As an art audience, we have a responsibility to pay special attention to the commonalities that emerge among our artistic contemporaries, the better to sniff out the secret currents of our era and puzzle over what they might tell us. Enter a group we’ve been thinking of as the Frictionless Painters, a gaggle of young artists from Europe and the U.S. whose ranks include Avery Singer, Louisa Gagliardi , Sascha Braunig , Jordan Kasey , and Nicolas Party , among others. United by a shared approach to the figure that takes as much from digital modeling as it does the history of painting, these emerging artists are creating a body of fascinating, striking pieces that render human bodies and faces as near-anonymous, silky-smooth 3D masses that appear strangely hollow despite their heavy shadowing. Though they may evoke Botero ’s rotund caricatures or even Picasso ’s post-war experiments like The Source , these figures—who sometimes finger smartphones or gaze blankly into backlit screens—are wholly of our century, like early drafts of video game characters before they’ve been given their distinguishing features. Given their growing presence in epoch-making exhibitions like the 2015 New Museum Triennial, along with definitive contemporary painting surveys like Phaidon’s Vitamin P3 , we think it’s time to take a deeper look at this emerging style.

Pablo Picasso,

The Source

, 1921

Pablo Picasso,

The Source

, 1921

We should note that the artists mentioned above don’t constitute a “movement” in the manner of something like Cubism or Abstract Expressionism , forged by a group of friends and rivals in the bohemian bars and coffee shops of a major city as a revolt against the prevailing aesthetics of the day. The internet makes such physical proximity and one-on-one communication redundant, and postmodern thought frames the notions of the historical progression of art as distasteful at best. (And besides, it’s not that cool to be part of an artistic movement anymore; observe the pointed disavowals of the term “Post-Internet” by the very artists it was created to describe.)

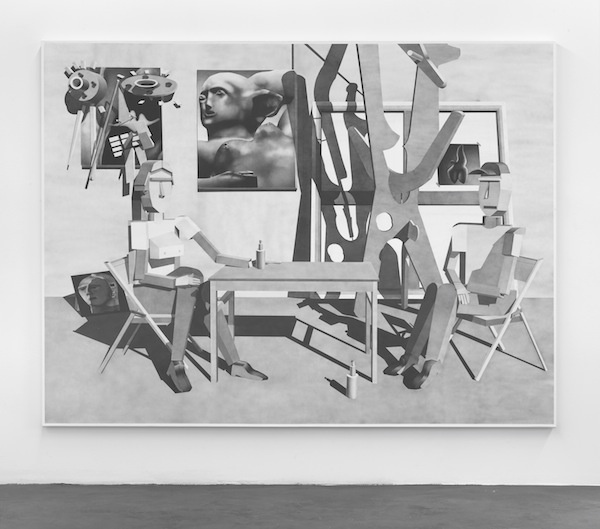

Nevertheless, it’s clear there’s something afoot with Frictionless Painting. Consider, for instance, the recent work of Braunig, where silhouetted human forms struggle to free themselves of a patterned or perhaps gridded field, or Singer’s black-and-white views of an artist’s atelier and other well-trodden scenes, created in the digital modeling program SketchUp and projected onto canvas to be painted. (Both were featured in the 2015 Triennial, to critical acclaim.) Viewed alongside Gagliardi’s listlessly sexual digital renderings on canvas , Kasey’s closely cropped group portraits, or Party’s straightforward depictions of candy-colored humanoids (on the internet, of course—they’ve yet to be brought together in one group show), the commonalities are striking. Though their styles are distinct and instantly recognizable, all share a certain interest in surface-level simplicity, technological mediation, and a just-slightly-off color palette that evokes the ease of fill-effects more than it does surrealist experimentation.

Nicolas Party,

Portrait

, 2014

Nicolas Party,

Portrait

, 2014

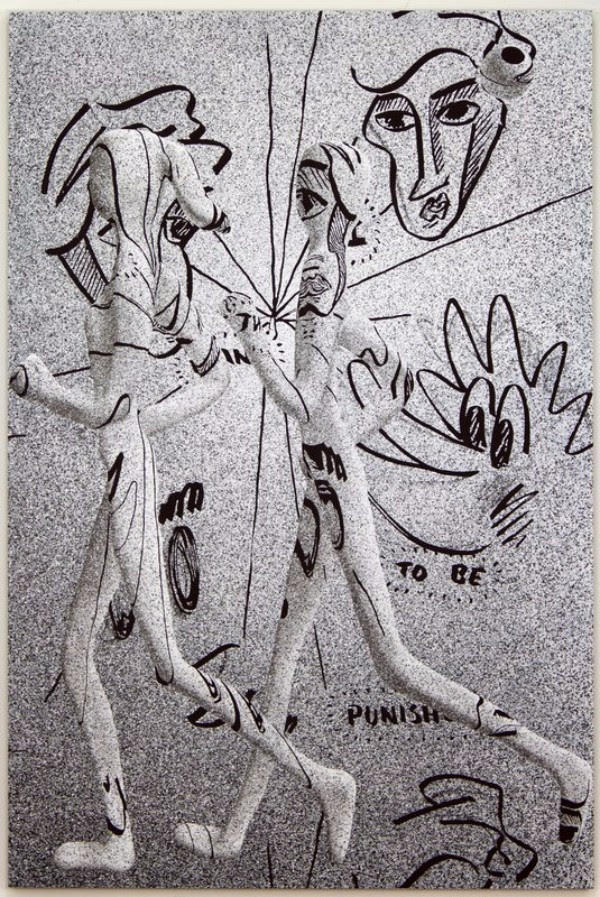

Perhaps the most salient feature is the perceived hollowness of these figures. As Artspace’s editor-in-chief Loney Abrams suggested in a conversation last year with the Swiss painter Nicolas Party , “the figures in [Party’s] portraits are hollow, as if their surface is a hard outer shell with nothing underneath.” She goes on to liken his use of the human body to that of “still-life objects …[like] a vase or an apple,” a comparison that could be readily expanded to include the work of Gagliardi or Kasey, who both specialize in imagery of faces and hands so closely cropped as to appear almost topographical. Abrams isn’t alone in this characterization; the curator Lauren Cornell has referred to Braunig’s figures as “more border than body” and the painter Sebastian Black asserts that his contemporary Cole Sayer’s works “have no substrate, no undercurrent, no content to be unearthed. There is only a plane to glide along.”

Cole Sayer,

Untitled (Running Couple 2)

, 2015

Cole Sayer,

Untitled (Running Couple 2)

, 2015

The artists are aware of this apparent shallowness—indeed, it’s partly what they struggle to achieve. Party, who worked as a commercial digital modeler for ten years before bringing his skills to the canvas, says that this “fake, ghostly look” is now ubiquitous as a result of the rise of 3D imagery and visual editing software: “Before, when you saw a photograph of a person, it meant that someone was there and someone else took a picture. Now, of course, there is no way to know if that person ever existed.” Of course painting has concerned itself with depicting objects of the imagination since our kind lived in caves, but there’s something very contemporary about depicting this kind of radical doubt when it comes to an image’s ontology.

Despite their explicitly three-dimensional appearance (plenty of shading and shadow to go around here), there’s something oddly flat about these pictures. Of course, there’s another kind of flatness pervasive in our daily lives: the digital screen, particularly in the context of the social media apps and sites that help to structure and inform our daily lives. This slick style has the added advantage of translating well to the digital realm, which can wipe out the subtleties and textures of a painting in the process. (Note also that while the imagery may have a certain planar affect, the pieces themselves don’t shy away from their physicality as paintings. The occasional presence of brushstrokes and other painterly flourishes in the works attests to the talent of the painters and is part of their appeal as art objects, as opposed to digital files.)

These artists are conscious of the importance of having their images online and make their work accordingly; Gagliardi readily admits to a “strong link to social media” in her work noting that her use of light in her compositions “suggests the presence of screens outside of the picture plane. We are alone but never really alone—this digital window through the world is always there.” Party agrees, noting that “nowadays, artists are totally aware that people are seeing their work through screens… That’s just how it is now. I’m totally conscious of that, and I make decisions that I know will work very well in pictures because I also want the show to look good online.”

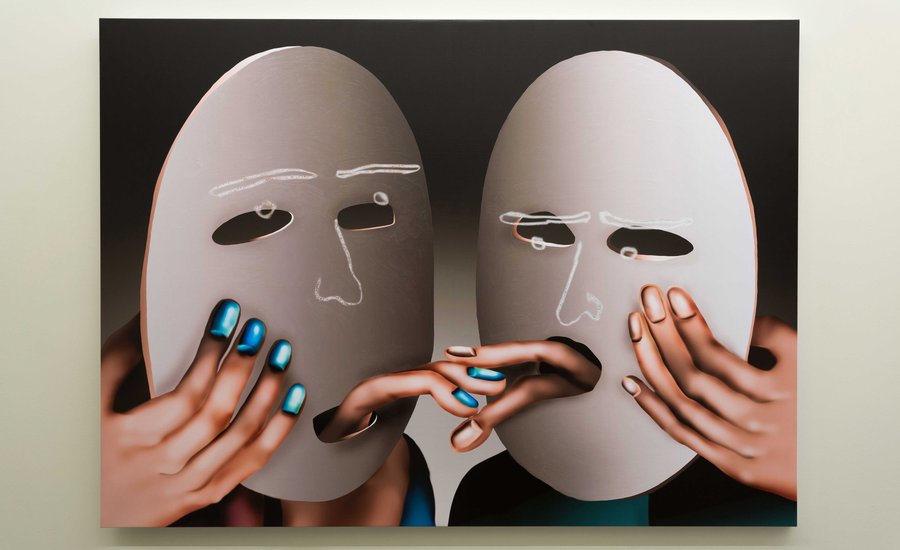

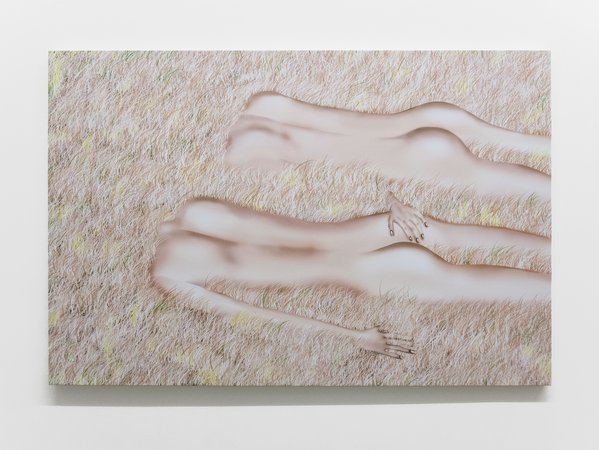

Louisa Gagliardi,

Peach Fuzz

, 2016

Louisa Gagliardi,

Peach Fuzz

, 2016

Indeed, when textures do appear in the work—as works like Gagliardi’s Peach Fuzz from 2016—they seem overlaid on top of the figure in a distinctly digital manner, more of a visual flourish than a physical mass. You can imagine these figures passing directly through such apparent impediments as one would the grass or foliage in video games like Skyrim or Grand Theft Auto. It’s an ongoing theme across these artists’practices: any would-be catching points are (sometimes literally) airbrushed over in favor of a sleek glossiness that can slip effortlessly into a social media feed or curated show.

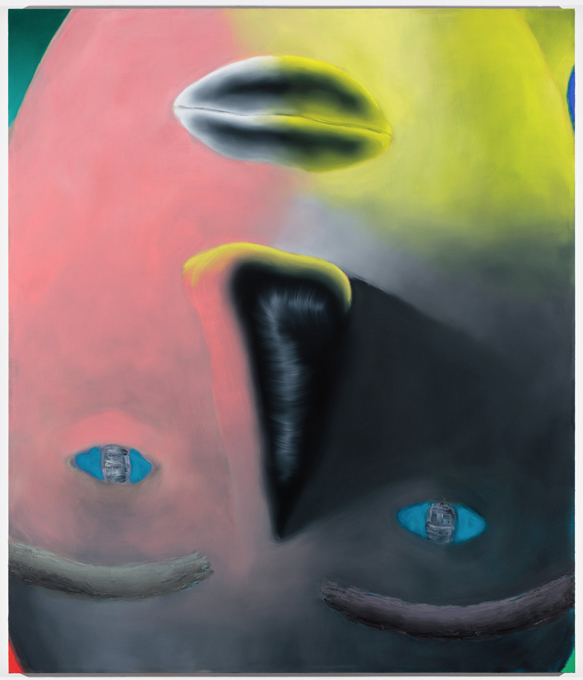

Closely connected to this frictionless surface is a similarly slippery lack of identity. These figures are almost always anonymous, with few distinguishing marks to indicate race or gender and often little in the way of overt personality. These aren’t idealized forms—they’re a bit too simplistic and wonky, like what a Martian would paint if asked to depict an Earthling without having ever seen one. The parts are mostly there and mostly in the right places, but there’s something off about them, something not fully human, like a digital avatar. The visual idiosyncrasies that allow us to identify individuals are conspicuously absent. As Owen Duffy writes of Jordan Kasey’s work in ArtReview, this “basic visual information …accumulates to a portrait of no one.” In the stilted worlds of Frictionless Painting, human beings aren’t really different from the objects they sometimes interact with. These figures have the look of people, but not the subjectivity. Even in pieces featuring multiple figures, there’s a palpable sense of loneliness.

Indeed, there seems to be something of an allergy to identity going around the group. Writing in Art in America , Julia Wolkoff notes that “Kasey’s oneiric realism excludes signifiers for gender, race, and class, and any glimpses of individual identity,” creating a “static, alien view of the present, where scenes of intimacy are opaque and unsettling.” Gagliardi is careful to note that her figures are purposefully androgynous: “As soon as you bring in a gender, it becomes something else. I think this takes so much power from the painting and it is not something I am ready to use. It becomes a symbol right away.” And despite Braunig’s claims that her ghostly outlines are “all sort of stand-ins”for herself, it’s not hard to read them as the most generalized evocation of the human form, literally reduced to an outline. Race indicators are similarly avoided, often by rendering the body in shades of machine grey or bright orange. (It’s worth noting that all of the artists discussed here are white.) At a time when the politics of representation and identity are at the fore of the international art world, it’s significant that these painters seem to largely elide such sticky subjects.

Jordan Kasey,

Upside-down Face

, 2017

Jordan Kasey,

Upside-down Face

, 2017

Of course, there’s another lens through which we can view these works: a reaction to the role of women in the history of portraiture. The majority of the painters mentioned here are female, and the fact that this isn’t particularly remarkable speaks to the ways in which the art world has changed over the past century. Braunig has noted the “long Western history of avant-grade innovation being enacted on the clay of female bodies,” and we can read these paintings as works by women who are reclaiming and updating this process of objectification for their own ends. Seen in this way, the sleekness of these figures can be seen as a kind of defense—there’s nothing to grab onto and accost, nothing to sexualize or fetishize. The figures’ anonymity becomes a kind of freedom.

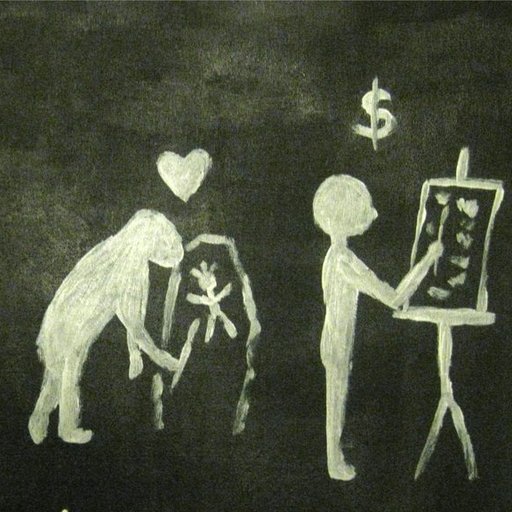

One comment by Avery Singer may be the key to working through these intersecting trajectories. Asked about her compositions by the curator Lauren Cornell, Singer states that her boxy figures are “abbreviated human forms that are meant to convey the process of banalization that occurs through the consumption of our lives through capitalism, and how we might languish or excel in that.” It would appear Singer and her compatriots are within the “excel” camp. As so often happens with visually attractive would-be critiques of capitalism, the system such works are meant to challenge has instead done what it does best: consume, and then monetize for consumption. Capitalism’s capacity for “banalization” is no accident; by stripping away the complex messiness of specificity and identity, capitalist processes repackage subjects as objects fit for consumption, unique enough to covet while maintaining a mass-market utilitarianism to ensure they’re the most appealing to the most buyers. The snag-free nature of the paintings mirrors the need for an unfettered flow of content from screen to canvas to jpeg to collection.

Avery Singer,

The Studio Visit

, 2013

Avery Singer,

The Studio Visit

, 2013

Taken in total, this frictionlessness in both style and content seems to be a reaction to, comment on, and result of today’s art ecosystem, intertwined as it is with social media promotion and conspicuous consumption. There’s no rough edges to snag on, no impediments to the smooth flow of images and capital, nothing to protest against. Like the products and monetized lifestyles that flit by on our social media feeds, these paintings are clean, smart, and fun. It should come as little surprise that, despite their digital origins, each of these painters chooses to present their work in the far more approachable (and salable) medium of paint on canvas. Like Pixar characters made edgy for an over-it-all art audience, these are masterfully rendered and imminently approachable pieces; they can draw you in just as readily as the screens they mimic. Whether we ought to be asking more of art is, of course, another issue entirely.