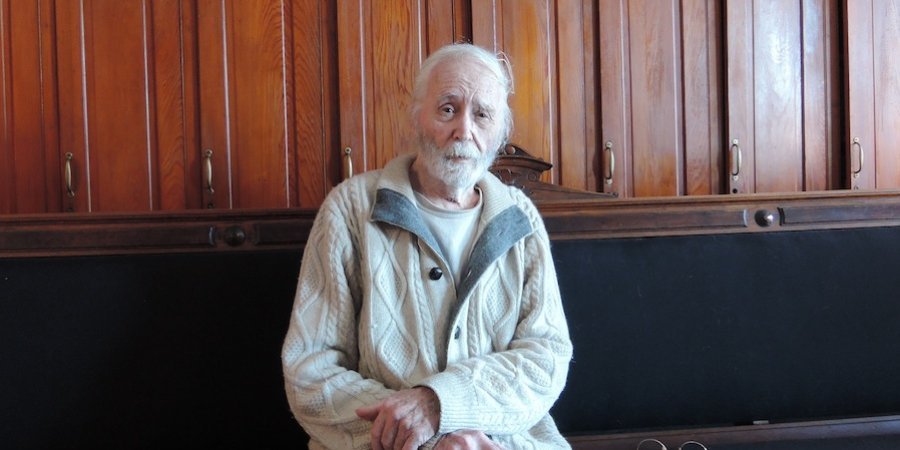

Internationally renown for his iconic LOVE artworks, Robert Indiana is responsible for one of contemporary art's most recognizable bodies of work—and, at the same time, one of the most overlooked. That is because the titanic success of LOVE, which grew out of an early 1961 painting titled 4-Star Love and evolved into a beloved series of prints and sculptures, cast the rest of his extensive career's worth of work in shadow. Now, the Whitney Museum of American Art is redressing this art-historical injustice with "Robert Indiana: Beyond LOVE," an exhibition showcasing a half century of the 84-year-old artist's work.

Curated by Barbara Haskell, the survey will also make up for another missed opportunity: Robert Indiana, who is closely associated with New York's Pop Art revolution, has not had a show in the art capital in three decades. This is partly owed to the artist's own absence from the city, since in 1979 he moved to the remote Maine fishing island of Vinalhaven, where he occupies a grand house on the main street that formerly was a lodge for the Oddfellows society. Overflowing with his art, the building also functions as an artwork itself—after the terrorist attacks of 9/11, Indiana boarded up the first-story windows and painted their surfaces with large American flags. He has rarely ventured from this refuge, where he has continued to make work, and to stay largely aloof from the wider art world.

To mark the opening of the Whitney's historic exhibition, which also features many of the artworks associated with LOVE—including the lesser-known word paintings EAT and DIE—Artspace editor-in-chief Andrew M. Goldstein traveled to Indiana's Vinalhaven home to speak to the artist about his influential career, and the way his landmark masterpiece has been both a blessing and a curse.

Your retrospective at the Whitney marks both a dramatic homecoming for you and an exciting time for the art community, which will finally be able to engage with the full sweep of your life’s work, not just your famous LOVE pieces. The anticipation for this show has been significant.

I’m curious about that. I don’t know how anything could be exciting in New York—there’s nothing but excitement. How can one notice a tiny little drop like mine?

To get an understanding of the arc of your career and your evolution as an artist, let's start at the beginning. How did you first become interested in art?

I started drawing as a child. I have my childhood drawings downstairs. You can see them. I started at the age of six; I never stopped.

Did anyone encourage you to draw?

My first-grade schoolteacher. She was very important to me because at the end of the first grade in Mooresville, Indiana— which of course was John Dillinger’s hometown, and I went to the same school that John Dillinger went to—my teacher kept a couple of my drawings, saying that she wanted them because she knew that one day I would be a famous artist. And that’s what happened.

How did your interest in art start to evolve?

My mother and father tried to discourage me from being an artist. They said that I would be living in an attic eating bean soup. I like attics, and I like bean soup, so I didn’t fail. I majored in art in high school—art, journalism, and Latin—and I did six plates in the manner of medieval manuscripts, in the Latin portion of the Bible. And that’s been on display in my high school in Indianapolis ever since. Lots of words.

After school you enlisted in the air force. What was that experience like for you?

I worked as a PIO editing newspapers, first at a military newspaper in Alaska. Then I ended up out on the Aleutian Islands, where I got so ill that I had to be sent back to the mainland, and then when my mother died I returned home.

You then came to New York in 1954, at a time when Abstract Expressionism was hitting its late peak and beginning to transition into Color Field painting, Pollock was gone, and de Kooning was leaving for the Springs. What was the art scene like at that time, and how did you locate yourself as an artist working in this city of Rothko, Kline, and other heroic artists?

Well, before I moved to Coenties Slip I lived further uptown, and my window on 4th Avenue—I had a loft—and I could watch de Kooning painting in the nude. There was no air conditioning; this was the ‘50s. De Kooning was the only one I actually personally knew. We used to eat in the same restaurant in the Village, and as I say, I would look out my back window and watch him painting. That was the extent of my involvement with Abstract Expressionism.

What did you make of the work that they were making at the time—their style of rawly emotional, grandly expressive painting?

I was not too fond of it. And it was too exclusive. They were a very tight club. They didn’t like interlopers. They did not like Pop artists—they were very much against Pop artists.

When did you start to see your work through the lens of Pop art?

At Coenties Slip.

So how did you find your way to living in that very fertile artistic enclave?

Because for three years I was clerking at the Utrecht Art Supply store on 57th Street, just a block down from the Art Students’ League, and I got to the point where I was allowed to arrange the windows. One day, a young man came in and asked for this particular postcard by Matisse, and that gentleman was Ellsworth Kelly. It was he who introduced me to the Slip.

The building that you found there famously had giant lettering up and down its façade, which art historians have pointed out is interesting considering the text that soon began to appear in your paintings.

Yes, I lived in an Indiana, as here I live in an Indiana in a different level. That was a slum—for $25 a month—and this is closer to a mansion. As for the lettering, I might not have done it, but it was done for me, you see. Needless to say, that might have played a small part in my development. Architecture has always fascinated me.

At the time there was a great deal of artistic ferment in the area. Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg were working nearby, as were Agnes Martin and James Rosenquist.

We were not cohesive. Johns and Rauschenberg were not in fact a part of Coenties Slip. They were a block away, and we had nothing to do with them—they were too successful.

Did the work they were doing have any influence on you?

Nothing on myself. The chief connection there was that Rauschenberg and Johns were very friendly with Cy Twombly. Cy Twombly had a miserably small studio, and in order to have room to paint his last show at the Stable Gallery, he asked if he could use my studio since I went away every day to work at the art supply store. Because of that, he would come in while I was working. Then one time Johns and Rauschenberg came to my loft and gave Twombly a critique, and it was a mind-blowing critique. One squiggle had to go this way, and another squiggle had to go that way. It was very illuminating, and very informing, I think. And, actually, I worked for them another time. Once when they fell behind in an assignment to decorate department store windows they needed extra help, and through Ellsworth Kelly I was recruited to help them do that.

When you say that it was at Coenties Slip that you became drawn to Pop Art, how did that occur?

I did not like the word. I was not fond of being called a Pop artist. I was Hard-Edge, I was not Pop. And I still think of myself as Hard-Edge. However, people still get confused and think that I am Pop.

That's interesting, considering that you are often cited as one of the earliest and most influential Pop artists.

I can’t help but say that writers go astray!

What other Hard-Edge painters did you see yourself as being in league with?

Only Ellsworth Kelly. He introduced me to Hard-Edge and was a great influence on my work, and is responsible for my being here. At the time, there were not so many Hard-Edge painters.

But your style also owes a debt to Charles Demuth and Marsden Hartley, who was working in a style that seemed to prefigure Hard-Edge.

I was influenced by Hopper, and I was influenced by several people from that particular genre. Do you know what influenced me? Life magazine. I saw art not in museums, not in galleries, but in Life magazine. The man who bought this building for me worked at Life magazine. One coincidence after another

When you were working on Coenties Slip, it seems you were also influenced by the imagery of waterfront.

Really just the signs—the signs on the sides of posts and trucks. I like words. I’ve liked words ever since I was very young, and also highway signs and numbers. The largest portion of my work deals with numbers, and the numbers come from the fact that as a child, I lived in 21 different houses before I was 19-years-old. My mother moved from house to house, and because we had nothing else to do on the weekends, we would travel the city, checking out those houses. So there became House Number 1 and House Number 2, et cetera, et cetera. That has greatly influenced the path of my work.

What is it about signs that interests you most?

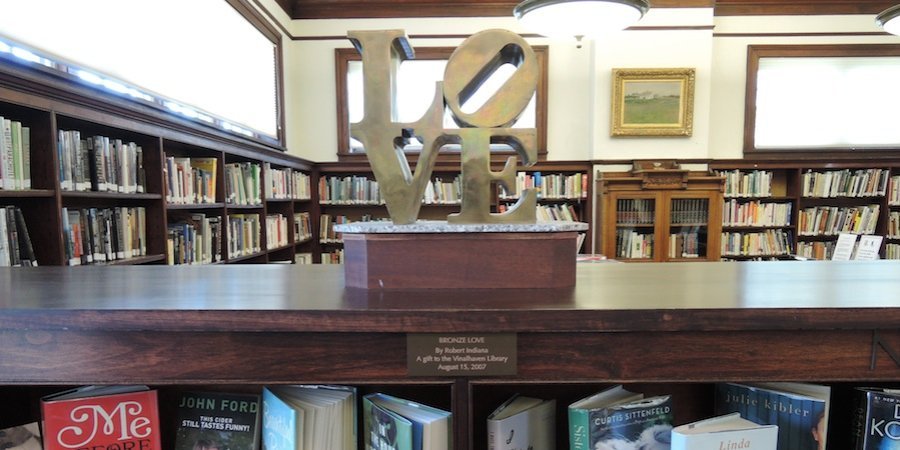

They have messages. I would prefer that all of my work has a message. Every painting that I do says something about something. The peace paintings, et cetera. This house I live in used to be an Odd Fellows lodge, and their motto was "Friendship, Love, and Truth." And that’s what I’m very much involved with: friendship, love, and truth.

Early on you began making your sign paintings using stencils that were highly specific. Can you talk about them?

Commercial brass waterfront stencils from the 19th century. I found them in my loft in Coenties Slip. They were lying there on the floor, I picked them and started using them, and I’ve been using them ever since.

Tell me about your process. Do you lay the stencil directly on the canvas?

Of course. I draw it, then I fill it in with color. I also do papier collé. I cut out letters, and I cut out forms, and often a work is composed and arrived at by papier collé. That’s particularly true of the work that I did for the Gertrude Stein opera. You’ll be able to see that in the exhibition.

The shape of the stencil also has informed the composition of your canvases. You’ve used circular and diamond-shape canvases that echo the circular and diamond shapes in the stencils you found in the attic.The tondos are an especially notable format, since one doesn't see that used in art so much anymore. It's more closely associated with artists like Tiepolo or Michelangelo.

It is rather an antique form, and I had the fantasy that I might be resurrecting something. Nothing got resurrected, but that’s all right.

In this same period you were on Coenties Slip, you also started working on totemic wooden sculptures.

Because I found pieces of wood outside the street, which I couldn’t resist. I dragged them upstairs, and I started working on them. That was called assemblage. Remember Louise Nevelson? An old friend.

You had a specifically Roman twist on the sculptures you were making.

Greek, Greek-Roman. With the Herms, definitely, because I studied Latin for four years, and I was very much involved in that world. So I was immersed in all that, and it was bound to come out in my work.

These sculptures are a fascinating combination of the graphic text painting that you were working on at the time and also this classical sculptural form from antiquity, which you recreated complete with its apotropaic, phallic protuberance. Why did you decide to combine them?

How could I resist? When I lived on Coenties Slip, the wood was outside my front door. When I moved to the Bowery, there was no wood outside the front door, so I primarily dealt with paintings. Then when I came to Vinalhaven, there wood outside my front door again, so I began making the sculptures again.

How did your career start to take off in New York?

One thing happened: I showed work in the basement of Martha Jackson’s gallery. She was a leading New York dealer. One day, after two unsuccessful shows in her son’s gallery downstairs in the basement, someone named Alfred Barr came in and purchased my paintings, and that was the beginning of my career.

Barr, the legendary Museum of Modern Art director and curator, then issued a press release stating the reasons that he bought your painting, the now-classic American Dream. It transformed you into an overnight sensation. You then went on to show at the Stable Gallery, one of the most prestigious spaces of the day.

Several times, and the first time with Andy Warhol and Marisol. We both had our first one-man shows at the Stable Gallery in 1961.

What was that moment like?

It was all very exciting. Things were happening, and that went on for several years. Then, finally, I closed the door and came to Vinalhaven for peace.

You once called yourself "a people’s painter" as well as a painter’s painter.

In other words, that’s why I did prints. I did prints so that everyone could own an Indiana, not just the richest people. That was my intention.

One oft-overlooked aspect of your work is your mastery of the painting technique itself? What is your approach to the canvas?

There’s something called paint, there’s something called canvas, and there’s something called a brush. What else can happen? I don’t use cigarette butts. But it was nothing that I learned in school. That was the artist’s tradition at the time.

After Barr helped launch your career, you came to much wider renown in 1965 when MoMA officials saw your first LOVE paintings and commissioned you to create a Christmas card with the same imagery. What happened next?

It was the most profitable Christmas card the museum ever published.

The graphic layout of LOVE is notable for its jaunty "O" and the way that the letters stack together. It has a kind of musicality and rhythm. What inspired its composition, with the slanted "O"?

It’s an old typographic design, which goes way, way back. But with LOVE it seems to have struck a chord with all kinds of people.

This was in the mid-'60s, when opposition to the Vietnam war was building and the seeds of the hippie counterculture were taking root. The idea of love had taken on a political dimension, as an opposition to war and the consumerist direction of society. Was this on your mind at the time?

Not with LOVE necessarily. I did Peace paintings that involved the peace symbol. I did one of those for Bertrand Russell in England [for the philosopher's campaign against nuclear weapons] that had nothing to do with LOVE.

LOVE is seen frequently as a work of Pop art, but while Pop art tends to convey an arch sensibility, LOVE is sincere and seems to convey a belief or stance.

I have to agree, but you’re forgetting one thing: my LOVE is Hard-Edge. It doesn’t have soft edges.

What does love mean to you?

It has been a central focus of my life, starting very early with my mother. Many of my paintings, in fact most of my paintings, are autobiographical. My friends, my lovers, all kinds of people—dealers, healers, everyone.

Did the piece have anything to do with the idea of Christian love?

It did. As a child, I was introduced to Christian Science, the religion founded in Boston by Mary Baker Eddy. Love was a very dominant factor in her religion. Over her altarpiece in Boston is the word "love" is engraved in marble, and I was affected by that.

Is this a continuing religious presence in your life?

Not really, it’s all kind of history. But I’m watching that pope [Francis] right now. He’s a very suspicious character.

Much has been made of LOVE's success as a piece of its era's visual culture. It has achieved a universal recognizability that is hugely rare in art history—another example is the Mona Lisa, for instance. What do you make of its achievement?

Don’t forget Picasso’s Peace Dove. Let’s think about Picasso’s Peace Dove. Time does do its damage. People are beginning to forget about Picasso, when, of course, for me, a young artist, he was the dominating factor because of Life magazine.

As you mention, LOVE became copied and disseminated all over the world, showing up on t-shirts, coffee mugs, and all manner of merchandise. In the process, it has almost become a logo, or symbol, for contemporary art. What has been like to witness this incredible phenomenon take flight from your work?

Discouraging. I’m not pleased. I’m not fond of that aspect of my work, and I have nothing to do with that.

What was the effect on the art world? How did your peers respond?

By not speaking to me at all. It became, "Robert Indiana, LOVE, ugh." That’s all. "Robert Indiana, LOVE, ugh." Too much. Jealousy, envy. Artists are human. They exhibit human traits.

You also built LOVE into a spectacular sculpture that is one of the most beloved works of the public art in New York. How did it evolve into a giant sculpture?

I started the sculpture editions in 1966, and the first large LOVE sculpture went to Boston, and then the one that was in Central Park in New York happened. It just went on from there. I later did AHAVA, the Hebrew word for "love," and that stood in Central Park in the same spot that the LOVE sculpture did. Now it’s in Jerusalem.

Why Hebrew?

The main reason for AHAVA goes far back into my past when I was a student at the University of Edinburgh in Scotland. I became friends with a young lady whose father was the Earl of Balfour. Her grandfather happened to be the man who established the state of Israel with the Balfour Declaration. I used to sleep in Mr. Balfour’s bed in Scotland. That sort of thing affects me. But because I’m fascinated with words and language I’ve also done AMOR.

After LOVE, you continued into other series that were even more forceful. One of these was your Confederacy series. These paintings took a very clear political stance, protesting the brutal treatment of blacks in the South.

They were very firm and very clear, and those paintings have suffered various fates. They haven’t always been everyone’s favorite Indiana work. In fact, there are people in the South who are not fans of those paintings at all—it keeps me from being in certain museums in the South. You don’t do racially charged paintings if you want to have success in the South. We are America, right? We love the South. A marvelous part of our country, right?

What exactly was it that inspired you to make those paintings?

All that racial turmoil that took place on the bridges and the harassment of the negroes. Dogs and firehouses and not letting them go to school…. It was a charged time to be alive. And I’d like to think my work might mean something and have some kind of influence.

From there, you transitioned into your Autoportraits, which is a series that you did over the course of the ‘70s. Can you talk about those works, which told your life's story through a series of numbers and words?

Like most of my work, it's autobiographical. It deals with my own life, my own history, my own thoughts. There are highway numbers, place names, names of rivers that I lived close to, everything involved with my personal life.

One of your most recent series, the Marsden Hartley Elegies, is a deeply personal tribute to the great American painter. How did that series arise?

Hartley never meant much to me as a student and as a young artist—only after I came here and found that he had actually lived on Vinalhaven. Marsden Hartley lived here in 1938, the year that my grandmother was murdered in South Bend, Indiana. He came here and found a house, a lovely cottage, facing the water. Running water and electricity, six dollars a month. He thought he had found heaven. He spent one summer here and never came back. The kids threw rocks at him. It’s an island that greatly appreciates talent. It was a tragedy. My paintings were in homage to someone who suffered more than almost any other artist I know of. He had a terrible life filled with tragedy, and that does interest me. If you watch American television, you will see how fascinating people are with tragedy. One tragedy after another. It never ends. In fact, it gets rather monotonous.

Then, for a show at Paul Kasmin Gallery in 2004, you showed a group of Peace paintings that you had made in response to 9/11. You experienced that tragedy in an intensely personal way.

I was in New York on my way to attend the opening of my Marilyn Monroe show on the Cote d’Azur, and I was staying in a huge apartment complex downtown. That morning, I went to the bank to draw money so I could go and buy Marilyn Monroe T-shirts—I had done them a long time ago—on the 110th floor of the World Trade Center. I thought it might be great fun to take a dozen Marilyn Monroe Robert Indiana T-shirts for people at my opening. At the bank, I looked at the TV, and the first plane had crashed into the World Trade Center. And I rushed back home, took photographs of the burning towers. I watched the buildings fall in front of my face. What greater tragedy has ever happened to New York City?

As an artist, what do you feel is your role in society?

I’m an artist. I love making art. Period. Nothing more. I have no role in society. I’m a recluse. I’ve been up here for 40 years, totally out of touch with New York.

What are you expecting, what are you hoping for, when you turn to New York with this retrospective at the Whitney?

My feelings are that it’s slightly overdue. I’m here for 40 years and I don’t go back to New York. Once in a while, I have a show and I go for the opening. But now I’m having my first museum show in New York, and I’ve been around for 50 years. That’s how I feel.

The title of the show is "Beyond LOVE," and the curatorial intention is to place the focus on your career as a whole, minimizing the prominence of your signature series. For you, however, no matter how fraught the piece's history has been, LOVE still plays a central role in your life. In your home you have an entire career’s worth of art, but versions of LOVE take all the most prominent places.

I happen to like my work. I’m surrounded by LOVE.