With the quick reflexes of a street photographer and the controlling temperament of a Hollywood director, Philip-Lorca di Corcia has made images that are hard to pigeonhole as either set-up or spontaneous. For his early series “Hustlers,” he approached male prostitutes on the street and paid them their usual rates to pose for oddly wistful, Byronic portraits. Later, in “Heads,” he attached a strobe light to a scaffold in Times Square and captured unwitting pedestrians in eerie isolation.

His latest body of work, “East of Eden” (at David Zwirner in Chelsea through May 2), finds him leaning in the direction of more transparent staging. Its hallmarks are carefully posed subjects, cinematic lighting, and overt Biblical references. Cain and Abel, for instance, shows two men wrestling with each other as a nude pregnant woman—an latter-day Eve—looks on.

“East of Eden” is also a particularly American narrative of loss and disappointment, one that nods to John Steinbeck’s novel of the same title and to the financial crisis that began in 2008 (the year diCorcia started the series). While installing his show, he spoke to Artspace about learning to love digital manipulation, using fashion commissions as a springboard, and having "control over the surprise.”

Let’s talk about your inspiration for “East of Eden.” There are many layers, with the Steinbeck novel and the book of Genesis and other, more contemporary stories of paradise lost.

It started at the point of disillusion with the economy. I felt that there was a naïve sense of trust and optimism. Everybody thought they were just going to keep getting rich and buy another car. It was all run by people who took advantage of the situation, and it all fell apart. As we all know, nobody really got blamed for it. It seemed like the loss of innocence, a fall from grace, was one of the hallmarks of the financial crisis.

With most everything that’s exhibited, I could make up some connection between it and the book of Genesis. But I don’t think a lot of people are going to come to the conclusion, “Oh, that must be Adam and Eve over there.” The simplest way that I explain “East of Eden” is: that’s the direction they got kicked out in. It’s not really a literal interpretation.

Of course, you can take your clues from the title, which relates not just to the loss of innocence in the book of Genesis but to the Steinbeck novel. As a matter of fact, I have never read the book of Genesis. I read the R. Crumb comic book version.

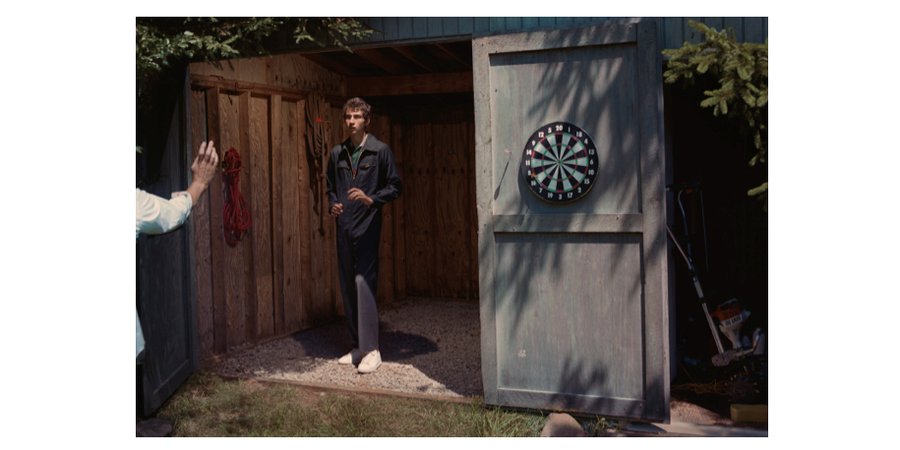

San Joaquin Valley, California, 2008. Courtesy of the artist and David Zwirner

San Joaquin Valley, California, 2008. Courtesy of the artist and David Zwirner

That’s a lot of material to work with—a big, sweeping theme. How did you get started?

The first photographs that were specifically dedicated to this project were of blind people, because someone told me that blind people don’t dream. One of them—it’s not in the show—was of a woman who didn’t dream because she didn’t have an optic nerve. She had never seen anything. There’s a blind couple in the show, a black man and a white woman and their dog.

I almost never have anyone look at the camera. It’s the cinematic way—it’s rare that people address the camera in a movie. Even if I’m working on the street and I’m not directing the people, I can edit out the ones who don’t do what I want. The only picture that I can remember being very conscious of the fact that they’re looking right at me, or at the camera, are the two people who can’t actually see me.

Lynn and Shirley, 2008. Courtesy of the artist and David Zwirner

Lynn and Shirley, 2008. Courtesy of the artist and David Zwirner

There’s a lot of heavy symbolism in this series, which is new for you.

I don’t usually use symbolism in the sense that social reality, however obliquely you approach it, is its own symbolism. It’s actually new for me to be as literal as this is. From the beginning I’ve resisted the kind of photography which I believe gives it away a little too simply.

Strangely enough, this is the least coherent of my series. I didn’t want everything to look like, ok, here are 13 pictures and every one has a pole dancer in the middle. Or the “Heads.” Even the street pictures are in some ways programmatic.

You also use a lot of staging in this series, more than in any of your previous works except maybe your fashion photographs.

I wouldn’t say some of these pictures are any more staged than others that I’ve done. I set up what my intentions are, but then I really do rely on something happening that you didn’t expect. You can call it luck, or anything else. You can’t make that happen.

Here there are two extremes. There’s one image where there’s a pregnant woman who’s naked, and then there are two men embracing or struggling. They’re in the foreground and she’s in the background. They’re wearing red and blue, as the States, I guess you could say. It’s called Cain and Abel. I really had to put that together—find the people who were willing to do it, and all of that.

Cain and Abel, 2013. Courtesy of the artist and David Zwirner

Cain and Abel, 2013. Courtesy of the artist and David Zwirner

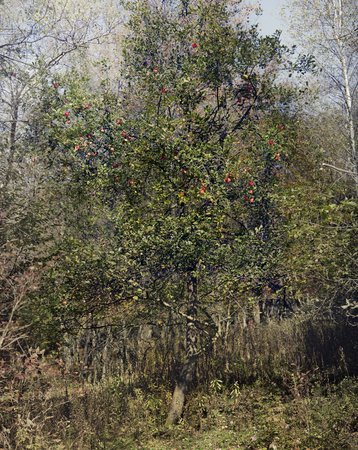

The least planned was just walking through the woods and I suddenly realized that there’s an apple tree, and if I can make it look good—you know, you need an apple, in the story. But I didn’t buy the apple tree, I didn’t pay it, and probably a week later it wouldn’t have looked the same. So I passed it, I got my stuff, and went back.

Upstate, 2009. Courtesy of the artist and David Zwirner

Upstate, 2009. Courtesy of the artist and David Zwirner

I use normal means. Normal—well, they’re antique means at this point. But there’s still quite a lot of stuff done in post-production that changes the graphic nature, if nothing else, of the picture. I had the pregnant woman’s belly button removed, because Eve had no belly button. It took me a long time to get used to the idea of going that far, because I kind of assume that people don’t need to be led quite that firmly by the nose.

Are there other important instances of digital manipulation? In your photograph The Hamptons, for example, two dogs are sitting quietly watching a pornographic movie in a spotless minimalist interior.

That was very early in the game. I thought I needed something to represent the sexual connotations of the loss of innocence. It’s not just biting the apple.

I don’t know why I chose that scene in particular, but it was completely controlled. I had to hire those dogs. They had a trainer with them. They weren’t looking at pornography; actually they were looking at Bambi. I had to go through three different porno films in order to decide which image to use. I got a vintage porn, a contemporary one, and a Japanese animated one. And I had to look at all of them. [Laughs]

The Hamptons, 2008. Courtesy of the artist and David Zwirner

The Hamptons, 2008. Courtesy of the artist and David Zwirner

Another way you communicate the idea of lost innocence is in the golden, sunlit landscapes.

Landscapes in general are new to me. Photographs without people in them are new to me. There’s supposed to be something Edenic—post-Edenic, I guess—about them. Some of the landscapes in this series are maybe idealized a bit, but most of them have something wrong with them. And there are landscapes that aren’t even land—they’re just houses. There are two photographs in which there are no people. Suburban landscapes, I guess you could call them. That was a different way of working, for me. I don’t want to repeat myself.

It’s certainly a departure, for you. There’s more landscape in this series, and a lot less of your street photography.

No, there’s no street photography. Well, there is a new one, that’s done on the street in L.A., but it’s totally staged. That doesn’t count.

The Palace, 2015. Courtesy of the artist and David Zwirner

The Palace, 2015. Courtesy of the artist and David Zwirner

Speaking of your street photography, what was your relationship to the people in “East of Eden”? Where did you find them?

My son is in there, my mother-in-law is in there. Because I was in no particular hurry, I took advantage of situations that were offered to me. In the photograph of my mother-in-law—I consider her my mother-in-law, though I’m not married to her daughter anymore—there used to be a handbag, because I got a commission from Coach. They wanted three or four photographs, to be used in a one-day exhibition in two of their stores in China and Japan. It was hard to refuse.

So that photograph came out of a fashion commission?

That came out of a commission. And the handbag has been removed. It’s more or less an outtake.

Are there other, more general connections between the work in “East of Eden” and your fashion photography?

In order to allow a degree of surprise, I have to set up a situation that is strangely contradictory—I have to have control over the surprise. Sometimes the way to get that, to get the people together, to get the equipment together, to get the whole thing moving, is to take advantage of something that someone’s offered me—a commission or job or whatever you want to call it. I don’t have any problem with that. But I’m not Roe Ethridge—I mean, he’s one of my best friends, but I don’t use the image that was done for the client [in a gallery show].

Frankly, if I’m making a lot of money—which happens rarely—I never get anything out of it. Because that means that you’re working with a big budget. The bigger the budget, the more demanding they are, the less useful it is. The Coach people just handed me this thing, and I got paid to do it too. Photography’s not cheap.

You’ve been working on this series since 2008. How has it evolved?

The financial crisis is, in a way, a bitter memory for most people. But I think the scar that’s left is gross income inequality. To some degree it’s gotten even worse—people have shifted their attention from just wanting to be rich to wanting to be rich and famous. If they could afford it, I’m sure most people would get themselves a Kim Kardashian ass implant. The world has not moved on—they’re just as stupid, just as ready to get taken by the next huckster.

The two pictures that were done in the last couple of months [Genesis and The Palace, both 2015] do involve elements of chance—there’s maybe a greater reliance on mood, as the conveyor of intention or meaning. You could say I always did that. But I think I’m trying to go more in that direction, even though this work is tied down to a concept.

Genesis, 2015. Courtesy of the artist and David Zwirner

Genesis, 2015. Courtesy of the artist and David Zwirner

Is it ongoing, or have you reached a conclusion?

I have a few failed attempts, things I was trying to get done for this show but didn’t for various reasons. I have to move on. I hate this part. I don’t know what’s worse, doing it or finishing it!

Some of the pictures were shown at Zwirner in London in 2013. What was the response over there?

I don’t really know. It was a weird time because I had the “Hustlers” show here, and literally 12 days later the show in London opened with this work minus the newer pictures.

It’s sort of like the people who organize their desk by making a pile, and then they make another pile and they push it where the last pile was, and eventually the pile at the end of the table just falls off. You can either pick it up and go through it, or you throw it in the garbage. I’m the kind of person that throws it in the garbage.

While preparing for the current show, you were winding down a touring retrospective in Europe. What was that like? That kind of experience often puts artists in a critical, reflective mood.

I try to get them never to use that word, the 'R' word. I called it everything—review, or survey, or “selectrospective”—because it wasn’t actually that comprehensive. But it did fill a lot of space, just the same. I had a show at the ICA in Boston when it reopened that was somewhat similar, a survey. I think I threw my back out just looking at it!

You catch up with yourself, and the world catches up with you. When you take things that were done 35 years ago, in a pre-digital age, and put them next to something that was done three years ago—it’s an invitation to criticize what you didn’t know at that time, what other people didn’t expect or do at that time. It’s not my fault that the world caught up with me. I can’t help that. Over the course of my career, the idea of setting things up and even paying people has been established—students do it now. They take loans out to pay their subjects. I know, because I teach.

Mount Ararat, Pennsylvania, 2012. Courtesy of the artist and David Zwirner

Mount Ararat, Pennsylvania, 2012. Courtesy of the artist and David Zwirner

What advice do you give your students in the Yale MFA program? How have things changed, for young photographers, since the days when you were just starting out?

There were very few expectations when I was starting out. I think there were two photo galleries in New York City. At that time it was kind of galling that photo-based work could be described as something different from photographs that were intentionally made. Like the Pictures Generation—that always ticks me off. What a stupid title, what a curatorial wank-off. Pictures are pictures. There’s always this attempt to distinguish yourself from the workaday guy that goes out with three cameras around his neck and a fly-fisherman’s vest.

I came up in an era in which the whole concept of the relationship between photography and art shifted. I think it’s kind of shifting away from that—maybe it went too far. But my complaint with students is that they’re overly aware of things that they’re not really well-educated in. They want to do abstraction, they should know something about abstraction—not just because abstraction happens to be the thing of the moment. I’ve been around for long enough, so I know—it’s going to go. And it’ll come back. And it’ll go. The idea that people are lauded for doing something ahistorical—that never happens. I don’t think there’s anything left that hasn’t been bowdlerized by art students.