Stephen Shore is heralded as one of the most important photographers of his generation for his pioneering use of color photography in to capture the beauty and banality of everyday American life. One might be surprised, however, to learn that Shore's subtle distillations of the ordinary world was in part inspired by the always over-the-top Pop art prankster Andy Warhol . It all started when 17-year-old Shore approached Warhol with his camera in hand, asking to photograph the goings-on around the Factory —and Warhol obliged.

In this essay excerpted from Phaidon 's new Factory: Andy Warhol , Shore recalls his time spent photographing the eccentric artists and personalities that came and went at the now-legendary Factory, reflecting on his youthful observations, his private conversations with Warhol, and how his time spent around the cultural icon influenced the decisions he’s made over the rest of his career.

To see a selection of rare photos from this period (and some fascinating anecdotes from the larger-than-life characters that populated it), click here ; click here to purchase the whole book for your library.

When I was five, I was interested in chemistry, and an uncle who was an engineer gave me a darkroom set for my sixth birthday. I wasn’t interested in taking pictures then. I got my first 35mm camera later, when I was eight or nine. First I developed and printed my family’s snapshots—Kodak Brownie pictures. I remember one of those early prints, of my cousin and myself. I printed it inside a heart shape. I’d cut a mask out, I assume from shirt cardboard. A heart shape.

I became very involved in photography early. By the time I was fourteen, I called up Edward Steichen at the Museum of Modern Art and asked for an appointment, and got one. I remember going in, meeting the man; he looked at my pictures. I had a copy of a book the Modern published, Steichen the Photographer , and he autographed it for me. I still have it. He was already very old. He bought three of my prints for the Modern—one was of three boys pointing at something; one was of an iceman delivering ice, with a barrel; and the third was a picture of a boy sitting on a bench in the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

By the time I was seventeen, I was making 16mm films. In my senior year of high school—Columbia Grammar—I simply dropped out. And I met Andy at Jonas Mekas ’s Film-Makers’ Coop, where I showed a film called Elevator . It pictures the inside of a cage elevator, so it’s actually more visually interesting than you might imagine an elevator in an office building to be.

By 1965 Andy was well known in New York cultural circles. I asked him if I could come and photograph at the Factory. He said, “Well, we’re going to Paris tomorrow, but we’ll call you when we get back.” He was perfectly friendly, but there was a dreamy vagueness in his manner, and I didn’t know if I’d ever get a call. Then, really a month later, I did. It was Andy saying, “We’re filming at a restaurant called L’Avventura; do you want to come and take pictures?”

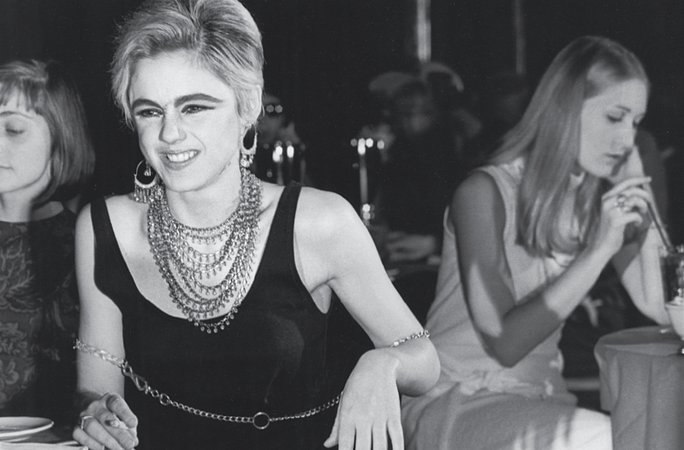

From Shore’s first shoot at L’Avventura: Ann Reynolds, Edie Sedgwick, and Alexandra (Sandy) Kirkland in

Restaurant

(1965)

From Shore’s first shoot at L’Avventura: Ann Reynolds, Edie Sedgwick, and Alexandra (Sandy) Kirkland in

Restaurant

(1965)

I walked right into the filming. My memory is based on the pictures I shot, but I wouldn’t be surprised if people like Donald Lyons and Ed Hennessy were there. Chuck Wein, who was a moving force in Andy’s films then. Edie Sedgwick. Ann Reynolds. Gordon Baldwin. Gerard Malanga. The film wound up being called Restaurant .

Andy would do films almost every week. They weren’t really scripted. Andy would be behind the camera. Chuck would be saying to Edie, “Why don’t you talk about . . . ” That was it.

For a while, I went to the Factory every day. I had a sheet of seamless paper, a fairly good size. They let me keep it up. I’d photograph different people as they came through. Then I stopped going every day and returned only when something new was happening—when Paul Morrissey came, when some new person arrived to be in the films, when the Velvets came. I was going enough so that I would be aware when something new and interesting was happening. I don’t recall feeling uncomfortable the first time I went to L’Avventura. Or the Factory. The space was oblong; it was painted silver. Some areas were covered in foil, which was the work of Billy Linich, later to be known as Billy Name.

Andy would work all the time. There’d be some people helping him, like Gerard Malanga, who would be actively involved in silk-screening whatever the project was. There’d be other people who would just come and hang out. I remember being very impressed, or unfavorably impressed, with some of these people who’d sit on a chair or couch, sit there for hours, doing nothing, waiting for the evening when we went to parties.

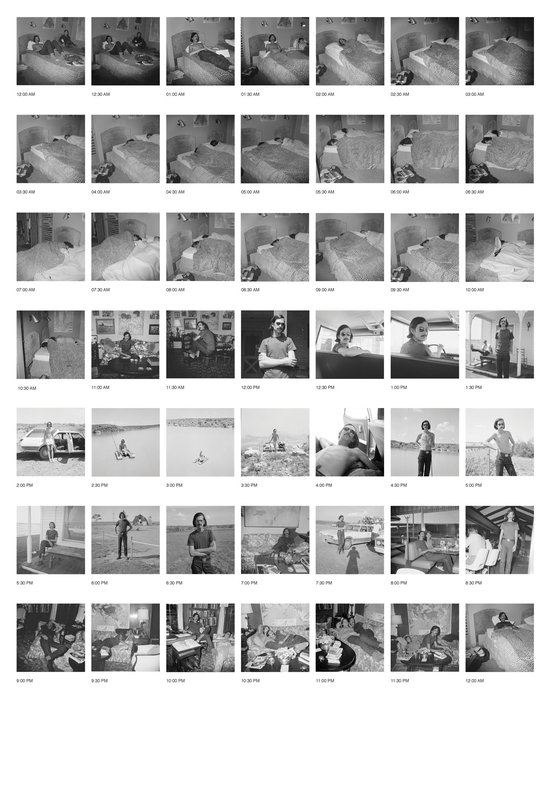

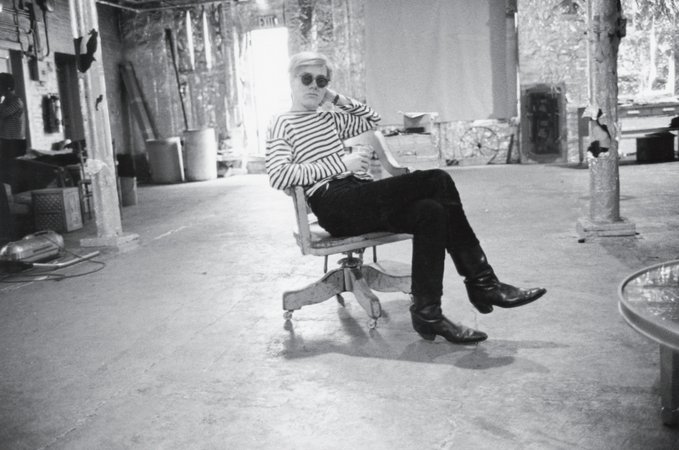

Andy Warhol's Factory

Andy Warhol's Factory

I’d be taking pictures. I would socialize with some of the people. I became especially friendly with Billy Name. He had a kind of a workstation where he sat, kept his records, did his speed, which was the prevalent drug at the Factory. He had a turntable and played opera. We shared a love of classical music.

But the people just hanging out would bother Andy. Every now and then, there would be a sign by the elevator, so when you entered you would see it, “If you have no business to conduct here, please don’t come.” Andy would never enforce it.

Andy came across as very insecure and would ask people what they thought of what he was doing. Although one always had a sense he knew just what he was doing. My guess is that if it really bothered him that people were around, he would stop them, just lock the door. My guess is that it helped him in his work to have people around, to have these other activities around him. I think he kept people involved by asking, “What do you think of this? Oh, I don’t know what color to use. What color should I use?” Just something to keep the swirl of activity around him.

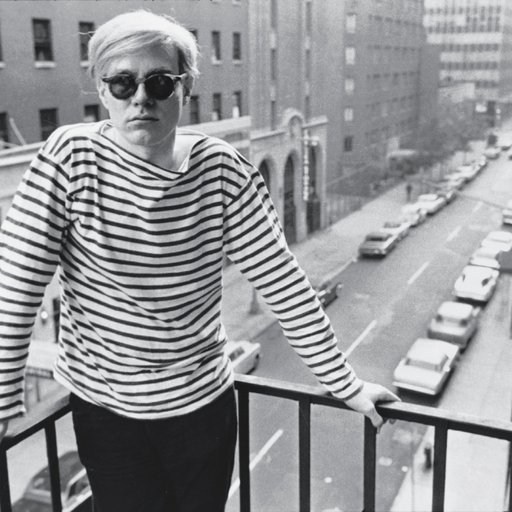

Andy Warhol by Stephen Shore

Andy Warhol by Stephen Shore

I was the only person of the people who were hanging out with him, or one of the few, who lived uptown. Often we would wind up, say, in Chinatown at 2 a.m. and share a cab home. We’d have conversations. He was very open and unaffected. He would say things he wouldn’t have said in a more public situation. One time Andy asked me if I had seen some film on the Late, Late Show the previous night. I forget the film, but Priscilla Lane was in it. A 1930s tearjerker.

And, in fact, I had. Andy wanted to know what the ending was, because he said he started crying and fell asleep. Then he said, “And the television was off in the morning, so I guess my mother must have come in and turned it off.” He never talked about his mother. She was just mentioned as a part of his life, like, I woke up and the television was off, so I guess my mother turned it off. He never said anything reflective about her. But I remember, at the time, finding it stunning and poignant that he’s Andy Warhol, who’s just come from some all night party or several of them, and has turned on the television and cried himself to sleep to a Priscilla Lane film, and his mother had come in and turned it off.

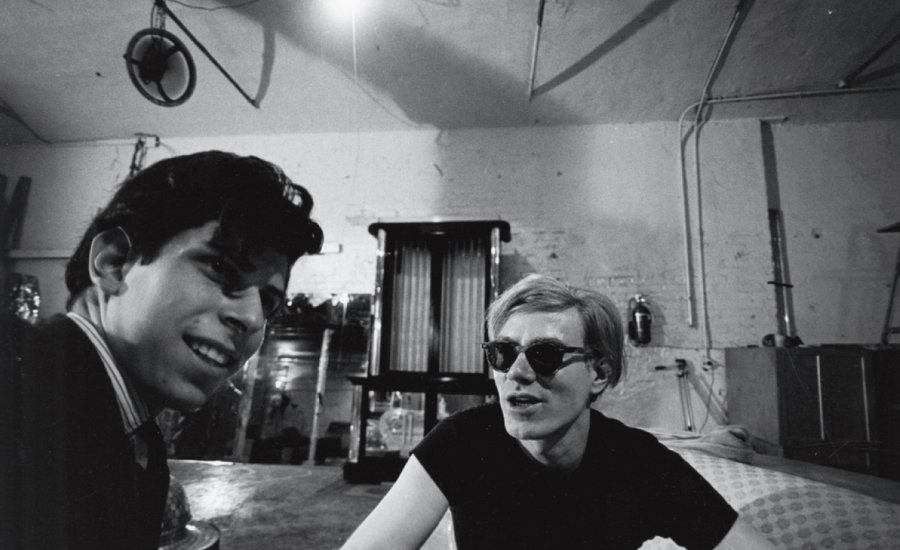

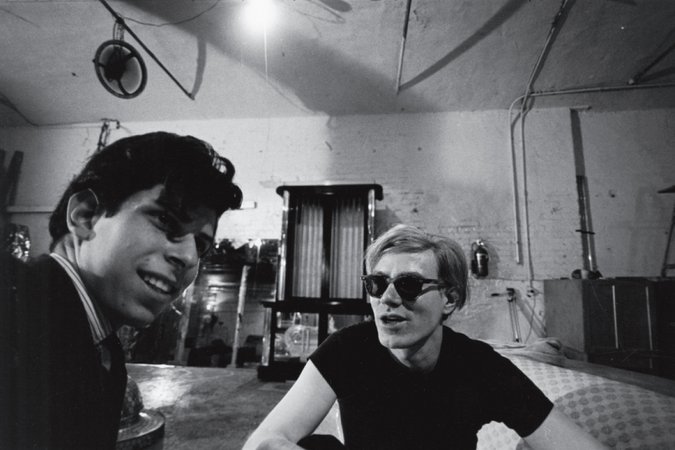

Stephen Shore and Andy Warhol

Stephen Shore and Andy Warhol

I remember another conversation. During or just after the filming of The Chelsea Girls , sometime in 1966, Andy started talking about, “My films are so boring.” What Jonas Mekas was really first promoting were films like Sleep , Eat , Empire — Empire was eight hours of the Empire State Building, which I’d seen and actually sat through most of. At the time, people were writing about the nature of boredom in his films. The films were kind of moving paintings or paintings in time, in a way. Eat was a camera held steady as Robert Indiana eats a mushroom. Films like The Chelsea Girls were more narrative, dealing with personalities. Coming from a knowledge of his earlier films, I was impressed, interested, that he was complaining about how boring those earlier films were. Then Andy said, “But I don’t know how to make them more interesting, and that’s why I want to have two screens”— The Chelsea Girls has two screens. He said, “I don’t know how to edit. So I thought if I had two screens, there’d just be more to look at and people wouldn’t be so bored.” He’d never edited. The way he would do scenes—each scene of a longer film, like My Hustler , was a reel of film. A scene on the beach, a scene in the bathroom—a reel. Then he did two screens at once, so there’d be more happening.

I’d been doing photography for a long time by that point, but I had always done it in an untutored way. For reasons of my youth, and reasons of the lack of intensity of critical discourse around photography at that time, I think I was still very naïve. I saw Andy making aesthetic decisions; it wasn’t anything he ever said to me. I saw these decisions happening over and over again. It awakened my sense of aesthetic thought. It had to do more with the framework that the work was seen in. Like the nature of serial imagery, which his work deals with, obviously. I began to think about it and was involved, to some extent, in a little way. More in sequence than seriality. I think I learned by observing, not observing him in order to learn, just by being exposed to the decisions and the actions he was making. More basic was simply a transition to thinking aesthetically. By the end of my stay at the Factory, I found that just my contact with, and observation of, Andy led me to think differently about my function as an artist. I became more aware of what I was doing.