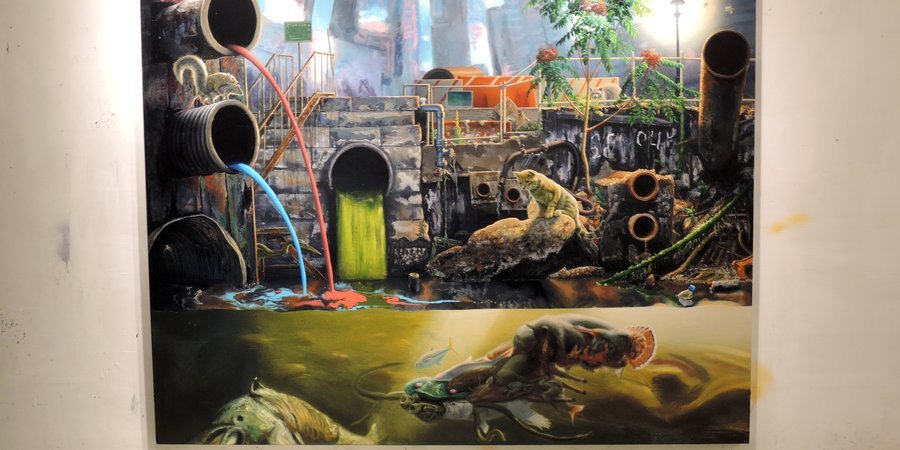

Alexis Rockman is a painter of eco-dystopias, no-man’s lands, and other wild vistas that have been beaten down and broken open. Employing an amalgam of traditional Color Field and Hudson River School painting techniques, Rockman tenderly renders—and simultaneously ravages—lush landscapes with the markings of mankind's destructive footprint, including occasional appearances by deformed fish, genetically-modified crops, and rat infestations.

On September 17, Rockman will debut "Rubicon" at Sperone Westwater,a new series of watercolors and two monumental paintings, one of a radioactive cesspool modeled after Brooklyn’s Gowanus Canal, and one a bloody tableau of animal anarchy at the Bronx Zoo. Later this month, another Rockman exhibition will open at The Drawing Center, on September 27, to showcase the watercolors that director Ang Lee used as the visual inspiration for his 2012 film Life of Pi.

Knowing that you're a native New Yorker with a long-standing interest in environmental conservation, I’m almost surprised it took you this long to take on the Gowanus Canal, which, given its Superfund status as a toxic waste zone, seems like a natural subject for you.

Well, sometimes you have to go far and wide to come home. I love the idea that the places that are right on your doorstep often don’t get that much attention. I don’t think people really consider the Gowanus Canal, that it's a place of wonder, a place of interest. I’ve always been attracted to the things that are doing less-than-well, and the Gowanus is the benchmark of how low you can go. It’s ground zero for its notoriousness. You can say "Gowanus" and that means Superfund—even the word sounds toxic.

Why did you choose to pair these two sites—the Gowanus Canal and the Bronx Zoo—in the Sperone Westwater show?

These two places were really resonant to me as a kid. They are places of abject negligence and intense care. I have mixed feelings about the zoo. I would go there with a sense of wonder, but I was also so worried about what would happen to the animals in the future because I knew that humans were a terrible force. I grew up thinking about scenarios like Soylent Green and Planet of the Apes.

There's a very worrisome beast lurking at the bottom of the canal in the Gowanus painting.

It's a composite creature made out of animals that used to live in the canal. It's sort of the ghost of the Gowanus Canal in the shape of a catfish. When I worked on Life of Pi I became obsessed with composite creatures and this whole tradition in Indian miniature paintings of a big creature made out of little creatures. Here the animal is comprised of a diamondback terrapin, a black bear, a manatee, an American turkey, a red fox, a harbor seal, and so on. The painting was really inspired by that dolphin that swam into the canal last year and proceeded to die. I was sad, and then thought, "How many things have died there over the years?"

You often consult with biologists, climatologists, and other scientists in order to accurately represent realistic ecological scenarios. What has their response to your work been like?

What do they get out of it? They're very generous and I’m thrilled that they give me the time of day. I can’t answer for them, but my guess is that they get a lot of pleasure out of seeing someone they have an affinity to—me—tell a story about what they love and care about that can be blunt and not necessarily be in the language of scientific text. They have to use the language of science; I can use the language of metaphor and I can be very blunt and subjective and say something like, "the future of conservation is bleak and fucked up." There’s no scientist who studies conservation who doesn’t feel that way, but they can’t say so for many reasons. So I can say things that they can't really get away with in public.

Did you speak with any scientists for this new series?

John Waldman, a professor who wrote a wonderful book called Heartbeats in the Muck, which is kind of my bible, and Chris Bowser, who works at Cornell. These guys are so generous and fun and they said, "All roads lead to the Gowanus."

Do you consider yourself an activist?

Absolutely. But it’s an interesting challenge to be alone in a room and be an activist. But I’d like to see things change and I’d like to make paintings that have some sort of momentum. I try.

It seems like human beings have been disappearing from your work. Have you noticed this?

People are so pervasive and these are such human-induced landscapes that it seemed redundant. What would humans be doing that would make it interesting?

Did you have an interest in animation or digital design before you began working onLife of Pi? Is that something you would pursue again?

When I was a kid I wanted to do animation. But being a painter is such an fantastic job. If you know the world of dealing with corporate money, it’s so traumatizing. There’s huge payoff with a project like this, but the struggle to make it is so enormous. I don’t want the headache or responsibility of being the director. I’m so thrilled to be in a room alone every day.

Some might see traces of Dalí or Bosch in your work. Who do you consider your influences?

Everything. I mean, Goya, Mark Dion, who has been one of my best friends for years. Bosch and Dalí are both artists I love, but they have profoundly different takes on the world than I do, other than that the work is pretty psychedelic looking. Bosch had this idea about religion, and so his paintings are cautionary tales of medievalist ideas of the future and the afterlife. And the world is a weird and frightening place in my work and Dalí's, but mine is based on ideas of science. It doesn’t just privilege the subjective. It uses subjectivity informed by history to create this hybrid language. I want it to be almost impossible to look at and impossible not to look at.

But artists like Dalí have faced heightened criticism in the decades since abstraction took hold. Do you feel any of that anti-realist pressure on your work?

I think Dalí suffered from a Warholian thing, from selling himself short as a celebrity late in life. He made a lot of terrible, uneven work over the years and acted silly. I guess that catches up with him, but I think Dalí is as great a painter as any artist. I mean, Renoir and Chagall? What the hell have they done compared to Dalí? Chagall is a bum as far as I’m concerned. As far as as the Clement Greenberg idea of modernism goes, I dealt with that hangover in the 1980s. I think the idea for me to be radical was to paint the damn thing and make it look like a Dutch still life. That was a radical move when I was in school. That was a point of shame for most artists, and I was like, "Fuck you, I’m going to make every glistening highlight on that dragonfly’s wing kick ass.' I want that mosquito to give you the creeps, viscerally.