Could it be? Are we already post-Internet?

It's a bemusing term you may have heard floating around the art world recently, and now a new exhibition called "Art Post-Internet" at Beijing's Ullens Center for Contemporary Art—organized by critic/curator Karen Archey with writer/gallerist Robin Peckham—has set out to encapsulate the budding movement, which may be the most significant of its kind to emerge in a while.The key to understanding what "post-Internet" means is that, despite how it sounds, it doesn't suggest that the seismic technological developments associated with the Net are finished and behind us. Far from it.

Instead, in the same way that postmodern artists absorbed and adapted the strategies of modernism—fracturing the picture plane, abstraction, etc.—for a new aesthetic era, post-Internet artists have moved beyond making work dependent on the novelty of the Web to using its tools to tackle other subjects. And while earlier Net artists often made works that existed exclusively online, the post-Internet generation (many of whom have been plugged into the Web since they could walk) frequently uses digital strategies to create objects that exist in the real world.

There are already a handful of artists and galleries that are closely linked to post-Internet art, and curators are aiming to sum up the way these artists reflects our new relationship to images and objects inspired by the infinitely variable culture of the Web. What follows is a summary of some of the major figures associated with the emerging world of post-Internet art.

Artie Vierkant's Image Objects, 2011 – ongoing

Artie Vierkant's Image Objects, 2011 – ongoingArtie Vierkant's 2010 essay "The Image Object Post-Internet" sparked much of the recent conversation surrounding art after the Internet. In it, Vierkant, an artist himself, surveys the way we engage with images in the post-Internet era, when they can be shared, reproduced, altered, and distributed more easily than ever before in human history. His argument is that in the pre-Internet days, it was difficult to effectively reproduce an artwork because the photographic, scanning, display, and printing technologies we have now simply didn't exist yet; now, the opposite is true. To highlight this shift, Vierkant refers to his own work—Technicolor sculptural pieces he makes with photographic means—as "Image Objects," referring to their ephemeral and infinitely reproducible nature.

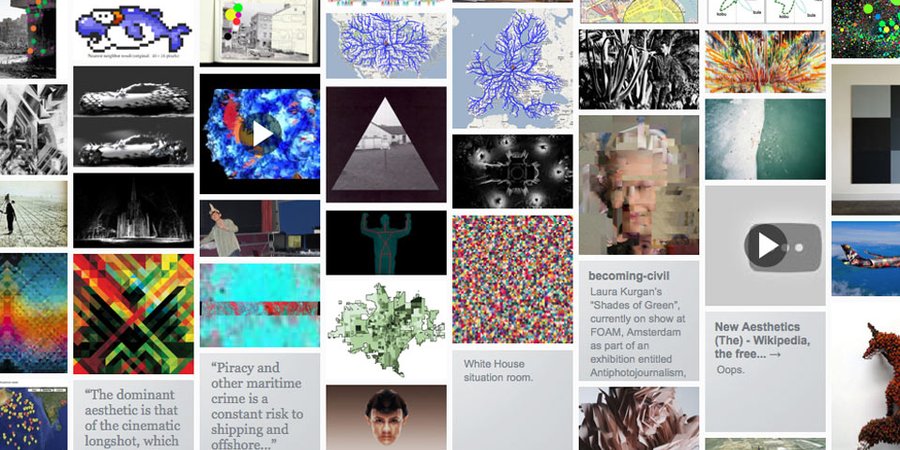

Vierkant's essay is preceded by a number of other projects that, themselves, range widely in content, form, and style. The influential blog The New Aesthetic, run since May 2011 by writer and artist James Bridle, is a pioneering institution in the post-Internet movement. The blog's heady take on online visual culture, imagined as a view of the contemporary from a robot's perspective (a conceit that is quickly becoming more akin to reality than science fiction), has led to a slew of responses, both online and "IRL" (as they say), including a panel discussion at the SXSW in 2012 and the book New Aesthetic, New Anxieties, a critical response to the discussion around the movement. Much of the energy around the New Aesthetic seems, now, to have filtered over into the "post-Internet" conversation.

A sculptural work from Oliver Laric's Icon (Utrecht) project, ongoing

A sculptural work from Oliver Laric's Icon (Utrecht) project, ongoingAnother artist associated with the post-Internet label, Oliver Laric makes work concerned with the Internet-wrought phenomenon of collective authorship and the effacement of the distinction between the real and the fake. In his videos and image-based pieces, Laric displays material he finds online as his own work and invites others to remix, reuse, and re-present it via YouTube and other online channels. Like Vierkant, Laric's work also extends to discursive projects: he used to run the highly influential website VVORK (with fellow artists Aleksandra Domanovic, Christoph Priglinger, and Georg Schnitzer), which set examples of recent artwork in one-to-one comparisons with historical pieces, all sourced online.

While writers, bloggers, critics, and curators attempt to get a handle on post-Internet art, artist keep trucking along, doing their own thing both online and off. Los Angeles-based Petra Cortrightis representative of the many artists who make work specifically for online formats, creating animated GIFs, YouTube videos, and labyrinthine web pages that, in combination, present her compelling take on the newest aesthetic trends—while also somehow managing to treat current visual culture with nostalgia, emblematic of the Net age's constantly-updating, blink-and-you'll-miss-it progressions. Other Web-based projects that investigate how images operate online include Jon Rafman's popular Tumblr project 9 Eyes, for which the artist spends hours sifting "step-by-step" through Google's Street View function to find surprising, resonant, or simply beautiful stills that have accidentally been captured by the Google car's 9-lens, 360-degree camera.

Jon Rafman's 9 Eyes, ongoing

Jon Rafman's 9 Eyes, ongoingOf course, both Cortright and Rafman also produce real-world artworks, objects that can be hung on the wall or placed on a plinth in a gallery; the most counterintuitive aspect of the post-Internet label is that it extends to work in the traditional formats of painting and sculpture. In fact, one of the features that distinguishes post-Interent art from the "Net Art" of the late '90s and early 2000s is its ability to crossover between online and offline formats. While Net Art refers to art that uses the Internet as its medium and cannot be experienced any other way, post-Internet art makes the leap from the screen into brick-and-mortar galleries.

Seth Price's Double Hunt, 2007, a replica of a cave painting from the famous Lascaux caves in France screen printed onto a sheet of PVC

Seth Price's Double Hunt, 2007, a replica of a cave painting from the famous Lascaux caves in France screen printed onto a sheet of PVCSeth Price, for example, is a post-Internet artist whose inkjet prints, vacuum-formed assemblages on high-impact polystyrene, and multiple iterations of the 'same' artwork with only slight variations question the status of objects within 21st-century media's distribution systems. Price has also attempted to manifest the viewing experience of YouTube in real gallery space, as in his 2011 show at New York's Petzel Gallery, where he installed his videos on monitors within individual viewing booths with video playback controlled by the viewer—harkening back to the viewing devices of the early days of cinema and the return to solitary viewership that the internet has brought on.

Cory Arcangel might be the best-known artist associated with post-Internet art that physicalizes immaterial digital structures—and he's certainly the only one to have had a solo exhibition at the Whitney at the age of 33. Arcangel is celebrated for his modifications of popular video games, a series of which were on view in that show; he also reuses appropriated gradient patterns from Photoshop, YouTube videos, and other bits of digital pop culture to craft prints, drawings, musical compositions, videos, and performance works.

The transmutation of art that's based on the Internet from online-only platforms to materializations in real life leads to an interesting question: what will this work look like 100 years from now, when the technologies that these artists are using, commenting on, and imitating either no longer exist or have been radically transformed? Only time will tell. Post-Internet art is distinctly of the now; and that quality, so far, is its most definitive feature.

RELATED ARTICLES:

Secrets to Post-Internet Success From DIS's Scary Berlin Biennale

Post-Internet Phenomenon Nicolas Party on the Importance of Painting Cats in the Digital Age

The Early Disruptors: 7 Masterpieces of '90s Net Art Everyone Should Know About