In her wonderful book The Artist’s Joke, the critic Jennifer Higgie observes that “Somewhat ironically it seems that humor [in art] has not been considered a subject worthy of serious consideration, despite the fact that – quite apart from making us laugh – it has been employed to activate repressed impulses, embody alienation or displacement, disrupt convention, and to explore power relations in terms of gender, sexuality, class, taste, or racial and cultural identities”.

Laughter, in short, is not merely a matter of throwaway gags. Indeed, it has been central to the cultural politics of movements including Dada, Surrealism, Situationism, Fluxus, Performance and Feminism, as well as the practices of countless artists who defy easy categorization. This focus on humor is unsurprising: after all, it is what makes the good times speed by, and what helps us to endure the slow grind of the bad. As the novelist Mark Twain wrote: “The human race has one effective weapon, and that is laughter. The moment it arises, all your irritations and resentments slip away and the sunny spirit takes their place”.

Here, we gather together work by six noted contemporary artists that make with the funnies. While the subjects they engage with are often very far from inherently hilarious – from body taboos to power elites, from crimes against humanity to the philosophical problem of “other minds” – their wit, wisdom and lightness of touch is a Twain-ian balm for the soul.

DAVID SHRIGLEY -

Look at This

(2020)

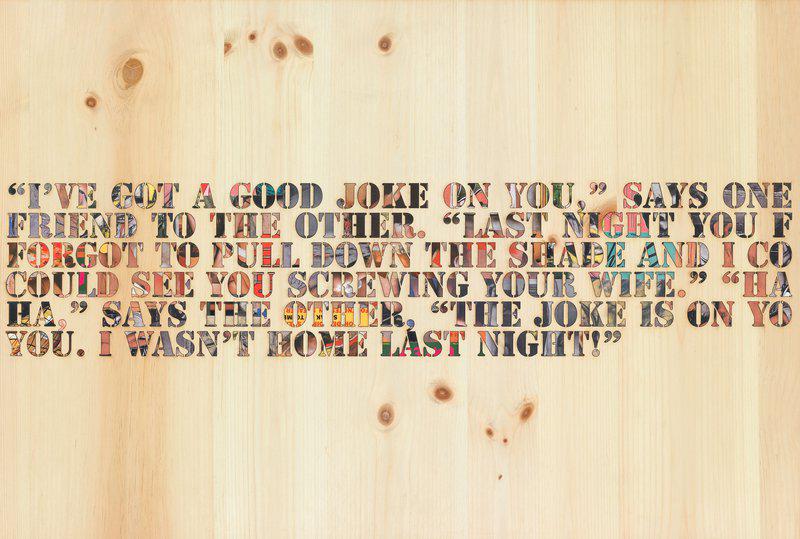

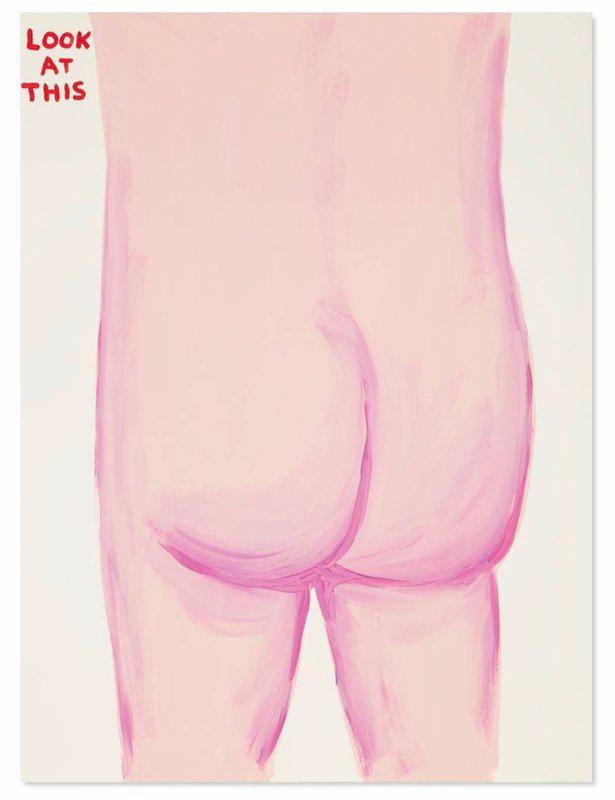

In the Biblical book of Genesis, Adam and Eve lived in blissful ignorance of their nudity. It’s only when they ate the fruit of the Tree of Knowledge that “the eyes of both of them were opened, and they knew that they were naked; and they sewed fig leaves together, and made themselves aprons” in order to hide their bodies from each other, and from God. Taboos are, to a degree, a socially useful tool, but such is human nature that whenever a line is drawn in the sand, some wag will overstep it for comic effect. Hence the sexual and scatological focus of much so-called playground humor, which of course thrives not only in the school yard, but also in the office, and even the retirement home.

This print by the Turner Prize-nominated British artist David Shrigley depicts a bare bottom, annotated with the words “LOOK AT THIS”. Why look? Because somebody in authority – a deity, a priest, a teacher, a parent – has placed peering at naked buttocks beyond the pale, and this is enough to make them both objects of fascination, and utterly hilarious. The great Mexican writer Rosario Castellanos once observed that “We have to laugh, because laughter, as we already know, is the first evidence of freedom”. Surely Shrigley – and all other eternal school kids, from eight to 80 – would agree.

Listening to 'canned laughter' on the soundtrack of a TV sitcom is a disquieting experience. The reason for this is a sundering of the connection between cause and effect. Whatever elicited these pre-recorded chuckles, we can be certain of one thing: it wasn’t the action on screen. This work by the acclaimed Jamaican-born, New York-based artist Nari Ward deals not in canned laughter, but canned smiles, although it, too, has its unheimlich aspects. To make the piece, he and his kids grinned into a pair of tins, labelled respectively “Made in Jamaica: Jamaican Smiles” and “Made in America: Black Smiles”, before the contents were sealed for posterity. A Ward family portrait, then, and one that speaks both to its members’ histories, and the human habit of classifying people according to their country of origin. And yet, we might wonder whether a smile – a thing of ephemeral joy and beauty, which belongs to a specific moment – can survive inside a dark metal prison. Is it really a potable commodity? What nourishment would it provide, once the can is opened up?

Ward pays homage, here, to an earlier project by the legendary Italian artist Piero Manzoni, who in 1961 created 90 cans labelled with the words: “Artist’s Shit Contents 30 gr net”. But while Manzoni offered up a witty exploration of why and how art is valued – the cans were originally priced according to their equivalent weight in gold, with the price fluctuating according to the market – Ward’s work is more concerned with how histories of oppression, specifically slavery in the Caribbean and US, have carried over into the present, in ‘preserved’ form. Much racist discourse still exists around Black smiles (see, for example, some choice writings by the current British Prime Minister). What might it mean, then, to seal these grins in a tin, and put them on sale?

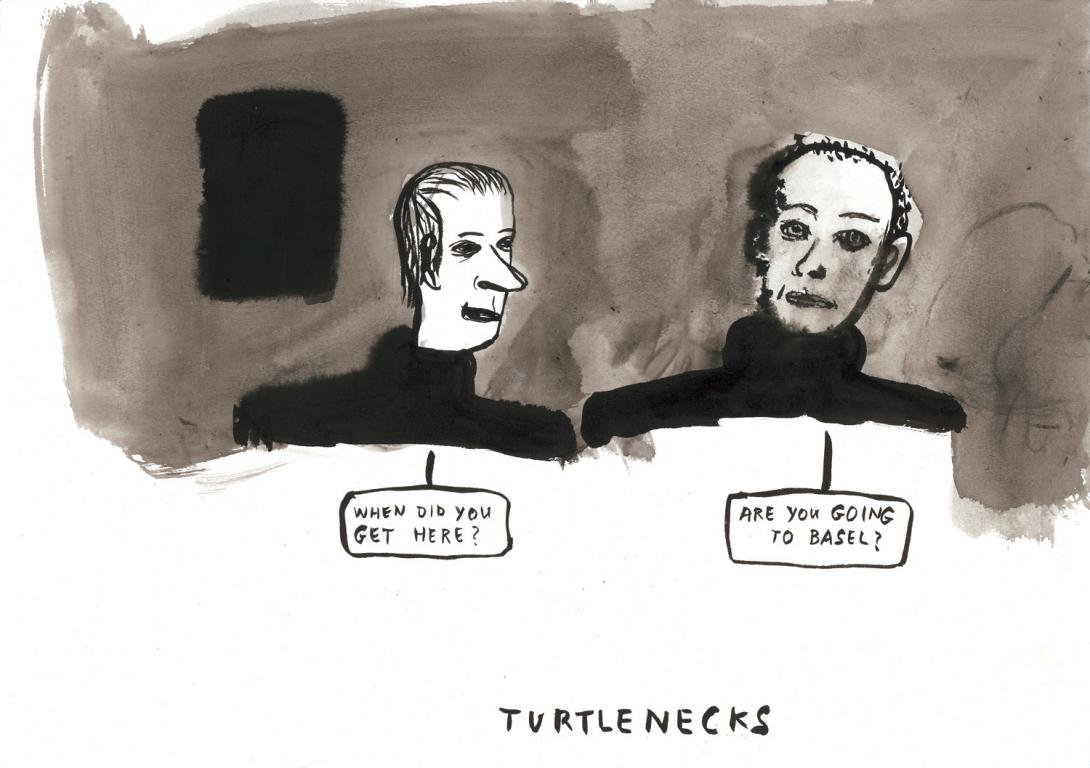

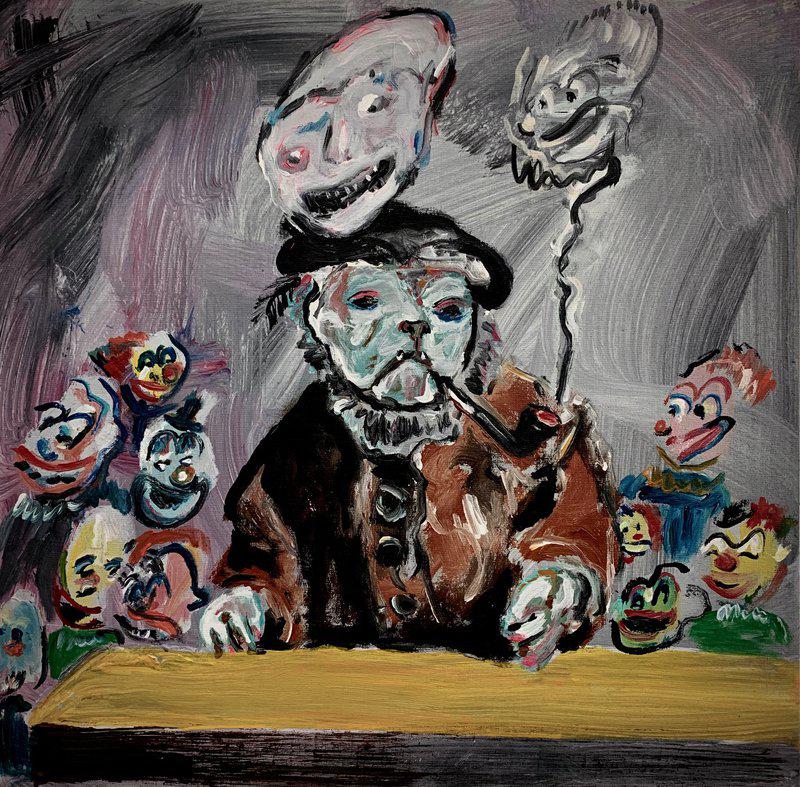

AMY SILLMAN - Turtlenecks (2007)

Insider jokes have long been grist to the artist’s mill. Think of George du Maurier’s illustration for Punch magazine Varnishing Day at the Royal Academy (1877), which shows the Academicians frantically attempting to finish their work ahead of the RA’s Summer Exhibition, or Gabriel von Max’s wonderful painting Monkeys as Critics (1889), which depicts a baboon daubing at a canvas, surrounded by a crowd of simian cultural commentators, who loudly chirrup their opinions as to its artistic merit. More recently, Bedwyr William’s satirical drawings have skewered a welter of art world types, from narcissistic, Balenciaga-clad curators to posh boy sculptors who affect a bloke-y, pseudo working class persona. Then there is the celebrated American artist Amy Sillman, whose large-scale abstract canvases are complemented by smaller, figurative works such as Turtlenecks, which target art folk’s foibles with laser-guided precision.

Anybody who has expended any shoe leather at a major international art event will recognize this scene. Fresh off their long-haul flights, two men in identical black turtleneck sweaters – that favourite garment of self-conscious intellectuals – meet by chance in an art fair booth, or biennale pavilion. There’s a painting on display, but both of them studiously ignore it – after all, art is really only an alibi that allows them to gossip, drink too much Aperol Spritz and (if they’re lucky) shimmy a few millimetres further up their industry’s greasy pole. Like a catechism, they repeat the same standard questions they ask fellow insiders at every event of this sort. Yes, of course these guys are “going to Basel”. Not to mention Venice, Frieze, the Whitney, the Armory, and every other art fair and biennale in the global art world’s calendar, from Hong Kong to Chicago, Busan to Istanbul.

NAN GOLDIN - Self-portrait Laughing, Paris (1999)

Laughter is a very difficult response to fake. In our daily lives, we might pass off a reasonable facsimile of attentiveness or sympathy, but to anybody bar the most boorish self-obsessive, a counterfeit chuckle will always be obvious. One of the reasons for this is that laughter is a spontaneous reaction. We can spare the feelings of a dreadful painter by telling them that their work is “interesting” (a useful private view hack, this), but the comedian whose routine fails to raise a chortle knows exactly where they stand.

The seminal American photographer Nan Goldin is known for the intimacy – and honesty – of her images, which often feature people on the margins of mainstream society, struggling with their own chaotic desires, and those of others. In this self-portrait, she captures herself in the throes of helpless laughter, her eyes closed and her mouth gaping open in a moment of wild, joyous release that verges on the sexual. And yet, if Goldin’s sides are really splitting, how is it that her unseen hands are steady enough to hold her camera? And who has the presence of mind to photograph themselves when they’re caught in a giggle fit? This image may appear to be utterly spontaneous, but what undergirds it is rigorous control.

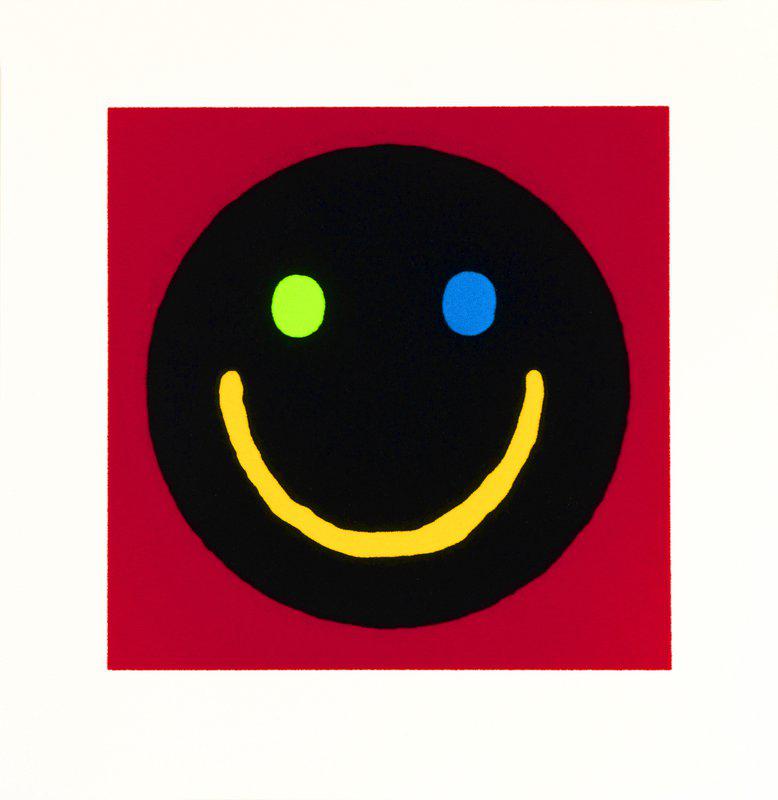

JAKE & DINOS CHAPMAN - The Banality of Evil (2020)

The phrase “the banality of evil” was coined by the political theorist Hannah Arendt in her book Eichmann in Jerusalem (1963), which focused on the 1961 trial of the Nazi Obersturmbannfüher Adolf Eichmann, for his involvement in the Holocaust. What she meant, here, was not that the defendant’s crimes were unexceptional – quite the opposite – but rather that they were carried out unthinkingly, and with no self-reproach. While Eichmann claimed that he was simply “doing his job”, Arendt’s text points to the fact that he and his fellow Nazis were always in possession of moral choice. As she wrote: “under conditions of terror most people will comply but some people will not […] Humanly speaking, no more is required, and no more can reasonably be asked, for this planet to remain a place fit for human habitation”.

Taking its title from Arendt’s phrase, this print by the Turner Prize-nominated British artists Jake & Dinos Chapman depicts a “smiley” symbol, tricked out in queasily clashing colors. Once associated with the hippy and acid house movements, the “smiley” lost its counter-cultural meaning when it was adopted as an emoji, used by everyone from Tik Toking tweens to Facebooking pensioners to communicate amusement or happy assent. Are the Chapmans mocking a conformist culture in which we’ve chosen to forego written language – and its infinite capacity to express complex thought – in favour of bland, pre-programmed ideograms? If so, they might have equally titled this piece The Evil of Banality.

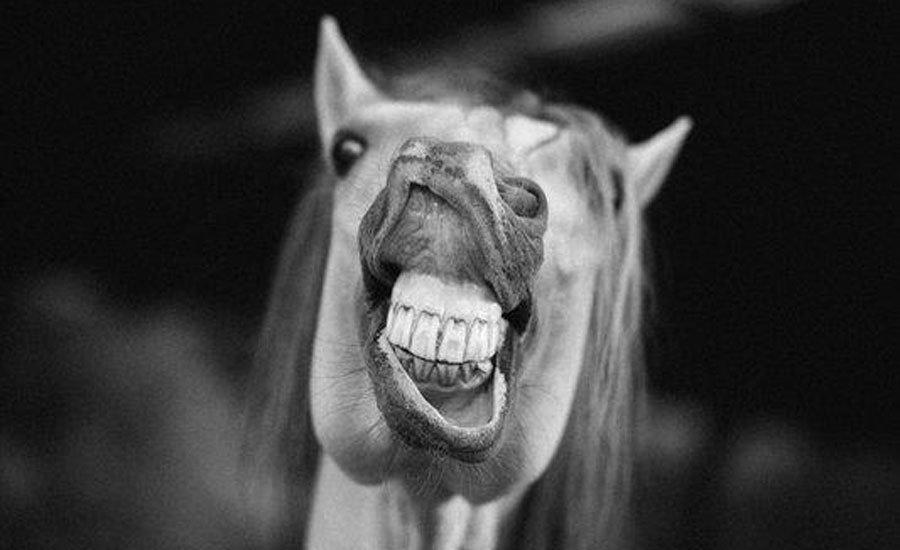

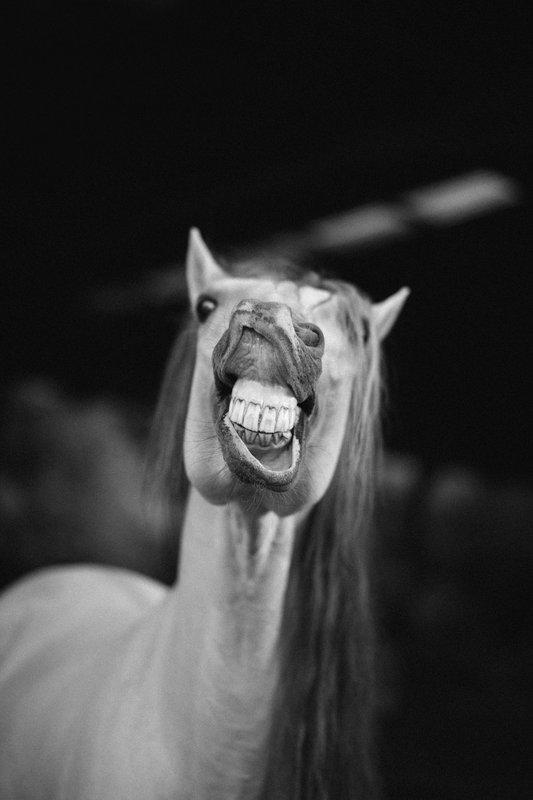

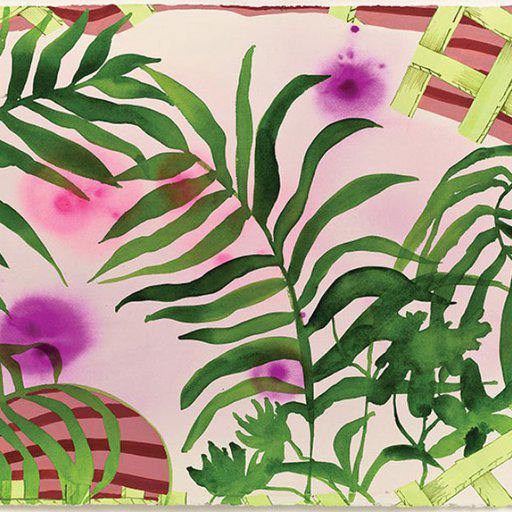

A horse walks into a bar. Glancing up from the beer taps, the bartender asks it: “Why the long face?”. This is an old and perhaps wearyingly overfamiliar joke, but there’s a good reason that it continues to be told. With incredible economy, the gag stacks knowingly absurdist misunderstanding upon knowingly absurdist misunderstanding: that the presence of an equine punter in a pub is unremarkable, that the creature’s permanently elongated muzzle is an index of its current emotional state, and finally that it is able to parse the publican’s words. Animal communication – from whale song to the octopus’s ability to change its pigmentation at will – is a many-splendored thing, but to relate and understand jokes of this sort depends upon the human capacity for language, which we alone have developed among all the lifeforms on Earth.

It follows that the horse in the noted Mexican artist Mariana García’s photograph Funny would be nonplussed by the linguistic stuff of set-ups, puns and punchlines. What, then, has caused its lips to twist into the appearance of a smile? Perhaps its unknowable equine brain has found something comic in the sight of García and her camera, or perhaps it isn’t smiling at all, but aggressively baring its teeth. While this shot may elicit a chuckle from human viewers (we usually imagine horses as handsome, soulful animals, not gurning goons), it also reminds us that humor is relative. There is no such thing as a universal joke.