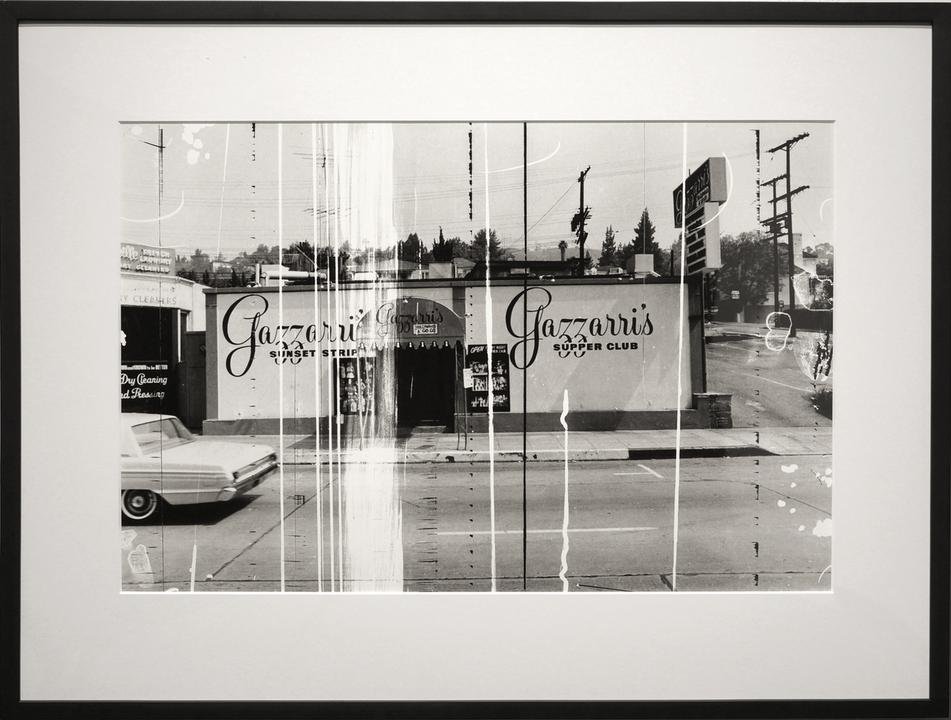

There’s a famous passage in Brett Easton Ellis’ 1985 novel Less Than Zero in which the narrator – a privileged white college student – has a disquieting encounter while driving in his home town of Los Angeles: “I come to a red light, tempted to go through it, then stop once I see a billboard sign that I don’t remember seeing and I look up at it. All it says is ‘Disappear Here’ ”. As we read on, it becomes clear that the words on the billboard are a warning. LA – with its smog, its empty celebrity culture, its many lurid temptations – is a place where someone like the narrator might well self-obliviate.

Shot on an early morning in South Los Angeles, a poor and overwhelmingly Black and Lantinx area of the city, the lauded African American artist

Arthur Jafa

’s photograph LA HAZE I plays, like Ellis’ novel, with the notion of disappearance. In the foreground, traffic lights and street signs are dark silhouettes, communicating only their own outlines. In the background, trees and pylons are shrouded in the ghostly haze of the work’s title. South LA remains an undeserved part of the city, often ignored by Los Angeles’ richer – and whiter – inhabitants. Looking at this image, we might remember the following words, in which Jafa reflects on the challenge of identifying and developing a specifically Black American visual aesthetics: “How do we imagine things that are lost? What kind of legacy can we imagine despite that loss and the absence of things that never were?”

Compared to the world’s great civic plazas – Mexico City’s Placa de la Constitution, say, or Krakow’s Rynek Glowny –Trafalgar Square is something of an embarrassment. Outside of political protests, few self-respecting Londoners tarry long in this unlovely, traffic-strafed spot, preferring to leave it (and its collection of statuary hymning Britain’s bloody imperial past) to bands of bewildered tourists, and flocks of mangy pigeons. Atop its 44 metre-high column at the centre of the square, William Railton’s 1843 statue of Horatio Nelson gazes down not on the beating heart of the nation’s capital, but on coachloads of Leeds United away fans pushing each other into the fountains, and EFL students consulting Googlemaps for directions to the nearest Pret.

Perhaps a redesign is in order. In this print, the iconoclastic British artist Scott King proposes the removal of the famous admiral’s column, bringing his statue if not down to Earth then at least into pedestrians’ line of sight. To a degree, this is a work about Britain’s need to finally confront the fact that it hasn’t been a global super power for the better part of a century, yet it is also one about the strange invisibility of public art in our cities. King might have moved Nelson closer to the ground, but of the scores of people in this image, only a handful are paying the victor of Trafalgar any mind.

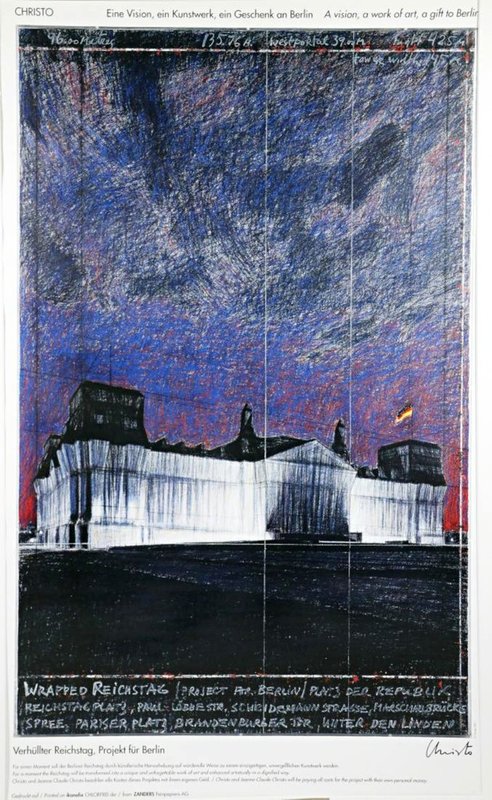

In 1995, following some 24 years of lobbying, the Romanian and French artist duo Christo and Jeanne-Claude finally wrapped Berlin’s Reichstag in 100,000 square metres of silver fabric, fastened with blue rope. An extraordinary technical achievement (which involved one hundred rock climbers abseiling down the building’s façade, in what Christo described as “a kind of aerial ballet”), this work was also celebrated as a profound affirmation of democracy. Opened in 1894 to house the Diet (or deliberative assembly) of the German Empire, it was subject to an arson attack in 1933 that the Nazi party used as a pretext to consolidate its power, and following decades as a near-ruin was identified as the future home of the reunified German Bundestag, or parliament, in 1991, two years after the fall of the Berlin wall. The symbolism of this decision was, in part, spatial: the building is sited a couple of metres from the border that once divided the city into West and East.

Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s audacious intervention came some four years before the official reopening of the Reichstag in 1999, following its reconstruction by the architect Norman Foster. In this offset lithograph poster, we see the building at night, its fabric sheathing glowing with what seems like inner light. At the poster’s top right are the words “A vision, a work of art, a gift to Berlin”. Tearing the paper from a present can lead – like democracy itself – to delight or to disappointment, but what Christo and Jeanne-Claude were concerned with, here, was the moment of anticipation that precedes the act of unwrapping, when anything and everything seems possible.

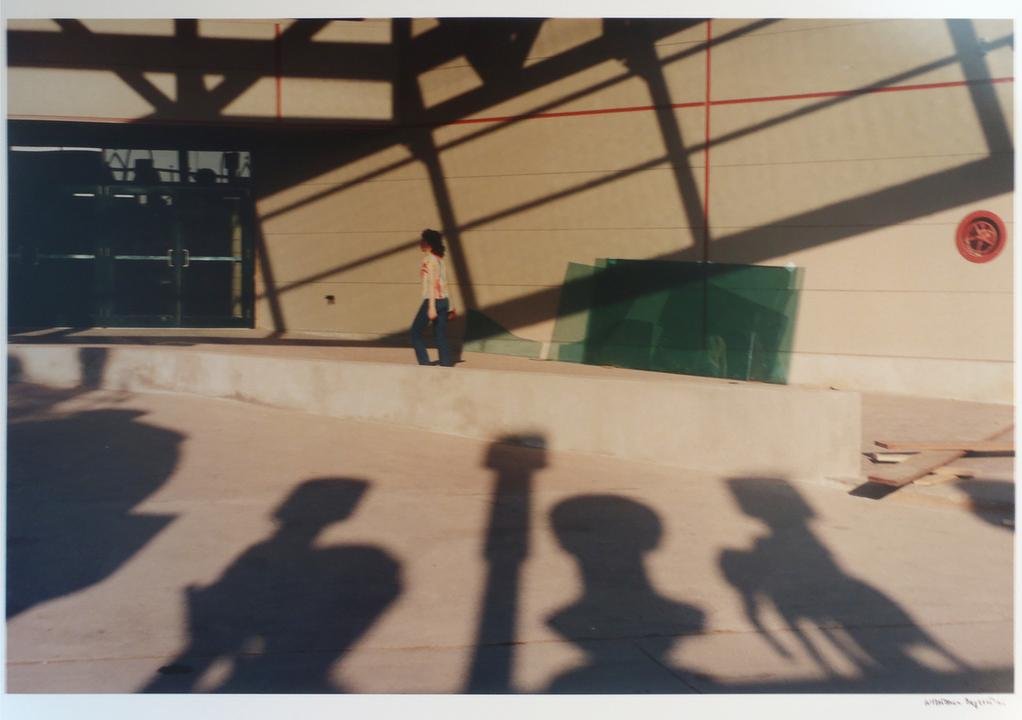

William Eggleston, Atlanta (1983)

A truly seminal figure, William Eggleston is celebrated as a pioneer of colour photography, whose 1976 solo exhibition at MoMA, New York, marked a watershed moment in the history of his medium. The Pulitzer Prize winning writer Eudora Welty has remarked that his “extraordinary, compelling, honest, beautiful and unsparing photographs all have to do with the quality of our lives in the ongoing world: they succeed in showing us the grain of the present, like the cross section of a tree… They focus on the mundane world. But no subject is fuller of implications than the mundane world!”.

In Atlanta, Eggleston trains his lens on a street in the titular American city. A woman strolls along a sidewalk, the red pattern of her top unconsciously echoing the red accents that enliven the façade of the anonymous building to her right. Sheets of green glass, some of them broken, lean against this structure. Perhaps a couple of panes in the door to the left of the image have recently been replaced? In the foreground of the image, shadows of what might be traffic lights or street signs play across the paving, resembling ranked pieces from some vast chess set of alien design. This is not an image of the city as edifice, a place of palaces and parliaments, colossal public sculptures and gleaming corporate HQs. Rather, it’s somewhere that generates fleeting, and strangely beautiful impressions, somewhere that remakes itself day by day, moment by moment, and is always somehow new.

Matthew Day Jackson,

August 6th, 1945

(2009)

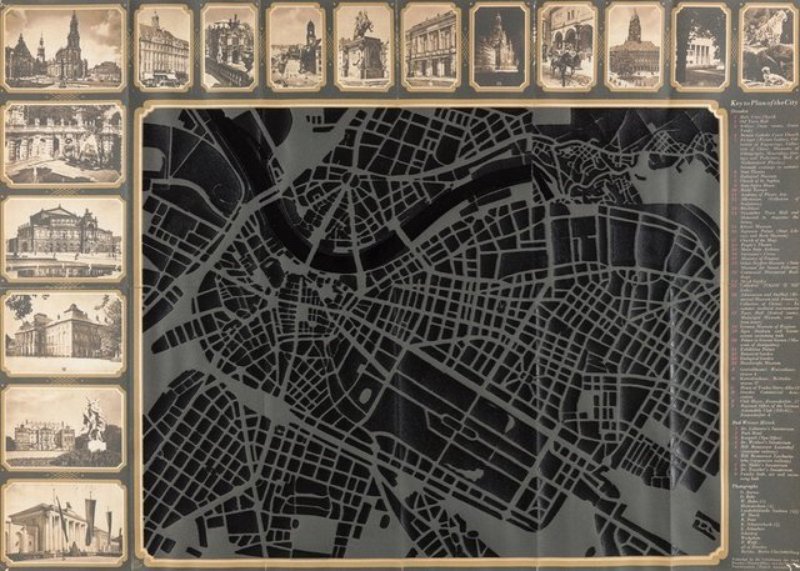

There is an apparent mismatch between the subject of the noted American artist Matthew Day Jackson ’s print (a sepia-toned tourist map of the German town of Dresden, with the streets and buildings burned away, as though by the Allied fire-bombing campaign of February 1945) and its title (which alludes to a date sixth months later, on which the United States detonated an atomic device known as Little Boy over the Japanese city of Hiroshima). To parse this, it perhaps helps to know that Jackson has given this title to several other works depicting topographical views of urban centres bombed in WWII, including London, Hamburg and Gorky/Nizhny Novgorod. Why this scrambling of place and time? And why in, say, his 2017 work August 6, 1945 (Hyde Park) does the British capital look like it’s been attacked not by the Luftwaffe, but by an all-out nuclear assault?

The artist’s answer is that these works are as much about the future as the past. His title, he has said, “perhaps suggests that the bomb that was dropped on Hiroshima had no end and led to the complete burning of the entire globe… Not just one but all of the devices that came forth after Little Boy and Fat Man etc. became one destructive body… All it would take is one destructive device to begin the ultimate endgame”. The German thinker Walter Benjamin once asked “But is not every square inch of our cities the scene of a crime?”. In his August 6th, 1945 works, Jackson imagines this playing out on an apocalyptic scale.

[city-module]