Much of the history of art is the history of images of monarchy. From monumental granite statues of the Pharaoh Rameses II to Mughal-era miniatures of the Akbar the Great, from Hans Holbein’s searching portraits of Henry VIII to Francisco Goya’s slyly satirical canvases of the Spanish Royal Family, from Édouard Manet’s revolutionary series of paintings of The Execution of the Emperor Maximillian (1867-9) to Andy Warhol’s affectless 1970s silkscreens of the Shah of Iran – political and artistic royalty has collided time and again, often to extraordinary effect.

Images of kings and queens no longer occupy the central place they once did in global visual culture. The reason for this is obvious, and worth celebrating: the slow, uneven and always-imperiled spread of democracy. Nevertheless, royalty – that ancient set of unearned privileges, camouflaged by myth and material splendor – has still fascinated a number of 20th and 21st century artists. In this edition of Group Show, we bring together six artworks that address the regal. Touching on fame and fortune, public image and private joy and grief, what unites nearly all of these pieces is, in the end, a perhaps surprising tenderness towards their royal subjects, who are presented not only as abstract figureheads but often also as vulnerable human beings. This is of a piece with a famous observation made by William Shakespeare (and later Stormzy): “Uneasy lies the head that wears the crown”.

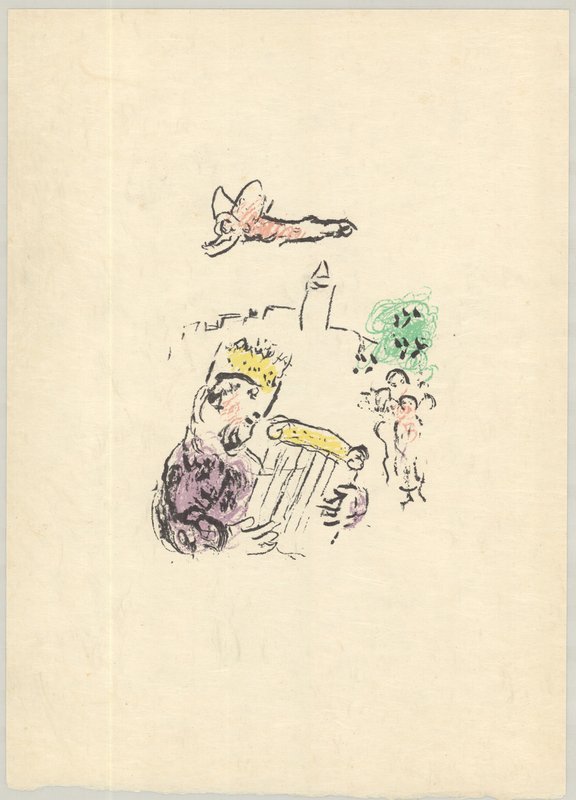

Marc Chagall, King David (pink) (1974)

One of the most celebrated works in all art history, Michelangelo’s marble sculpture David (1501-4) depicts the titular Biblical hero as a naked shepherd boy, about to slay the giant Goliath with the slingshot that drapes over his left shoulder, thus delivering the Jewish people from the threat of the warlike Philistines. This is the kind of origin story that wouldn’t be out of place in a Marvel movie, and sets up David for his subsequent transformation from plucky youth into King of the Israel, and (according to the New Testament Book of Matthew) progenitor of Christ’s family line. Like all great heroes, David was far from one-dimensional. He may have possessed superhuman bravery (and handiness with projectile weaponry), but according to the Old Testament Book of Samuel he was also a musician “skillful in playing the lyre”, who composed a number of the Psalms. When Leonard Cohen sings of “a secret chord / that David played and it pleased the Lord” in his classic track Hallelujah, it’s to this Biblical monarch that he refers.

If Michelangelo’s David is about public duty, then Marc Chagall’s lithograph King David (pink) is about this royal’s inner artistic and spiritual life. Chagall (who the critic Robert Hughes identified as “the quintessential Jewish artist of the 20th century”) depicts the bearded, adult David with his eyes closed, strumming his lyre, so lost in music that he’s oblivious to both his watching subjects, and to the angel that flies overhead, which seems to bend an ear to the sweet melody the king has summoned from his instrument’s strings. Why is this image so oddly moving? Perhaps it’s because we so rarely glimpse our rulers’ creative or devotional hinterlands – the private passions that stir their souls, and make these distant figures feel like relatable human beings.

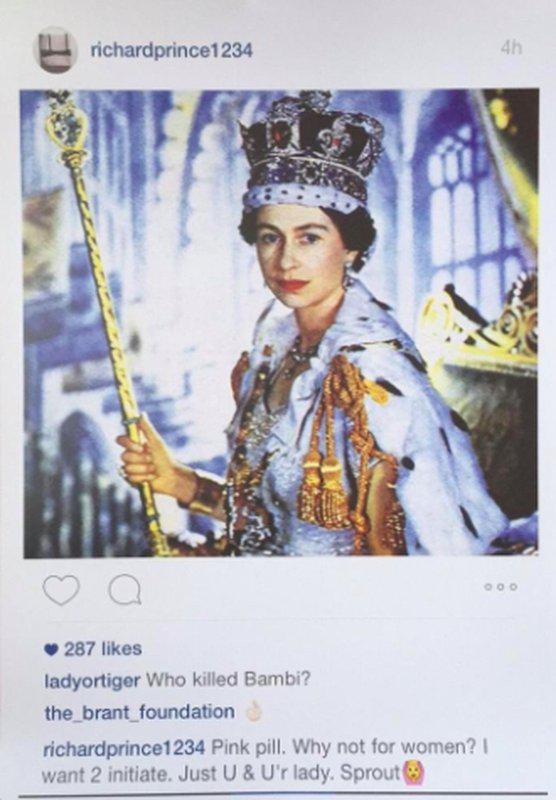

Richard Prince, Instagram New Portraits – Queen Elizabeth II (2015)

Of the 7.8 billion people on Earth, one of the least likely to slide into your Instagram DMs is surely Queen Elizabeth II. Not known, unlike The Duke and Duchess of Sussex, for her devotion to the ‘gram, the British monarch customarily communicates with the wider world through clipped Christmas Day TV broadcasts, and (in the pre-Covid-19 era), public appearances in primary schools, hospitals, and charity headquarters, all of which smell suspiciously of fresh paint. Nevertheless, this print by the lauded American appropriation artist Richard Prince appears to announce Her Majesty’s arrival on social media. In what must surely be a swipe by Prince at how carefully Instagram’s users curate their self-image, the nonagenarian monarch has not posted a selfie, but rather her official coronation portrait, taken in 1953 when she was (a strikingly attractive) 25 years old.

This, of course, is not a screen-grab from the Queen’s account. Look at the user name at the top left of the image, and we see it is “richardprince1234” (a suitably regal name for a man who’s long been considered art world royalty). Why, then, has the artist posted this image? The comments beneath the coronation photo do little to elucidate this decision. The private Brandt art foundation simply offers an OK hand emoji, while another user asks “Who killed Bambi?” (a reference to the death of the doe-eyed Diana, Princess of Wales?), and Prince himself blathers about a “pink pill”, a possible nod to the drug flibanserin, commonly known as “female Viagra”. What Her Majesty would make of all this is anyone’s guess, although it’s likely that she remains strictly old media. Press reports indicate that her favorite TV shows include Dad’s Army, and Last of the Summer Wine.

David Nash, King and Queen (large) (2011)

Monarchy is not humanity’s earliest form of political organization (that would be the family group), but it is an ancient and long-lived institution. Archaeologists are divided on whether Mesopotamia or Egypt gave rise to the first identifiable king, although a current contender is the body of a man found in a tomb in the Egyptian site of Abydos, which has been dated to circa 3320 BCE. Today, 44 of the world’s 195 sovereign states still have a royal head. While most of these monarchies are constitutional, with royals playing a largely symbolic role, absolute monarchy still abides in Brunei, Oman, Qatar and Saudi Arabia. If global political history describes an often-interrupted arc towards democracy, there remains life (and genuine political power) in the concept of kingship yet.

In David Nash’s stenciled work on paper King and Queen, we are presented with a pair of figures, which bear a close resemblance to the acclaimed British artist’s sculptures, which he often hews from living trees using a chainsaw, and blackens with a blowtorch. What’s striking about this royal pair is how difficult they are to historically position. Are they representations of the rulers of some long-lost civilization, or of a future society in which the idea of monarchy has aggressively reasserted itself? Either way, their organic forms, redolent of carved wood, suggest centuries-spanning continuity, the persistence of an ever-branching family tree.

Hung Liu, Untitled (Emperor Yellow) (1998)

One of the first Chinese artists to establish a career in America, Hung Liu’s canvases have been described by the critic and curator Jeff Kelley as an example of “weeping realism” – a reference to both her use of linseed oil washes, and how this painterly device speaks to the blurring of cultural memory, a key concern in her practice. Often working from an archive of late 19th century and early 20th century Chinese photographs, Liu – whose work is in the collections of New York’s Whitney Museum and the Metropolitan Museum of Art – has said that her paintings are an attempt to “give a spirit” to the “forgotten” people in these images, who include anonymous soldiers, sex workers and refugees. In her lithograph Untitled (Emperor Yellow), she focuses on an altogether more prominent figure: Puyi, the Last Emperor of China, who ruled from the ages of two to six between 1908 and his forced abdication in 1912.

Liu’s print is based on a photo of Puyi from 1922, a decade after his reign as a boy Emperor came to an end. This was a key year in his life, which saw him make a failed attempt to escape the Beijing’s Forbidden City (a gilded prison in which he had continued to live following China’s transformation into a Republic), and then later marry the Princess Wanrong (a union reportedly complicated by his homosexuality). Looking at Puyi’s somber, youthful face, we get to thinking of the chaotic life that awaited him: exile in 1924, his crowning as the monarch of the Japanese puppet state of Manchukuo in 1934, his capture by the Red Army in 1945, his subsequent imprisonment and “re-education” by China’s Communist regime, and his final years spent working as a humble gardener. As Shakespeare wrote in Richard II: “You may my glories and my state depose but not my griefs; still am I king of those.”

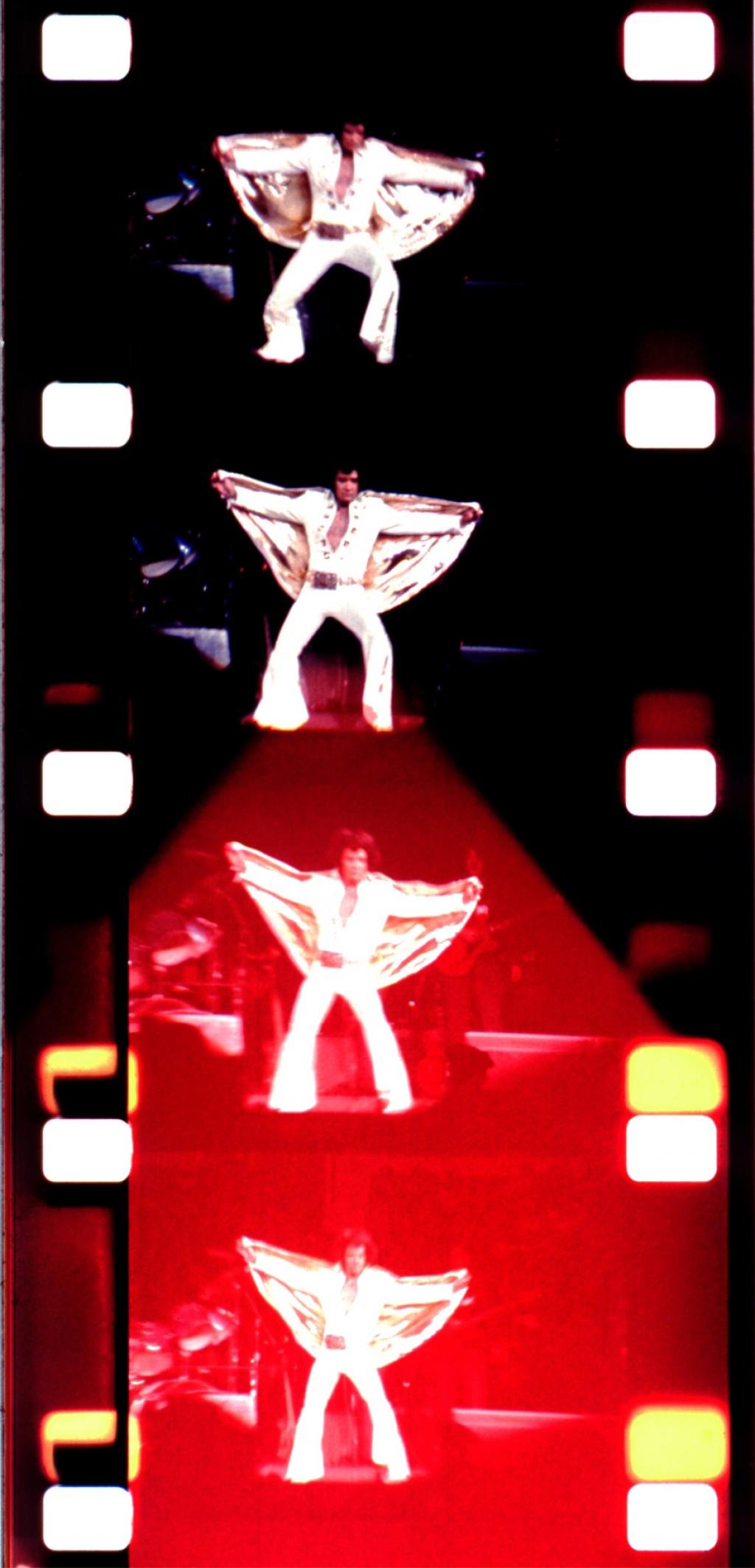

Some kings inherit their crown, others win theirs through war or marriage. Only one has had it bestowed upon them by the Memphis Press-Scimitar, a newspaper that in 1956 called Elvis Presley “the fledgling King of Rock ‘n’ Roll’’, a title that is still associated with the singer in the fifth decade since his death. While there is a persuasive argument that Elvis’ musical legacy amounts to little more than putting a white face on Black cultural achievement (see, for example, Public Enemy’s blistering track Fight the Power, in which Chuck D raps that “Elvis was a hero to most / But he never meant shit to me”), his real innovation was to run with the Press-Scimitar’s plaudit, and self-consciously transform himself into a Tennessee Louis XIV – an early and perhaps still unsurpassed example of pop cultural royalty.

In this work by the seminal, Lithuanian-born American filmmaker Jonas Mekas, we see Elvis give what was to be his last New York concert, five years before his death. Across four frozen film frames, the singer – now on the chubby, druggy, downward slope of his career – raises the arms of his signature white jump suit, his cape forming a pair of angel’s wings, a devilish red light blazing behind him. We might think of this work as a contemporary take on Peter Paul Ruben’s painting The Apotheosis of James I (1632-4). There, a British monarch is lifted up to heaven by a flurry of cherubim and seraphim. In Mekas’ film strip, an all-American King seems as though he is about to be dragged into hell.

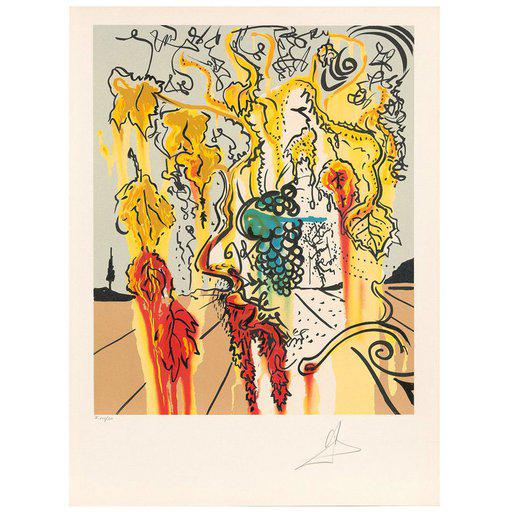

Banksy, Di-faced Tenner (2004)

Minted in the Kingdom of Lydia (now part of modern-day Turkey) in around 600BC, the Lydian Lion is the world’s oldest coin, and takes its name from the leonine royal symbol with which it is stamped. In the centuries since, monarchs the world over have marked their territory’s currency with both their heraldic devices, and their portrait. The logic of this was simple: if money is power, then having one’s own visage on a nation’s money is power of a singular sort. And then there’s the fact that coinage and (later) paper notes provided a unique promotional opportunity. After all, they are carried in every purse and pocket in the realm.

In Banksy’s offset lithograph Di-faced Tenner, the infamous British street artist takes a £10 banknote, and replaces the customary likeness of Elizabeth II with one of the late Diana, Princess of Wales. On one level, this is a bluntly obvious act of subversion: the ageing Queen of England has been swapped out for the deceased, yet forever youthful ‘Queen of Hearts’, a figure who so far has come closer than any other to bringing the House of Windsor crashing down. And yet, Banksy’s Di-faced Tenner is also a subtle meditation on the circulation of images in our hypermodern age. Consider the expression on Diana’s face, the way her eyes look up to her left, as though she’s longing to escape to another representational context – a newspaper spread, perhaps, or a magazine page, or a TV documentary. This media landscape – as much a presence in British daily life as a £10 note – was what gave the Princess an alternative power base to that of her mother in law. In the end, of course, it would also be implicated in her tragic and untimely death.