On the 36th floor of a Midtown Manhattan skyscraper, the architect Peter Marino marshals dozens of designers to carry out some of the most luxe building projects the world has to offer. There are “war rooms” scattered around the duplex office space dedicated to his different clients; one, empaneled in quilted black, is dedicated to a new Chanel flagship; another is for Dior; a third is devoted to La Samaritaine, the venerable Paris department store Marino is rehabbing in “a big restoration, and that’s really fun,” he says.

The floors are scattered with swatches of luxurious materials, from marble to high-gloss leather, all possible accoutrements to his famously sleek designs. For visitors who are curious to see the finished projects, they have only to walk a block south to 57th Street, where seven of the poshest stores—Fendi, Hublot, Louis Vuitton, etc.—are Marino’s handiwork. He has similar architectural dominance of Rodeo Drive, New Bond Street, Hong Kong’s Tsim Sha Tsui, and other global luxury meccas.

Sleek, near-Platonic ideals of refinement, these stores convey the fashion companies’ elegant brands. Marino himself, in person, reflects something else: their brute commercial power. Famously clad in a black leather uniform of his own design, with silver skull and claw rings clattering on his fingers, the architect is remarkable muscled for a man in his late 60s, with the biceps of a Tom of Finland pinup and the close-cropped mohawk of a biker-gang capo. Black in every permutation, white, and heavy metal are his signatures.

To this, then add art. Marino has made contemporary art the centerpiece of his architectural approach from the beginning of his career, when he got his start doing commissions for Andy Warhol and his extraordinary circle of creatives and luxury titans, and today few of his projects conclude without the presence of a showstopping piece of art that he commissioned for the site. Around his firm’s office, art is clearly the base note of creativity.

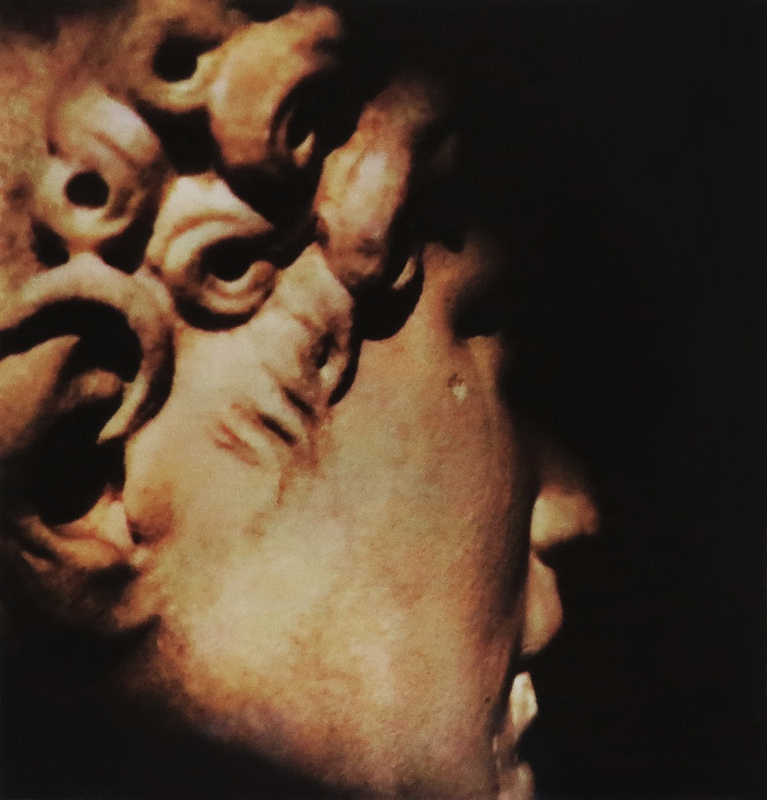

Carved African tribal sculptures (“my absolute favorite,” he says) stand on plinths around his private office like sentinels; Robert Mapplethorpe photographs line his walls, a small fraction of his 142-piece collection of the photographer, the world’s largest in private hands. (A photograph of his daughter, taken by Steven Meisel, was mixed among them on a recent afternoon.) A fuller scope of his taste—which was celebrated in a show of his collection at the Bass Museum in 2015—can be be absorbed around the office.

There is work by Anselm Kiefer (Marino has 12 in his Aspen home), Richard Prince (“I’m very close to Richard because we’re born three days apart”), Antoine Poncet, Thomas Struth, Johan Creten, Arman, Joel Morrison, Nancy Grossman, Vik Muniz, Georg Baselitz, Donald Moffett, Rudolf Stingel, Cy Twombly, Sarah Charlesworth, Damien Hirst, Anthony Pearson, Dan Colen, and Francesco Clemente, to name a few.

In addition to his commercial buildings, Marino is working on a slew of private projects, including a home on top of a mountain in Lebanon and several in the Hamptons and elsewhere for bankers at Goldman Sachs andSafra Bank, and one client he describes as “a rogue bond trader in Mexico.” (“You really do need money to build nowadays,” Marino says.) But one project in particular marries the architect’s themes of art and design: a Chelsea building for the developer and collector Michael Shvo that will feature private residences, a new Lehmann Maupin gallery, and the new art foundation being founded by J. Tomilson Hill, the vice chairman of the Blackstone Group.

Today arguably enjoying the pinnacle of his career, Marino is full of ambitious plans and thoughts about his legacy. He has also returned to his roots, making sui generis artworks of his own. To celebrate the publication of Phaidon’s Peter Marino: Art Architecture, the definitive tome surveying his commissioned art projects, Artspace editor-in-chief Andrew M. Goldstein sat down with Marino to discuss the arc of his life’s work.

Your new Phaidon book just came out, and looking at its sleek, elegant black cover, you can immediately see your sensibility. It looks like it could fit perfectly in any of your buildings—in fact, it looks a bit like the façade of black videotape strips that you commissioned form Gregor Hildebrandt for your Bass Museum show two years ago.

The double black-on-black is just a game we keep playing. Gregor is a great guy. Really interesting artist. You know what you find common about a lot of artists and talented people? A lot of them have a lot of trauma in their life. He had a big illness. He came out of it, thank goodness, and now he’s really great. But I did a restaurant for the French chef Alain Ducasse in Tokyo called Beige, and one day I was sitting and talking to him and he said, “You know, I’m the sole survivor out of six people in an airline crash.” And, I went, “Ok, I need a drink.” [Laughs]

It would seem trauma is an excellent crucible for talent.

It really is. If you just lead your normal, banal life you don’t get enough fried brain cells to be an artist. [Laughs]

No one could accuse you of having a banal life. Today you’re best known as the star architect who invented the de rigueur setting for modern fashion and luxury companies, but what is lesser understood is that way that art has always played a part in your creative DNA. How did that begin? What was your trauma?

I had a childhood disease, so I didn’t walk until I was seven. But I was drawing from a very early age—I had a pencil in my hand and was drawing from three years old. [Laughs] That’s really the origin. I also played piano and made music very dramatically, but when puberty hit I slammed down the piano and I said, “I will never play again. I’m going to be an artist.” [Laughs] When you’re 14, that’s how you are. My mom was destroyed, having worked really hard for the piano lessons.

What kind of art did you do?

I did a special study of art in high school, which meant I had four hours of art every afternoon after school. And I got the gold medal from Mayor Lindsey for a painting I did in 1966. That’s how old I am. I’ll never forget it.It was a series of martini glasses that were cracked and split and glued onto a canvas.

Now, of course, my dad was an engineer. He worked at Northrop Grumman, and I would go in with him on Saturdays and learn about engineering. So, I had a little bit of a head start knowing how to draft and everything—I wasn’t just a crazy artist.

After high school, you went to study architecture at Cornell—a program you chose because it had a pronounced art program.

Yes, I took two years of sculpture, two years of life drawings, two years of painting. I went to university when I was very, very young—I was 16, which is weird. At that point, in the ‘60s, it was still really a beaux-arts education, and it was one of the last of beaux-arts architecture schools. I had a big art portfolio, and I wanted to be Andy Warhol—I wanted to get a commercial art job, like he did when he was making illustrations for I. Miller. But it was very hard. We had an entering class of 60 students, and we graduated 11. It was really unpleasant.

Sounds like another crucible.

[Laughs] Yes. And the 11 of us were all very close. Architecture education is a strange kind of thing. It’s always a good idea to ask architects about their eduction, because, more than any other profession, their education shapes the kind of work you do, because you also have to study mechanical engineering and structural engineering. And those of us who have pulled a little bit out of the crowd always have some ingredients in the soup that are not just your standard architecture education. Mine happens to be a very heavy fine-arts background, and it enabled me to intertwine the two. But then you also have someone like Calatrava, who studied medicine for two years before he went into architecture. These kinds of interesting backgrounds are what make them different, make their buildings more individual.

What’s interesting is that you had this strong fine-art background, and then after graduation you went to work for Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, which was famous then for building the Sears Tower in Chicago, the tallest building in the world. Clearly you weren’t messing around. What was that experience like?

I was very fortunate. I worked there every single summer during college. The first summer I started as an office boy, delivering mail; the second, I worked in the model shop; the third, I worked in the interior shop; the fourth, I did architecture. Finally, after college, I worked there as a full architect. It was a great organization, so well-run, so professional. I was there during its heyday, working for a firm that had just done the Lever House and Hirshhorn Museum and invented curtain walls. Whoa, dude. Forty years later, we’re still building curtain walls. The technology has modified, but basically we’re still doing 50 years later what SOM did in the 1960s.

What did you learn from SOM?

I think I learned how to organize an office, oddly enough, because, coming from a somewhat artistic background, it’s not my natural inclination. But I was so young, and I got imbued with how an office should be run. Now we have an interiors department, too, we have a model shop, and I realized everything is unconsciously based on SOM because it just seemed natural. Of course, we’re not engineering-advanced enough here to ever compare with SOM. This really is a heavy art-and-creativity place. When you come here, you know you’re in the “Art Architect”’s house.

How did you fit the culture at Skidmore, Owings & Merrill?

I didn’t fit into any culture. I was a student like the interns we have here right now outside my doorway. I was never a power-suit guy. I rode a motorcycle in college, and when I worked there in 1970s it was about the bellbottoms and seriously long hair. [Laughs]

That’s amazing—you were a hippy.

Well, I had motorcycle boots, so I don’t know what kind of hippy I was.

You mentioned that Andy Warhol was somebody whom you aspired to be like in school, and it was during this time that you started to enter his world. How did that happen?

Well, Cornell had a program where in you fourth year you could study in New York in an office on 17th Street and Union Square, which was run by a very good architect name Rolf Ohlhausen. So I did that, and it was fantastic. The Factory, of course, was at 45 West Union Square, literally across the street. Max’s Kansas City was also literally across the street, and I went there and met everybody. It was a great moment. Looking back, it’s crazy, because people say, “How did you know to go to Max’s Kansas City?” And I didn’t. It was just the hamburger place across the street from the entrance of my school, so I went there because you could get a hamburger for $1.19, and there were really cute waitresses, and, you know, it seemed artistic and fun. [Laughs]

Max’s has become legendary as the era’s great watering hole for musicians, writers and artists, Warhol chief among them. Did you communicate with any of these guys on an art level?

I was a student—it would have been really pretentious. No, I just soaked it all in. But the Cornell program took us to everybody’s studio. They took us to Roy Lichtenstein’s studio, they took us to Claes Oldenburg’s studio, they took us to Larry Rivers’s studio, and, of course, to the Factory across the street. It was a great program, but that was the year—1969—that the Afro-American Society took over a campus building and set cars on fire and shut down the university. People forget how violent the student revolutions were in ‘69. It was really a vivid moment. Because of that, we were the last class that was able to do the New York program.

After graduating, you began working at Skidmore, Owings & Merrill full-time. At a certain point, you met Pat Hackett, the editor of The Andy Warhol Diaries, and you entered his circle. Soon you were doing projects for Andy. You designed the third incarnation of the Factory, years after Warhol was shot in his previous studio. You also designed his townhouse. How did this all happen?

Andy was living with a guy called Jed Johnson, and Jed said, “Peter, Andy just bought a house on East 66th Street, and needs to renovate the bathrooms and kitchens. We’ll need a lot of work done.” The house was pretty shabby, so I did a set of architecture drawings, and Jed did all the interior decoration, and it was a really good experience. For a young architect, it was very exciting to do the drawings for Andy’s townhouse. The house was built in 1920s, so he wanted the bathroom, kitchen, and everything else to look 1920s. He said, “I want this to look untouched.”

It was a wow. I said, “Really? You don’t want something groovy?” And he said, “No.” With the Factory, it was the same thing. Jed said, “Ok, Andy has to move because he lost the lease at 45 West Union Square, and he’s going to 860 Broadway, so we need walls and lighting and painting racks and a meeting room and this and that.” Because they had about 20 employees at that point, and they had offices for Interview magazine. That’s how I met a lot of people.

Was there any element of luxury in the Factory?

Well, always in the furnishings and the paintings. Remember, Andy was a real trader. He would trade some paintings and he would trade some other things and suddenly there would be a wonderful Roy Lichtenstein on the wall, and I would consider that real luxury. Andy was also a big buyer of antique furniture. He bought a lot of Art Deco of very high quality, and he loved early American antiques. He had this thing from growing up in Pittsburgh, and he’s always say, “Early American stuff is the best.” And, I’d go, “Really?” Because I knew nothing about that.

But I drove down with him and friends to places like Winterthur and looked at all the American museums, and he was fascinated by it, quite a connoisseur of American furniture and also European furnishings. He had definite tastes, and all of that was luxury, but presented in a studio way. There were scrubbed floors with no finish, and after you put spackle on the walls to fill in the nail holes, and he would say, “Oh, just leave that—please don’t bother painting them.”

The famous story is that I teased him—because he was famously close to the nickel—and said, “Andy, is that the way you get to save two coats of paint on. Are you kidding?” And he said, “No, no, I like the way the spackle looks.” Of course, he was right—it did look amazing. But he walked in one morning and said, “Doesn’t it look pretty?” and I said, “No, it looks unfinished.” Because I thought it wasn’t sophisticated enough.

In 1978 you opened your own architectural firm, Peter Marino & Associates. You began designing homes for clients like Gianni Agnelli and Yves Saint Laurent, but you also kept a foot in the Warhol circle. You worked with Warhol’s manager, Fred Hughes, is that right?

Fred Hughes was my first major client, because when Andy had moved out of 1342 Lexington Avenue and moved into East 66th, Fred got the Lexington Avenue brownstone that Andy had lived in up until that point. Part of why Andy moved was because his mom had lived there in the house with him, and after she died it was too sad for him to live there anymore. Plus, he was doing very well, and the house on East 66th was a definite step up. So when his manager Fred took over 1342—half he purchased and half he got in commissions—he said, “Now, Peter, please do this for me,” because I was in the group. That was the first independent job that I did on my own. It took me about a year and a half.

You’ve said that doing Fred Hughes’s house was an even bigger break for you than Warhol’s. Why?

Well, Andy never showed his townhouse to anyone. His private life was exactly that. So everyone would say, “Oh, I’m sure when people see Andy’s house your career is going to take off.” But nobody really saw the house until he died in 1986. I would say less than 20 human beings on the face of the earth saw it. It didn’t help. But what helped was that people knew I did it, and what helped even more was doing Fred Hughes’s house, because as the manager he entertained lavishly and invited everyone over because he was the one who would bring people like Mr. Saint Laurent to Andy and say he wants a portrait done. He was the connection to the outside world, and his house that I did, everyone saw.

What was the aesthetic? What did he want for his house?

It was interesting. It wasn’t that different aesthetically from Andy’s, because he was always with us on the buying trips. He had a wonderful collection of Baltimore painted furniture from the 1820s and ‘30s. Early American things. Art Deco. He had a wonderful Japanese 17th-century Buddha in the entrance hall. He also had some fantastic Modern paintings, but those boys loved 19th-century American paintings. They liked Pre-Raphaelite paintings. And, of course, because they traded with other artists, they had very good collections of all of those artists too. Now we look at them as masters, but in the ‘70s they were still considered jokes by a lot of people. We think, “Well, yeah, Pop art. Duh! So obvious.” It wasn’t always so obvious.

Sounds very traditional.

The aesthetic was very much a correct New York townhouse, and that was a good historic discipline. If you’re an architect like me, doing these early townhouses and getting them historically and aesthetically correct is the equivalent of a musician playing Bach for 30 minutes before they go onstage. And they looked beautiful. I was not at the point to say, “Ok, let’s blow the townhouse out and make a brave new world.” That’s not the way I began my career.

Where did your career go from there?

Well, from Fred Hughes my career took me via him to Vincent Fremont, Bob Colacello, and all of the people at the Factory. I really met the world—and where else would a kid from New York meet the world? I mean you don’t meet a Rothschild by crossing the street. [Laughs] You don’t meet Gianni and Marella Agnelli by going to work every day. You don’t meet Mr. Saint Laurent and Pierre Bergé—you only meet them through the artists. Everyone from Europe was coming to New York to see the art scene. And it was a double whammy. The kids today don’t remember the violence of the Red Brigades in Italy, but the communists were thisclose to overrunning the whole country. So all the cultured, wealthy, sophisticated people came to New York. It was a very frightening moment.

And they all needed a place to stay.

And they all needed places to stay in New York.

Enter Peter Marino.

Right place, right time.

READ PART 2 OF THIS INTERVIEW

Peter Marino on What Contemporary Art Can Do for Fashion's Bottom Line