Gifts can be complex things. The gold, frankincense and myrrh presented to the infant Jesus by the Biblical wise men – an event depicted in Sandro Boticelli’s painting The Adoration of the Magi (1475) – might have been suitably flashy offerings for the Son of the Almighty, but they also foretold his future kingship, ministry, and eventual death. Likewise, the wooden stallion given to the besieged city of Troy by the departing Greeks in Homer’s Iliad – the subject of Giovani Domenico Tiepolo’s monumental canvas The Building of the Trojan Horse (1760) – was not quite what it first seemed. Then we might consider the potlach feasts held by the indigenous people of the Pacific Northwest coast, analyzed by Marcel Mauss in his influential anthropological study, The Gift (1925). Among these communities, social bonds were cemented through ritual acts of giving, with the highest status accorded not to those who received the most booty, but to those who gave the most away.

To give, of course, is not merely a matter of handing over an Amazon parcel. We might give thanks, we might give our time, or our attention, or even – like the drowned figure of a young woman in Paul Delaroche’s celebrated painting The Young Martyr (1855) – our lives.

As Christmas nears, we bring together six works that probe the knotty notion of giving. They are not what might be considered traditional festive fare, but one of them might make the perfect present for somebody close to your heart.

Lydia Blakeley - Charities (2019)

In his Epistle to the Corinthians 1:13, St. Paul famously writes: “Now abideth faith, hope, and charity, these three; but the greatest of these is charity”. For the Apostle, this last word had nothing to do with salving his vague guilt at his own good fortune by dropping a few coins in a Red Cross box, or reducing his tax liability by donating a painting to a museum. Rather, it was an impulse inspired by what the Classical Greeks called ‘agape’, or unconditional love for one’s fellow human beings.

The emerging British painter Lydia Blakeley’s canvas Charities, depicts three young women, who from their pastel dresses and frou-frou fascinators appear to be guests at a wedding (a ceremony, we should note, at which Corinthians 1:13 is a popular choice of reading, due to a widespread misconception that it addresses romantic love). A happy occasion, then, but for the fact that one of the trio has suffered an unknown upset. Head bowed, shoes shucked off, she sits weeping on the grass, comforted by her friends, who stroke her bent back, offer her water, and examine her mobile phone screen, which seems to be the cause of this whole sorry affair. In a high-wire act that combines the affectlessness of photorealist painting with the melodrama of scripted reality TV, Blakeley presents us with an image of solidarity, of sisterhood, of giving, and of love.

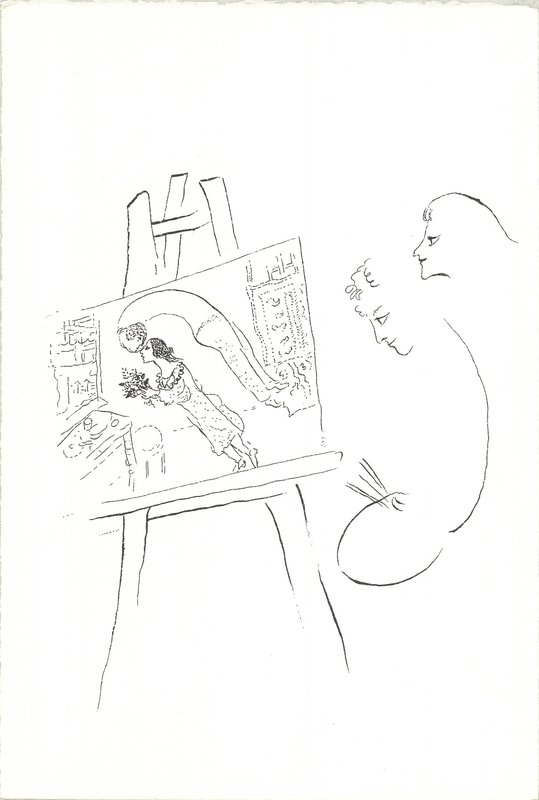

Marc Chagall - The Birthday (1999)

For the novelist, art theorist and French Minister for Cultural Affairs André Malraux, Marc Chagall was “the greatest image-maker” of the 20th century. One reason for this was the Belarusian Jewish artist’s generosity of spirit. As Malraux put it: “He has looked at our world with the light of freedom, and seen it with the colours of love”. In this serigraph, which was printed after Chagall’s death in 1985, he employs a sinuous, featherlight line to summon up a characteristically ardent scene. Palette in hand, a painter (Chagall himself?), shows a young woman a canvas in his studio, depicting a pair of lovers. So enraptured is the male figure in this image that he floats free of the bounds of gravity, twisting his neck at an impossible angle so that he might kiss the sloping bridge of his sweetheart’s nose.

Given that Chagall titled this work The Birthday, we’re surely intended to read the canvas as a gift, which the painter is bestowing on the young woman. Is this an image of his love for her – an emotion so powerful that it sweeps him off his feet? If so, perhaps what is really being gifted, here, is not an artwork, but rather an unguarded glimpse into his soul. Note how the levitating figure has no arms, making self-protection difficult, and the act of painting nigh-on impossible. This, then, is no macho avant-garde artist-hero, whose brush doubles as a sword or penis, but rather a vulnerable human being, who nevertheless opens himself up to potential heartbreak. No wonder Malraux thought Chagall so exceptional.

It’s hard to think of a greater sacrifice than the giving of one’s own life, especially in the cause of something so abstract as a nation state. This is why the poet Horace urged Rome’s young legionnaires on to battle with the words “How sweet and fitting it is to die for one’s country” (a line Wilfred Owen called “the old lie” in his own WWI-era poem, Dulce et Decorum Est), and why today many of us greet active military personnel and veterans with a somber “Thank you for your service”.

In this diptych, the acclaimed Israeli artist Nir Hod presents us with a pair of young soldiers, one male, one female, wearing nothing but green caps on their heads and dog tags around their necks (an omen, perhaps, of their impending death, given that these metal pendants are used to identify the bodies of battlefield casualties). Like supermodels on a Photoshopped magazine page, or marble statues of the Greek martial god and goddess Ares and Nike, they have a hyperreal quality. Surely their perfect, glowing bodies – nude and unprotected as they are – could not possibly be damaged by something so ugly and prosaic as a bullet? And yet, we know from humanity’s long history of brutal, bloody war that the lives of young people like this are given every day, often for the most senseless of reasons. They might be venerated as fallen heroes, or even (as Nir suggests) become objects of a creepy erotic fascination. Nothing, however, will bring them back.

Jeremy Deller - Thank God for Immigrants (2020)

The Roman Catholic tradition divides prayers to God into four main types: adoration, contrition, supplication and thanksgiving. It’s to the last of these categories that this print by the Turner Prize winning British artist Jeremy Deller belongs. Made in response to the Coronavirus crisis, and first sold to support the charities Refugee Action and the Trussel Trust (a network of UK foodbanks), the piece is rooted, as Deller has said, in “seeing the photographs of the doctors and nurses who have died [during the pandemic, many of whom came] from immigrant backgrounds. These are also the people left on the streets who are doing the jobs nobody else is doing: making deliveries and stacking supermarket shelves. This situation is going to reconfigure how we view immigration but also class and wealth and your value in society”.

Let’s offer up a prayer of supplication that Deller is right. For now, the words “Thank God For Immigrants” – picked out in a blocky black font against a rainbow gradient background – are at the very least a welcome contrast to the anti-immigrant messaging that has appeared in the UK public sphere in recent years, from the Home Office’s infamous vans bearing the words “In the UK illegally? GO HOME OR FACE ARREST” to the UKIP part’s poster campaigns during the 2016 Brexit referendum, which – staggeringly – took their visual cues from Nazi propaganda films. Significantly, Deller’s print is designed to be displayed not on a wall, but in a window facing out on to the street. It is, he has said, “a public art work”, and one that recognises that it is generosity and gratitude that will help build a better tomorrow, not miserliness and mistrust.

Trenton Doyle Hancock - Give Me My Flowers While I Yet Live (2012)

Attending one’s own funeral is a macabre – but surprisingly not uncommon – human fantasy. Passing unseen among the tombstones, we hear the eulogy, smell the lilies, watch the tears glisten on the mourners’ cheeks, and satisfy ourselves that we will be missed. This, of course, is impossible, which is why the classic gospel song Give Me My Flowers While I Yet Live pleads: “Speak kind words to me / while I can hear them / so I can hear / the comfort that they bring”.

In this lithograph, the lauded Black American artist Trenton Doyle Hancock – whose stepfather was a Church minister in Paris, Texas – takes the song’s title and prints it over an Henri Matisse-like floral motif, once forward and once in reverse. The resulting mirrored text and botanical imagery bears a marked resemblance to the symmetrical inkblots used by psychologists in Rorschach Tests. What suppressed traumas, then, might this work help us to recover? The answer is surely the inevitable fact of our own death, and that of every other living thing on Earth. Time to hand out our tributes – floral or otherwise – while we still can.

Lawrence Weiner - Give & Get (2014)

“The only art I’m interested in is the art I don’t understand right away”. So says the seminal American Conceptualist Lawrence Weiner, who since the 1960s has eschewed traditional modes of artistic production in favour of utilising language as a “sculptural material” in his radically uncompromising text-based works. These range from written instructions (such as his improbable 1969 edict THE JOINING OF FRANCE GERMANY AND SWITZERLAND BY ROPE, which for Weiner did not need to be enacted in order for it to function as a completed piece) to epigrammatic sentences stenciled directly on to a wall (see his 2005 WITHIN A REALM OF RELATIVE FORM, which speaks not only of its own position in our infinite universe, but also that of everything else that has been and will be).

Resembling an embroidery sampler, this work by Weiner links two sentences – “Give & Get” and “Have & Take” – through a pair of interlocking ampersands. Bar his use of contrasting colours, the graphic treatment of each sentence is identical, and it takes us a moment to realize how very different they are: while the first hints at the redistribution of resources, the second might be read as a hoarder’s charter. Is this a work about rival political philosophies? The American artist has, after all, blazoned one in Democrat blue, and the other in Republican red. Or might it be a meditation on the transaction between Weiner and the anonymous viewer, a figure he characterizes as “the receiver”? When we “give” of ourselves to his works – when we put in the intellectual hard yards and finally “get” them – they become, in a sense, ours. As the artist has said: “Once you know about a work of mine you own it. There’s no way I can climb inside somebody’s head and remove it”.