Piotr Uklański emerged around the turn of the millennium with a flashing disco floor at Passerby , the West Village bar founded by his then-dealer Gavin Brown , and a photo spread of his partner’s derriere that ran in Artforum . The Warsaw-born New Yorker has since aimed his gentle provocations at bigger, less insidery audiences, moving from Brown to Gagosian and embracing friendly, amateur-friendly processes like tie-dye and macramé. This week, Uklański opened two shows at the Metropolitan Museum of Art : Fatal Attraction: Piotr Uklanski Photographs , the first survey of his photography anywhere, and Fatal Attraction: Piotr Uklanski Selects from the Met Collection , the latest exhibition in the Met’s series of artist-curated collection shows.

It's an interesting moment for both Uklański and the Met. As the museum moves aggressively into contemporary art, ahead of its takeover of the Whitney's Marcel Breuer -designed building next fall, it's giving a very contemporary artist a chance to show off his historical interests. Uklański is, in many ways, a less obvious candidate for an "artist's choice" exhibition at the Met than earlier picks James Nares and Kara Walker , who organized shows in 2013 and 2006, respectively.

Uklański's two exhibitions are crisply differentiated in their themes; one takes a focused look at a narrow slice of his practice, and the other is almost ludicrously broad with its themes of sex and death and its ancient-to-contemporary purview. Both shows, however, reflect the artist’s distinctive sense of humor, which the Met photo curator Douglas Eklund has defined as “cheerful pessimism.” The day after the opening, Uklanski spoke to Artspace ’s Karen Rosenberg about sifting through the buried treasures of the Met’s storage, his Oedipal relationship to the “Pictures Generation” photographers, and finding a new favorite painting.

When you moved to New York, in 1990, you studied photography at Cooper Union. But before that, at school in Poland, you had studied painting. Since then you’ve continued to work in both of these mediums and branched out into several others. Why have a show at the Met of just your photographs?

As an artist I think in images, and as a result I enjoy the idea of putting the camera, photography, at the core of my practice. I have been photographing, always, but somehow it’s not seen as my main focus. Actually, it’s interesting because it’s been coming to me the last two years, when I started to work with photography again. Unfortunately, in the context of this Met show, a historical situation, you don’t really see the so-called new photographs.

The curator of your photo show, Douglas Eklund, also organized the 2009 "Pictures Generation" exhibition in the same gallery your survey now occupies. In discussing this show, he has referred to you as a post-“Pictures Generation” artist—someone who’s answering the question, “Where does one go after appropriation?” Does that ring true to you?

Yeah. I came of age looking at these guys, and then I tried to kill them.

Were you inspired by anyone in particular, from that group of artists?

[Sherrie] Levine , [Richard] Prince . I had a rather hardcore photographic background at that point. These are the people who showed me how wrong I was.

I saw that you included a large Laurie Simmons photograph, Walking Gun ( 1991), rather prominently in your curated show… was that a nod to the “Pictures” theme?

Absolutely—and to women. Because this selection, as much as it is mine, is sourced out of what they have. It’s not the show of what I like, period. It’s the show of what I like and they have. I wanted to make that statement.

Laurie Simmons's Walking Gun (1991)

You mean, you wanted to make a point that there aren’t enough female artists in the collection?

Exactly. Well—what really struck me is how few of the Eastern European photographers there were. I only found one really good photograph by a Polish artist there, Stanislaw Ignacy Witkiewicz, who’s not even known as a photographer. This was striking. At the same time, you look at Helmut Newton, who’s not Polish, not a woman, and they don’t have that either.

It isn’t really a show about what they don’t have. But you pointed to Simmons’s photograph. I don’t set out to make statements like this through the presentation, but this was just right there and I thought it was important that it’s there. I wished the show could have less American, male photographers, but it’s what I was able to source.

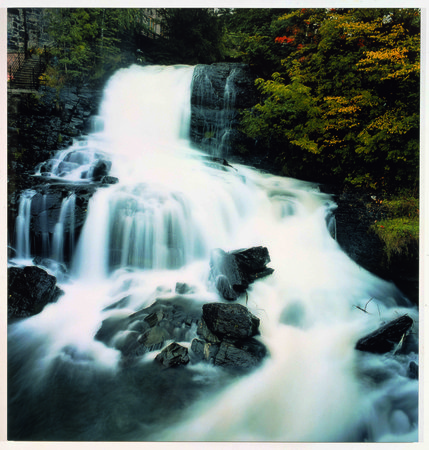

Many of the works in the show of your photography are from your early series, “The Joy of Photography,” which is based on a book of the same title—a 1979 Kodak manual for amateur photographers. What were you trying to do with this book?

I would prefer to put it in more abstract terms, because it wasn’t just Kodak. It was more about this idea of an enhancement of reality. For me, it’s somewhat poignant. There are all these photographs of faraway places, beautiful landscapes, the Caribbean… it was really about projecting yourself out onto something that was not attainable.

Piotr Uklański's Untitled (Waterfall) (2001)

In the show, your photographs are accompanied by a big sculpture: your twisted-fiber piece Untitled (Story of the Eye) from 2013. What’s it doing there, and how does it relate to your photography?

The department of photography at the Met mostly shows people who spend their careers doing photography. I do other things as well, and they’re equally important. This particular work I thought might be an interesting addition because it’s an eyeball, and photography in this most clichéd way is seen as an eye onto the world, or the soul.

Piotr Uklański's Untitled (Story of the Eye) (2013)

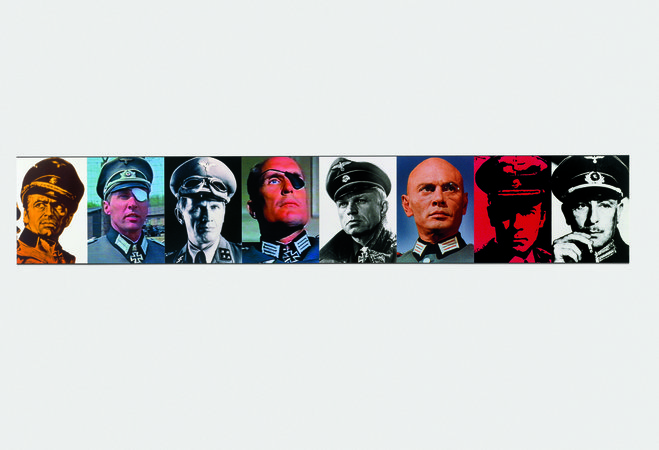

Among the photographs in the show, the most prominent piece is undoubtedly Untitled (The Nazis) , your compendium of appropriated television and movie photographs of actors in Third Reich uniform. It’s been installed here in an abbreviated way, with just 117 of the 164 panels, and in a different configuration, a kind of vertical grid. How do you think this changes it?

I did conceive of this work as a linear, horizontal piece, but at the time it was really conceived as a piece that is not supposed to coexist with anything else. What I like in this presentation is that it becomes one work of the many, rather than the most important work.

Over the years, the response to this work has varied widely; it's drawn both violent reactions and critical praise. What do you make of these different responses?

I don’t really understand why anyone would see this work as controversial. I don’t understand why people see frontal nudity as controversial either. I suspect that maybe my moral compass is a little off. At the same time, I think the work is what it is—it’s not abusing anybody, it’s just things that are picked out from the world out there. Maybe the difference in responses shows that it’s not the work that carries this negativity—it’s something people bring to it.

Piotr Uklański's The Nazis (1998)

When choosing works for your “artist selects” show, how much leeway did you have? Did you have the run of the house?

I wouldn’t say I was restricted. There are always issues of availability, just as in the show of my photographs. You have to choose what’s there. So within this paradigm, I had carte blanche.

Many of these works, the museum says, came out of storage. Were you making a conscious effort to dig deep, to highlight lesser-known objects?

When I tried to convey the theme, which I like to think of as “Beyond the Pleasure Principle,” I was looking for situations that are not obvious and subjects that are not obvious subjects of photographs. This museum, any museum that large, is all about death—things we’ve done, what humanity has produced. When you make an exhibition that nods to that, it’s very hard to come up with a different kind of presentation. That was sort of an M.O. of mine, looking for other positions within all these positions.

You seem particularly interested in sculptural fragments, like the piece of a queen's face from an Egyptian statue.

I felt that that’s how our memory works. If you look at The Nazis , it’s about retelling the story of something we don’t know. With museums that collect artifacts from the past, it’s a similar thing—we don’t really know. I wanted to echo this fragmentation.

Fragment of a Queen's Face , Egyptian, New Kingdom, Amarna Period (ca. 1353-1336 B.C.)

Tell me about the bit of graffitti you have handwritten, in Polish, on a wall of the gallery: “Life is a terminal disease transmitted via sexual intercourse.”

Often, these thematic shows have quotes. I wanted to echo that. I like that quote a lot. I didn’t see it on the street but it’s in the Polish cultural discourse—it’s very famous—and it does come off the street. Everybody knows it. It’s a bit of a cliché, but I found it very fitting.

The focal point of your "artist's choice" show is a salon-style wall of mainly photos, with a few small paintings and other objects mixed in. Why did you install this way? I’ve always wanted to do that. If I could, I would hang my own work like that, too. With museum collections, there’s a lot of hierarchy— you need to validate, you need to choose. A wall like this is a bit contrary to that. Times mix, positions mix. Often those artists would fight with each other if they were sitting at the same table.

Installation view of Fatal Attraction: Piotr Uklanski Selects from the Met Collection. Courtesy The Metropolitan Museum of Art / Don Pollard.

Installation view of Fatal Attraction: Piotr Uklanski Selects from the Met Collection. Courtesy The Metropolitan Museum of Art / Don Pollard.

This part of the show has a strong sexual undercurrent, enough so that the museum has placed a parental warning sign at the entrance to the gallery. There’s Larry Clark ’s photograph of teenagers in flagrante delicto, or that blue-period Picasso of a young man with a nude woman’s head in his lap, to mention just a few examples. Were you trying to shake up the Met’s genteel image, as well as its hierarchies?

I object to this question! There’s one erect penis on the whole wall. Picasso’s painting doesn’t show genitals—they could be picking each other’s pimples. Is Nadar's hermaphrodite photograph from the 1860s pornographic, or scientific?

I did look at the Japanese woodcuts, where every image of intercourse has explicit frontal nudity—vis-à-vis this, the images in the Howard Gilman Gallery are really tame. I think it’s metaphorical—it’s alluding, rather than showing. And if you have Eros as a subtitle… if I didn’t show it, it would be like, “What is your problem, man?”

Do you have a favorite work from the selections you made?

It’s got to be the painting of Jesus Christ by Stephen Hawley. I think it’s a fantastic painting. The rendering of the figure is just insane—he looks like a male model. It’s a great execution and everything else is wrong, and I think that makes it a great artwork. It’s a favorite not because it’s the best, but because it was truly the most surprising—to see that kind of work, and that kind of work at the Met.

What has been your relationship to the Met, over the more than two decades you’ve lived in New York? Do you go a lot? Do you have a visiting ritual, or a favorite part of the museum?

I don’t really go out. I don’t have a relationship. It’s a weird experience, when you spend too much time there and you realize that all of it is a human production, and that they were so much better. It makes it harder to get up the next morning and go do your thing. The quality of human effort is really intimidating.