Though he’s lived in the artistic hub of Berlin for some 14 years, the Cape Town-born pseudo street artist Robin Rhode’s heart is still very much in South Africa. After all, it's the very real social and political issues plaguing his homeland that are often the target of his performative drawings—rendered in charcoal or paint on both gallery and public walls—that transform cars, bicycles, and other objects into metaphorical vehicles for wryly trenchant satire.

The approach itself is co-opted from an old South African high-school hazing ritual, in which newcomers are made to draw and interact with a figure as if it were real. Given his stated distaste for hierarchies of all kinds—born, one might assume, from his experiences growing up brown in the midst of apartheid—this merging of childish bullying with both graffiti culture and high art seems strangely apropos. Indeed, his career is now punctuated by his various forays into the world of pop culture, including (but not limited to) directing at 2014 music video for U2’s single “ Every Breaking Wave ”—featuring, naturally enough, his distinctive wall drawings.

Now, the 40-year-old artist is branching out into the realm of skateboard design, inspired by the good people at Skateistan (an NGO dedicated to supporting education and community-building among youth in troubled areas, including Kabul, Cambodia, and Johannesburg, by building skate parks that double as classrooms) and realized by the Skateroom , a company founded to sell artist-designed boards in support of Skateistan. (You can check out all of Rhode’s boards here .) In this interview with Artspace’s Dylan Kerr , Rhode discusses how this foray into extreme sports dovtails nicely with the rest of his work, and why he doesn’t love the distinction between high and low culture.

You’re one of the best-known South African artists working today— indeed, much of your work focuses explicitly on that context. At the same time, you currently live and work in Berlin. What’s your relationship to South Africa like today, as an expat?

You know, my relationship to South Africa is still really, really strong. I travel there at least three to four times a year. As an example, consider the production for the Skateroom. Of the five decks, I think four of them were produced in South Africa. All of those images were produced in South Africa, actually. A lot of my visual production still takes place in Johannesburg.

I’ve been living in Berlin for 14 years now. It has brought many, many challenges, especially with regard to accessing certain social spaces, coming as I do from a society with a certain political situation. Living Berlin is quite a different environment, politically and socially, than living in Johannesburg.

In terms of my working process, what I’ve done to find a balance between the two countries is to use Berlin as a kind of space for research—a place to analyze and to plan and to experiment. I use it to rehearse different drawing techniques and experimental shapes, different kinds of formal investigations, and to exercise different resources in terms of material. For me, Berlin is very much about a more analytical approach, while South Africa is more direct, outdoor, social engagement. There, my process is very much built around being more socially engaged and executing ideas that have been developed in Berlin.

Do you find that this distance helps you get your thoughts and materials in order, so that when you do go back to South Africa you’re mentally ready to go? It sounds almost like the difference between a studio and a gallery.

Exactly. I think for all of us, as people, having some distance from something familiar helps develop a new consciousness or a new understanding of that familiarity. We’re able to look at it with a different lens. This is what I do in Berlin—I develop various lenses through which I’m able to look back at my own country, my own history.

At the same time, this also lets me bring certain histories and ideas back to Berlin, absolutely. It’s not that I’m completely isolated and not working in Berlin in terms of executing works on walls or producing drawings—I believe that there should always be a dialog back and forth between these different spaces. I could have a particular experience in New York, and that experience could develop into a particular concept which is then realized in another part of the world. I think it’s really interesting and important to allow ideas to remain fluid and to remain relational. I think that is always important.

So, in terms of my working process, autonomy plays a key factor, because the viewer is never sure exactly where I’m making that work. I could be making a particular work on a wall somewhere in the Czech Republic, or it could be in Mexico—no one really knows. I’m very conscious about how a work remains autonomous with regards to geographic space. This means there’s either a shock happening conceptually, or through art historical references, are autonomous with regard to the exact location.

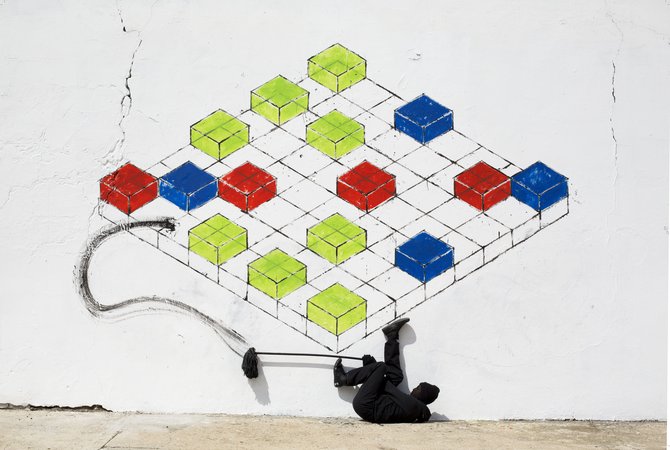

RYB

, 2016

RYB

, 2016

Do you find that your work is received differently depending on where it’s being shown?

I think, yes, there has been a difference in reception. It’s usually that the works produced in South Africa are more highly received, which then puts me under more pressure because I’m like, “Oh god, if I do something in Berlin it’s not going to be as good as something I did in South Africa.” Over the years, I have seen that there are very few works I’m producing in Europe that have the same resonance as works I produced in Johannesburg. It’s a really interesting dichotomy—it places me and my practice under more strain because I feel like, “OK, I have to make work in Johannesburg in order for it to be valid, in order for it to be supported.” This situation comes a lot of pressure because of the different reactions I’ve had to the work that I’ve produced in various contexts.

In earlier interviews, you’ve referred to yourself as a post-apartheid kid. What does this phrase signify beyond simply coming of age post-1994?

When I refer to the post-apartheid generation I mean my generation and the generations that have come after me, which I call the “born-frees.” My generation especially was the first to be exposed to a lot of Western culture, especially urban culture, massively . It had a huge impact on us.

What kinds of things are you referring to here?

I’m talking about skateboarding, hip-hop, basketball, fashion—American mainstream culture. We began to assimilate these kinds of cultural codes into our own culture. Those ideas were something the generations before me never even had exposure to.

We were able to do things like assimilate a New York Yankees baseball cap into a kind of local, South African street culture, by adding a local texture or fabric while still retaining the "NY" logo, or even adopt certain gangster codes from the United States into our own pop culture. That was really interesting, because we were a generation that was trying to find our own global presence—to do so, we were assimilating signs and codes from around the world, but mostly from the United States. Because of the black youth culture in South Africa, we gravitate a lot to the United States.

Now, there’s a whole generation of urban influence. One of the most dangerous street gangs in Capetown is actually called the Americans . How funny is that? They wear American flag bandannas around their necks. They even have their own drug house, which they call the “White House.” [Laughs.]

That’s incredible. It sounds like this cultural exchange wasn’t all positive.

To be honest, I don’t see the negativity, besides, obviously the drugs and gangsters and those kinds of situations. I think a lot of it was positive, because it opened up possibilities for people—it showed that there’s more than one way to live. There are so many ways to define oneself, and to define one’s own society. This was the first wave of globalization, and you wanted to ride that wave. You didn’t want to not be a part of it.

All the cultural overlaps between United States and South Africa in my generation really filtered down to the current generation of born-frees, who are now adopting more styles from Western Africa as well as from Europe and beyond. But for my generation, for the post-apartheid kids, we adopted the U.S.

Four Stories

, 2016

Four Stories

, 2016

Now that we’re more than 20 years out from the official end of apartheid, what do you think of as the biggest issues facing South Africa today?

The biggest issues starts from the president down: it’s corruption, and it’s crime. We have a lot of political corruption. At the moment we have a lot of issues with regard to tertiary education at the universities. We have what we refer to as “#feesmustfall.” There’s a huge issue regarding university fees, and a lot of protests saying university ought to be free for students. There’s a lot of instability at the university level. It’s a massive issue, but, again, it’s influenced by the presidency.

There’s so much corruption that it’s really influenced how people, especially young people, look at wealth and capitalism—the haves and the have-nots and the great discrepancy between the two. These conditions that are now triggering protests: people believe that there is no further way for us to develop or gain or evolve, so we have to protest now to have our voices heard and to be a vibrant and volatile society.

As much as it’s nice to have the distance, it also is good to be there because you really feel as if you are not part of the social revolution, it’s going to leave you. It’s quite an interesting democracy, so it’s good to be a part of this revolution for social and cultural change rather than being in Berlin, always comfortable and cool. It’s important to understand what the world is going through and to get a reality check.

These issues that you bring up are of vital importance in South Africa, but they’re also applicable to so many other places around the world, particularly the divide between the haves and the have-nots. Is this something that you’ve addressed in recent work?

I think it’s something I’ve always addressed. These questions have certainly shaped my practice since my student days in terms of embracing a public process of art-making. I’m talking about creating performances or producing wall pieces in the public realm, so that my audience were not the museum and gallery viewers but the unassuming audience, the public, on their way to work, commuting by bus or by public transport, or people that were occupying the streets who were homeless.

It’s still this way today. I produced work in South Africa a couple of months ago where I was working with a young crew. Some of them were homeless, most of them were on drugs, but they become part of my working process. My intention from the beginning was to allow for a new audience and a new participatory experience for people who do not visit the white cube—meaning museum and gallery spaces—and who don’t access the ideas of contemporary art or contemporary culture as such. Here, at least, they’re exposed to a contemporary process with regards to my practice.

From the start it was my intention to address those kinds of political issues, but in a very subtle way—a very playful, very funny, very humorous approach. I’m not a strikingly political artist as such, but I try to do it in a very subtle, unassuming, and humorous way.

How do you think humor becomes an effective tool for creating some of the changes that you’re talking about?

It's a very, very powerful element. If you grow up in a volatile society—under apartheid, for example—you start to develop very interesting, humorous takes on the world. You begin to use humor as a coping mechanism. Humor becomes a means of destabilizing a reality that is much harsher. Humor becomes subversion.

When I think about humor—and I think about it from learned experience—I have to think about William Shakespeare. I think about Twelfth Night , I think about Macbeth , I think about all these Shakespearian stories where there was a hierarchy, a king and a queen, because there’s always a joker. The role of the joker was always to play, to comment, and to critique, the dialog and soliloquies that were taking place. That’s such important device with regards to literature and I’m trying to use it exactly the same way, but from my lived experience. We joke about crime. We joke about racism. We start playing with those things, and when you do that you actually develop a new understanding of that particular condition. You’re actually critiquing those conditions through humor.

Sometimes, if I’m about to make a work that maybe I’m not fully confident in, I just say to myself, “You know what, I don’t know if this idea is really good. I’ll really try and do it, and while I’m doing it, I’ll try to make it as funny as I can.” At least take pleasure from the experience, you know what I mean? If people are laughing, I know it has the potential to be something interesting.

Lavender Hills

, 2016

Lavender Hills

, 2016

You mentioned just a minute ago that you started off drawing on walls, which of course has a long history as a radical, antiauthoritarian gesture. Now, however, it’s exactly those techniques that have won you widespread attention and the institutional and gallery acceptance that comes with it. Do you still see the impetus behind your work as coming from this rebellious or antiauthoritarian outlook?

I think that streak will always be there, but at the same time I always try to avoid this hierarchy between various spaces. For example, some of my early performance pieces were actually drawings in art exhibition spaces. I would do live performances within the white cube, with the original idea being bringing the outside walls into the planned, pure space of the white cube.

Besides producing those photographic or lens-based space work on exterior walls, I was bringing the outside world into the white cube from the very beginning. By drawing with charcoal or with clear paint on the gallery spaces, I was trying to activate the walls inside the white cube. As much as I embrace the outside element—that’s always my go-to space in terms of embracing the rebelliousness of the street—I also believe in bringing the street inside. I’ve done a lot of early pieces that are trying to destabilize the experience of the white cube as well.

At the same time, I’ve tried not to have a hierarchy in terms of being anti-white-cube. I’m saying that one has to critique both spaces, rather than some kind of rejection of one situation. I’m not like Banksy, against the gallery system or whatever. I’ve been part of it from the beginning.

Do you think that art has the power create real social change? If so, how do you think that process happens? Does it have that power?

I think it always has. I think that art has always produced social change. I mean, we sometimes even look at Renaissance paintings, to critique our current political situation in the world. I think, even today, art strongly reflects our current global situation, politically and socially.

Artists absorb society, and our art functions as a reflection on that society. I think great artists are those that use that reflection to create a new universe for the viewer. I think that is what I aspire to as an artist. I want to create this universe where people really feel that they are a part of something: a language, a place, that is actually tangible.

RGBG

, 2015

RGBG

, 2015

Speaking of creating social change: when I last spoke to the founders of Skateistan and the Skateroom , they were in the process of building and finalizing a new skate park and educational facility in Johannesburg.

We did it.

So it’s complete now? Great. Beside producing these new boards, what was your involvement with that effort?

I was in some early discussions with Oliver Percovich of Skateistan about the idea of the skate park in Johannesburg. I knew a property developer in Johannesburg, and things just kind of fell into place with regard to finding adequate space for the skate park.

Besides that, my involvement was in the opening. I shot and produced two skateboard videos, one focusing on Tony Hawk as well as capturing the skateboards of Paul McCarthy , the artist from Los Angeles. I also helped them get the sculpture out of customs for Skateistan. Paul McCarthy did a beautiful bronze sculpture and gave it to Skateistan.

I know he helped fund this whole effort.

Exactly, he helped finance the project. I will be contributing to the Skateistan program in the near future, definitely. I believe so much in their work, I’m getting citizenship. Skateistan citizenship! I’m not a German citizen, but I’m a Skateistan citizen, how about that?

Do you skateboard yourself?

I skateboard inside my studio, yes.

What are your thoughts on your work with Skateistan?

Love it. It’s probably one of the most exciting projects I’ve been involved with. I get to do a lot exhibitions, a lot of shows with museums or commercial galleries, and I’ve done a few videos—I did a music video for U2 a couple of years ago—I’ve done a piano concert for Lincoln Center, I’ve done projects that fit outside the contemporary art world. But the skateboard decks? [exhales] It’s just killer. I just love them.

I loved creating the decks because it was so clear—finding the verticality in the photograph. It was as if those images were meant to be those skateboard decks. Art has to transcend, you know what I mean? Here, the work transcends beautifully. It just goes gorgeously onto the decks. I’m so excited for all of it, and I’m so happy that people have the chance to access public space through my art—people are using my art to navigate architecture!

This is why I love the Skateroom and Skateistan. I’m doing a skateboard deck now for the Skateistan skate park sin Cambodia, in Kabul, as well as in Johannesburg. It just feels like, yeah, that’s the right thing. And that’s why I’m really so excited about it—I can’t wait for the deck to be launched now. It’s more exciting than me having an art exhibition, I can tell you that.

[related-works-module]

Robin Rhode x The Skateroom from Artspace on Vimeo .