Drawing inspiration as much from her Southwestern upbringing as the increasingly networked world around her, the artist

Robin Kang

is reinterpreting the age-old tradition of weaving with the added leverage of digital software. Kang—with the help of a very rare type of loom that combines hand weaving with computerized processing—makes woven tapestries depicting microchips, motherboards, and other elements of modern technology that remain quasi-mystical to the average Macbook user.

However, as the artist reveals in this interview with

Artspace

assistant curator

Jane Han

during a visit to Kang’s studio in Bushwick, the worlds of high tech,

textile art

, and ancient knowledge are not nearly as disparate as they may initially appear—read on to find out why.

What do you make?

Right now, the majority of my practice has been focused on weaving—specifically using the TC2 digital Jacquard loom. However, in the past I have also made video installations and sculptures. The technology and new media background plays into the woven work, as well as an investigation about the image within the picture plane of textiles. I like to approach weaving like a printmaker by exploring how I can create an image within the woven structure of the cloth.

Speaking of your video installations and new media background, you hold a BFA in Photography from Texas Tech University and received an MFA in Print Media at the Art Institute of Chicago. How and why did you start working with textiles?

Textiles have been present in my life naturally, initially by collecting vintage garments and handmade textiles from the Southwest, where I grew up, and later by expanding to include cloths from Africa, China, and Indonesia, among others. It’s kind of a personal passion—I think it was somewhere along the way in early graduate school where I realized how inspired I was by them, and was using image-making processes in photo or printmaking to create patterns that referenced textiles and specifically weavings. It was just a natural step for me to start learning about textile construction.

I took my first floor loom weaving class during graduate school in the Fiber Department at the School of Art Institute of Chicago . The beautiful thing about SAIC is that it is a very interdisciplinary school. There’s a lot of freedom for students, and it actually encourages them to take a lot of classes in other disciplines and media. I felt like there was a lot of overlap between printmaking and the fiber world. That’s when I really started to fall in love with the technical process of weaving. There’s a lot of preparation, many steps that build up in the same way that you’d have steps in the dark room or while you are constructing a screen print. There’s a similar process involved with weaving, and I think I gravitate towards those kinds of techniques.

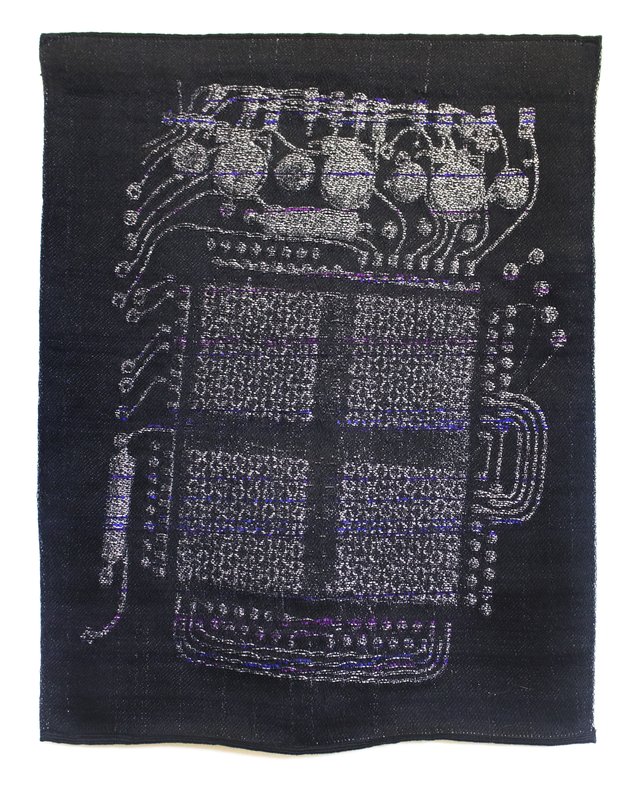

Quetzalcoatl SSD with Scratch

, 2016—available on Artspace

Quetzalcoatl SSD with Scratch

, 2016—available on Artspace

You said you grew up in the Southwest, which has a long tradition of weaving within the Pueblo and Navajo communities. Where in the Southwest did you grow up? And do you feel that living there has influenced your relationship to textile art?

Absolutely. I grew up in the small town of Kerrville, Texas, which is on former Comanche land, located outside of San Antonio. The landscape is largely ranchland embodying what you might imagine as a cowboy stereotype, including a strong history from the native people who were there. Childhood family vacations around the region included visits to New Mexico, Colorado, and south of the border to Mexico. Looking back, I’m sure my exposure to the gorgeous handmade crafts of these locations—whether textiles or ceramics—was a natural influence.

Additionally, I attended undergrad at Texas Tech University, which is located in west Texas in the city of Lubbock, an area that’s known for cotton fields. The cotton for the textile industry was literally being grown all around me while I was studying undergrad. Its logical to conclude those landscapes have had an effect on the current direction of my artwork.

Your Norwegian-designed digital loom, Thread Controller 2 (TC2) is the only digital loom in New York City. What is special about TC2 and how does it work?

To my knowledge, it’s the only one in the New York City—there may be others. To best describe how it works, I feel the need to first explain how the Jacquard loom differs from floor-loom style weaving. With the floor loom, warp threads are strung through heddles—they kind of look like eyes of a needle—and are tied in sections to foot pedals. You have to push those pedals in a certain order to make the threads lift and create your patterns.

With the Jacquard loom, the innovation involved replacing the foot pedal system by using punch cards, which had the capability of lifting the threads in more complex ways. It provided a faster way to make very complicated textiles. This was even before electricity—now most Jacquard looms are electric and automated. For instance, my loom runs on a vacuum pump.

Vibeke Vestby, the Norwegian woman who invented the TC2, looked to create a version of the contemporary Jacquard loom that embraced its digital capabilities but was still hand-operated, rather than automated. This allows artists and designers the freedom of speed and technologic innovation, combined with experimentation that comes about with weaving by hand. You have lot of room for material investigation because you can switch out colors and do things that would be not be very costly for—or could potentially damage—an industrial machine designed for speed and quantity. Vibeke wanted to blend the two and create a version of the Jacquard loom that was hand operated—that’s what this machine is.

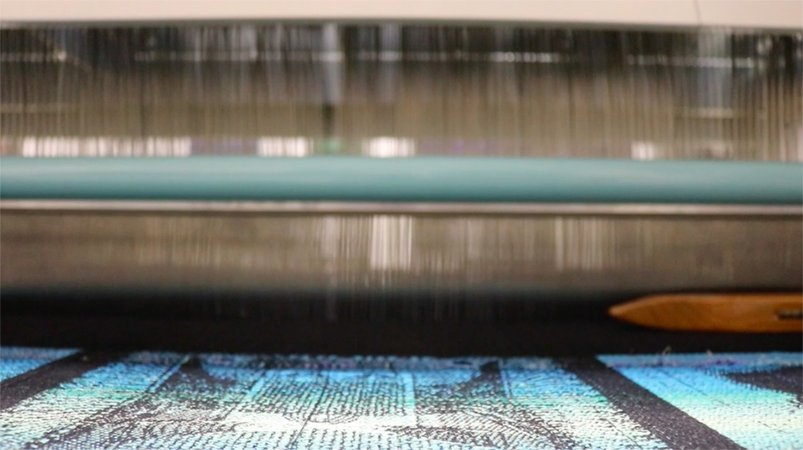

The Jacquard loom in action

The Jacquard loom in action

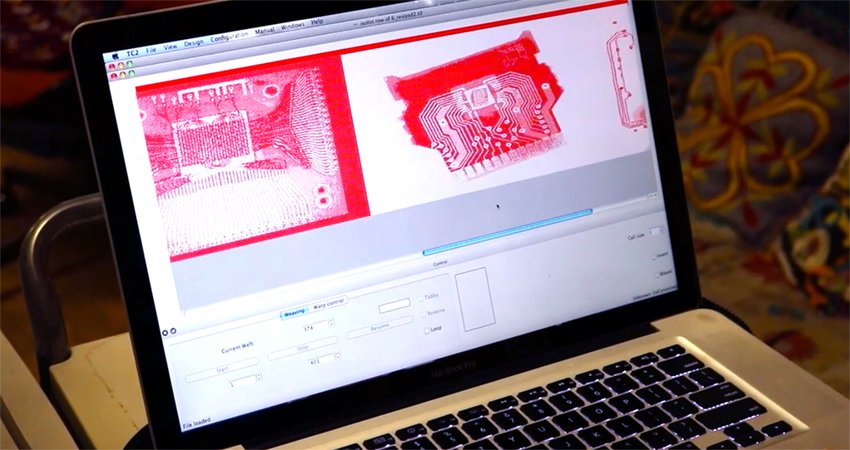

Files are designed on the computer, and then there’s a little bit of programming that happens where you have to translate the image into weave structures. Afterwards, you are ready to turn on the machine and begin weaving, which involves inserting the horizontal weft yarns by hand, while the digital loom lifts the warp threads per each line of pixels in your file. The TC2 is not necessarily designed for huge mass production—it’s meant for handmade projects, but it’s still fast, much faster than what could happen on the floor-loom.

I'm interested in the capability of pushing those moments where the pattern is broken through a color change or inserting unusual material such as plastics. It’s the idea of mixing an element of the hand-made glitch into our understanding of technology. In the textile customs of many indigenous cultures, there’s a practice of creating an intentional error within the piece—it's seen as an act of honoring the divine or indicating your imperfection. In Navajo culture it’s called the “spirit line”—a misplaced thread that looks like it’s breaking the symmetry but is actually intentionally situated there. I like to embrace this in my work as well—I find that it can take on an additional meaning in the context of the man versus machine conversation.

How do you decide what imagery to use for your textile pieces? What do you see as the relationship between computer chips and weaving, or modern technology and the loom?

Currently, there are two crossovers in the history of weaving and technology that have become inspirations to my imagery. The first is involves the history of the Jacquard loom. When the loom was invented, it was the first time punch cards were ever used in a mechanized process. The idea of punch cards as binary information carriers—where the cards are either punched or not, zero or one—was later used by another inventor named Charles Babbage, who appropriated this punch card concept for what is now considered the first computer. With this in mind, I've heard some people refer to the Jacquard loom as the grandmother to the computer. I think this is an especially beautiful reference because in Navajo culture, it was the grandmother spider who wove the universe in her womb and who taught humans how to weave.

The second crossover point involves the history of computer. During the first 20 years of computer history, the way the memory was stored involved woven copper wires and little magnetized beads. Those beads would be charged either positive or negative, again creating binary information but through magnetic memory. I find it fascinating that the early computer stored information through these little tiny weavings. Records indicate that it was mostly women who wove these because of the dexterity of their fingers, so there’s this amazing relationship between technology and the history of weaving.

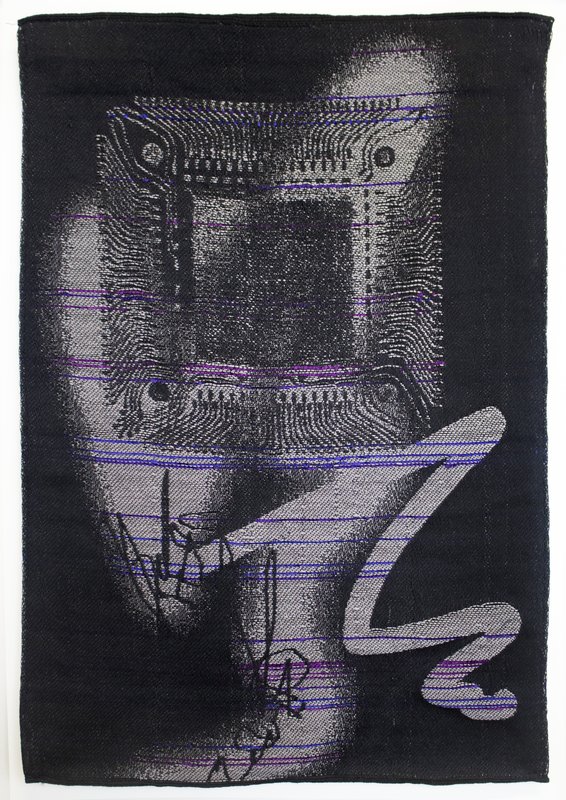

Memory Module Mask with Interference

, 2015––available on Artspace

Memory Module Mask with Interference

, 2015––available on Artspace

Much of my imagery evokes these magnetic memory cores—I just love the idea how textiles have a rich relationship with memory. Textiles have often been made to commemorate important milestones in life, such as a baby blanket, a wedding day dowry gift, or a protection shirt that’s created for a son who is going off to war. There’s memory, intention, and cultural identity wrapped up into this cloth that took someone an intensive amount of labor to create. It’s an interesting reference point for thinking about information and memory in the context of our digital culture. Some of them are more literal references to technology, and others reference symbols from a global textile history. Whether it’s ancient zoomorphic characters, iconic symbolism, motherboard hardware, or digital marks generated with photoshop spray brushes, it’s kind of all blended together, like a soup.

Kang's computer and imaging software

Kang's computer and imaging software

Through intention and references to history, many of the works present themselves in an almost totemic, quasi-spiritual way. Perhaps it’s a kind of investigation into ghosts in the machine and our collective consciousness, and a rapid technologically connected globalized world becoming reference points for when science, spirituality, and imagination meet. Much has been written and theorized concerning technology and mysticism, and I often enjoy listening to books and lectures while I weave. It all gets imbued into the work.

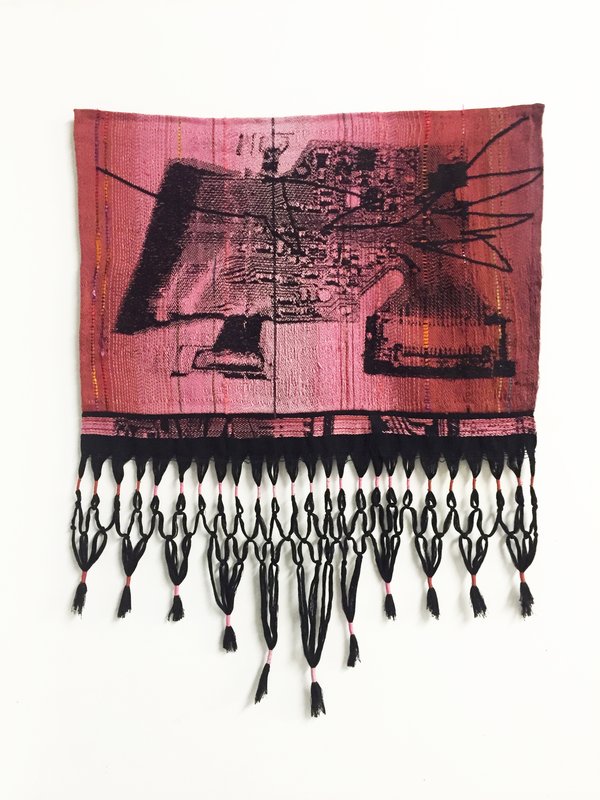

Encrypted

, 2015––available on Artspace

Encrypted

, 2015––available on Artspace

What kinds of limitations do you find using a loom that you wouldn’t face if you working a different medium?

I think the main difficulty is the considerable amount of prep and behind-the-scenes work that happens. Actually weaving the piece, the fun part, goes relatively fast. For instance, I had to thread all those threads in the loom first—there’s 3,520 of them, and they all had to go through their own heddles in a particular order! There’s also the process of winding the warp, which can take months. There’s lot of labor that goes into prepping the loom so that you can weave on it. It’s a challenge. I think when people hear about the digital loom there’s an misconception that it’s more similar to 3D printing, where I can push a button and the thing is created.

Despite the challenges, I enjoy working with process-based media and I find there are little moments along the way that keep things exciting and provide constant opportunities to push what I can do with the machine. There’s still a lot to experiment with.

Textiles have a long and revered history as religious, illustrative, and decorative handmade objects dating back to 10,000 BC. Though in the 18 th century, textiles were considered craft and often undermined as “women’s work.” Artists like Anni Albers , associated with the Bauhaus school of the 1920s, elevated textiles to the realm of fine art with modern, geometric abstractions. What role do you think textiles play in contemporary fine art now?

I think textiles have been more present within art history than people realize. There have been many waves of contemporary fiber and textile art since the Bauhaus. In the ‘60s and ‘70s these techniques were definitely very hot, and I think it’s interesting to note how that was also the moment when new media art was beginning as well. As with any movements that happen within the art world, there’s an adjustment period, and then it comes back around.

Now seems to be another moment where notions of craft, decoration, pattern, and high and low taste are being reconsidered within contemporary art. I’m interested in presenting a perspective from an artist who is living through this digital transformation and questioning what that means in the world of textile art. Our virtual lives are consuming a great deal of our being—perhaps at the same time there’s a need more than ever for the tangible and tactile, a desire for something that’s a slower, more physical process, and a place where textiles can fill a niche.

Kang and her work

Kang and her work

How do you see yourself and your work in relation to the tradition of textile art, a historically women-dominated field?

While there’s a Western connotation of textiles always being made by women, that’s not actually the case in many countries. For instance, in Turkey, men create much of the textiles.

Fiber by nature is a very inclusive media, existing in a somewhat "other" space, not being specifically painting or sculpture. That platform of inclusivity, as well as a carried notion of femininity, creates space for conversations about gender, politics, and identity. Regardless of what gender background you associate with, approaching the concept of femininity in contemporary art as a conscious tool for what you are talking about can be really interesting and powerful, especially in a time such as now when we’re seeing another wave of gender equality movements. Textiles have a central place in that conversation.

In contradiction to the feminine, I think there’s a largely masculine element to the technological aspects in my work—in the same way as textiles may be associated with women in western ideology, the connotation of the computer world is that it’s predominantly male. This blending of the two is interesting to me. However, the questions I’m most concerned with asking in my work have to do with process, history, memory, and the ghosts in the machine, though the associations with the materials will naturally be present.

What are some upcoming shows or projects you’re working on now?

It has been an amazing summer. Two fantastic shows just came down: "Common Threads" at Danese/Corey and the Queens Museum’s Biennial show, “Queens International.” Upcoming fall shows include “Escape Routes" at the John Michael Kohler Arts Center , two shows with Mathilde Hatzenbereger Gallery , one in Brussels and also Salon Zürcher in Paris, and my first solo show in New York at Outlet in Brooklyn , opening on October 7th, 2016.