With “ Richard Estes : Painting New York,” its survey of a pioneering photorealist, the Museum of Arts and Design has mounted the first painting show in its 60-year history. “Here at MAD, we believe that all forms of art and design are empowered by the knowledge base of craft,” the museum’s director Glenn Adamson writes in the foreword to the show’s catalog. “There is no reason to think that someone working in ceramics cannot be taken seriously as an artist. Nor does it make sense that a painter, especially a great painter, cannot be appreciated for his or her craftsmanship.”

It’s tempting to applaud his argument for further blurring the already fuzzy lines between art and craft, and to commend the museum for branching out into painting. Estes, a veteran painter who just had a retrospective organized by the Portland Museum of Art in Maine but is not as widely known as contemporaries like Chuck Close , is also an interesting choice. But taking a craft-centric approach to photorealism is a strange move—one that feels less contrarian than oblivious (and I don’t only mean oblivious to the trends in, say, MoMA ’s survey of contemporary painting.)

The issue should be obvious: Presenting Estes (or any photorealist) as a “consummate artisan,” in Adamson’s words, emphasizes the gee-whiz, how-did-he-do-that aspect of his technique, as if photorealism were merely a quest for verisimilitude. The movement has been misunderstood this way since Estes and his fellow photorealists, Close, Robert Cottingham , and Robert Bechtle among them, emerged in the 1960s.

Photorealism—also sometimes called hyperrealism, and distinguised by representations with camera-worthy fidelity to the seen world—has a quirky history, one that’s not really explored at MAD. Rooted in Pop and in the early-20 th -century American realism of Hopper and others, it flourished briefly in the late 1960s and early ‘70s and even claimed the international stage in the “Realism” section of Harald Szeemann ’s 1972 edition of dOCUMENTA. After that it faded away, as the decade’s Minimal and Conceptual art edged out painting of all kinds. Currently it has something of an academic reputation, and is overshadowed in the contemporary art world by the more trenchant, politically edged photo-painting associated with Gerhard Richter and Luc Tuymans .

Its revival here, under the auspices of craft, begs the question: is realism the only kind of painting that can claim to be “crafted”? Early in his career Estes himself voiced this point of view, in a 1977 interview where he said, “I think the thing about the Abstract Expressionists was that they were so involved with pure feeling and emotions that they didn’t bother with craftsmanship.” But today, with emerging painters like Sarah Crowner and Sergej Jensen exploring formalist abstraction through sewing, embroidery, and other craft mediums, that kind of thinking seems out-of-touch.

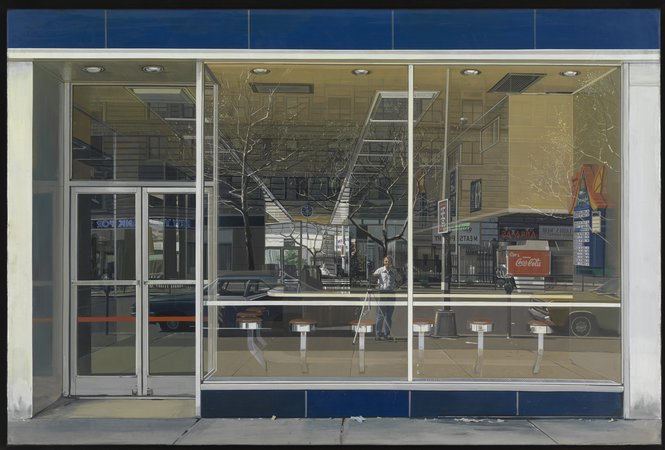

In other ways, the notion of photorealism as craft feels oddly passe. It ignores, for instance, the movement’s close relationship to Pop Art, which with its mechanistic polish was pretty much the antithesis of craft. The Pop influence is perhaps more obvious in the work of Bechtle, Close, and other painters who have used slide projections—Estes has not—but it’s certainly evident in his numerous renderings of restaurants, storefronts, and other commercial settings, which pay meticulous attention to advertising signage. In Double Self-Portrait (1976), for instance, the Coca-Cola logo on a soda fountain seems to press up on the foreground even as it’s tucked away behind a plate-glass diner window.

Richard Estes,

Double Self-Portrait

, 1976. Oil on canvas, 24 x 36 in. (60.8 x 91.5 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York, Mr. and Mrs. Stuart M. Speiser Fund, 1976.

Richard Estes,

Double Self-Portrait

, 1976. Oil on canvas, 24 x 36 in. (60.8 x 91.5 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York, Mr. and Mrs. Stuart M. Speiser Fund, 1976.

Celebrating the craft of Estes’s paintings also threatens to draw attention away from their content, which is important; he’s a painter of cityscapes who takes a genuine interest in architecture, parks, and public transportation. Comparing older works like Bridal Accessories (1975), with its view of mom-and-pop shops, to newer ones like Columbus Circle Looking North (2009), dominated by the sleek, curved façade of the Time Warner Center, gives you a kind of time-lapse view of the city’s gentrification.

Richard Estes,

Bridal Accessories

, 1975. Oil on canvas, 36 x 48 in. (91.44 x 121.92 cm). Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Graham Gund. Photo by Luc Demers.

Richard Estes,

Bridal Accessories

, 1975. Oil on canvas, 36 x 48 in. (91.44 x 121.92 cm). Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Graham Gund. Photo by Luc Demers.

Maybe that’s why MAD’s show also plays up the New York City angle, stressing tourist atttractions such as the Brooklyn Bridge and Staten Island Ferry and other points of interest closer to the museum such as the Empire and Plaza Hotels. It has even installalled Columbus Circle Looking North (2009) next to a window that offers a similar vantage point.

Installation photo of "Richard Estes: Painting New York City," 2015. Photo by Butcher Walsh © Museum of Arts and Design.

Installation photo of "Richard Estes: Painting New York City," 2015. Photo by Butcher Walsh © Museum of Arts and Design.

This relentlessly local approach sometimes has the effect, though, of making Estes’s paintings look like giant postcards, rather than sophisticated meditations on the ways in which photography can merge with sight and memory to enhance our experience of a place. His dizzying new work (2014-15), for instance, offers up a wide-angle photograph’s wealth of detail, turning a routine trip to the deli into a visual feast.

Richard Estes,

Corner Café

, 2014-2015. Oil on canvas, 38 x 60 in. (96.5 x 152.4 cm). Private collection, courtesy of Marlborough Gallery © Richard Estes, courtesy Marlborough Gallery, New York.

Richard Estes,

Corner Café

, 2014-2015. Oil on canvas, 38 x 60 in. (96.5 x 152.4 cm). Private collection, courtesy of Marlborough Gallery © Richard Estes, courtesy Marlborough Gallery, New York.

A look at Estes’s rarely-exhibited source photographs, many of them pieced together into panoramic photo-collages, confirms that his paintings are highly constructed objects. He uses photography selectively, often editing out details like text on an awning, passengers on the subway, or his own reflection in a store window. Pedestrian and car traffic is conspicuously absent from his painting Brooklyn Bridge (1993), a shutterbug's dream view of the city.

Richard Estes,

Brooklyn Bridge

, 1993. Oil on canvas, 39 x 78 in. (99.06 x 198.12 cm). Courtesy of Ann and Donovan Moore. © Richard Estes, courtesy Marlborough Gallery, New York.

Richard Estes,

Brooklyn Bridge

, 1993. Oil on canvas, 39 x 78 in. (99.06 x 198.12 cm). Courtesy of Ann and Donovan Moore. © Richard Estes, courtesy Marlborough Gallery, New York.

Perhaps this is what the museum means by craft: that Estes’s constant back-and-forth between working from photographs and in plein-air involves not just the craft of painting but the craft of visual editing. “His realism is not about simply copying or combining his photographs,” the show’s curator, Patterson Sims writes in the catalog. (Another large gallery in the show, meanwhile, is devoted to Estes’s prints, which he made at the urging of his dealer—the wall text even says so—and largely outsourced to master printmakers. There’s craftsmanship here, certainly, but it’s not the painter’s.)

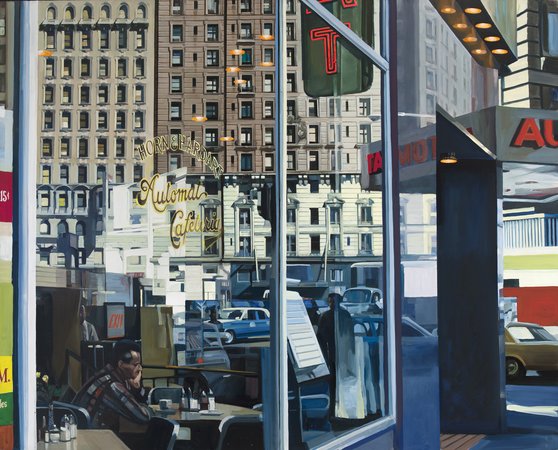

But in the show, Estes comes across as less of a photorealist than a realist, period, in the mold of Edward Hopper, George Bellows, and Charles Sheeler; he just happens to use photographs more than drawings. This makes you wonder what a craft-based reading of one of those painters would look like. Would it add to our knowledge of the artist, or would it feel myopic? Would any museum even attempt such an exhibition?

Richard Estes,

Horn and Hardart Automat

, 1967. Oil on Masonite, 48 x 60 in. Private collection. Photo by Luc Demers.

Richard Estes,

Horn and Hardart Automat

, 1967. Oil on Masonite, 48 x 60 in. Private collection. Photo by Luc Demers.

There’s much to be gained from the attention to process in “Richard Estes: Painting New York,” whether you call his methods of picture-making craft or just painting. In other words, if you’re not too bothered by the show’s terminology, you’ll learn something about Estes. But you may leave feeling that photorealism still hasn't gotten its due.