A naturally elegant and precise draftsman, the Berlin-based Brit Paul McDevitt has a somewhat perverse relationship to his talents, preferring to challenge his own well-trained hand with cartoonish figures, rough-hewn collaged elements, and graffitti-esque marks. Since his emergence onto the London scene in the early 2000s, he has also found ways to push drawing beyond its typically solitary confines—expanding it into a collaborative, multi-disciplinary approach that branches into publishing, music distribution, and curation.

McDevitt spoke to Artspace about his new show at Stephen Friedman Gallery, his complex relationship with the British modernist Henry Moore, and his habit of reaching for a drawing pen and paper before his smartphone.

I thought that we could start by talking about your draftsmanship. You’re extremely proficient, on a technical level, but it seems like that isn't valued in today's art world. Do you feel like your skills are underappreciated?

It’s hard to say. With painting I think you certainly see more realism at the moment—there seems to be a lot of slick, hyper-real paintings that are coming around now. With drawing, I think it probably just comes in and out of fashion more than it ever disappears from people’s work. I don’t think one should be too excited about proficiency—it’s as frustrating as it is satisfying to make work like that. For me, I reached a dead end. What was I doing, making these really time-consuming drawings that I knew wouldn’t get any better? That kind of proficiency is kind of an endgame in itself sometimes. It’s very time consuming as well.

On the other hand, there’s a lot to be said for seeing the artist’s hand in the work. I value that more and more because there are so many fabricated products out there. There’s something appealing about seeing a work where you can see the artist’s every gesture. I think with a drawing, especially, there’s nowhere to hide. Unlike a lot of materials, with drawing you can’t build up layers. Every stroke and every breath is there on the surface. I still get a kick out of that. I just don’t know that it has to be these really time consuming single pieces. I’m more excited now about quicker pieces with faster gestures.

Is this the kind of work you’ve been doing recently?

It took me a long time, but I realized that if you make things bigger, it’s actually quicker to do them. It’s usually making smaller works that gets you right down to the surface, nose to the paper, as it were, and getting lost in details that aren’t always even appreciated. To avoid this I’ve been working on a few series of works recently, rather than thinking of them as individual pieces.

Over the years I’ve also done quite a few collaborations with other people, as a way to not know what the drawings will look like in the end—to have an element of chance or surprise. When you plan out these really detailed drawings, a lot of time you can know what it’ll look like when you’ve just started and you can spend days coloring in, getting the results you had in mind in the first place. There’s not much surprise or risk in that.

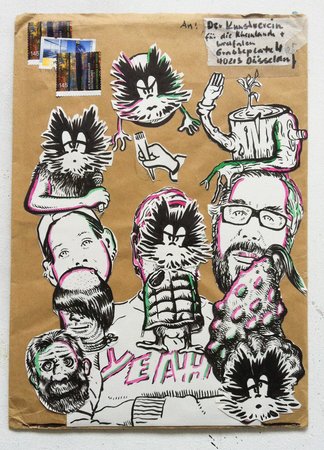

Untitled, 2014, (with Cornelius Quabeck). Courtesy of the artists and Stephen Freidman Gallery

Untitled, 2014, (with Cornelius Quabeck). Courtesy of the artists and Stephen Freidman Gallery

I’m glad you mentioned collaboration—it figures into a lot of your work, including your 2009 show “Bierstadt” with Cornelius Quabeck at Stephen Friedman as well as your DIY publishing effort "Hunker Down" currently ongoing at Peter Scott Gallery. What attracts you to the collaborative process, besides the element of surprise?

One obvious thing is the communication—any of the work that I do is just me alone in the studio, and as much as I value and need that solitude, it’s really nice to talk through things with somebody else once in a while. You get to an end result much quicker when there are two people—you can get four times the amount of work done.

Collaboration can be harmonious, but more often than not it’s a combat. But losing that sense of being precious about the end result, knowing that any minute your colleague can just paint the whole thing black and obliterate everything you’ve spent an hour doing—I think that’s really healthy. I’ve been able to maintain a few of these dialogues now, and not just in making drawings. I’ve made drawings with Cornelius Quabeck, who also shows at Stephen Friedman Gallery, but we’ve moved more into book-making these days.

You and Quabeck have maintained a very productive partnership over the past several years. How do you work together, and why have you started moving into book production?

It started with us realizing that many of our concerns are similar. He lives in Dusseldorf and I live in Berlin, so even though we’re in the same country we’re not very close—we're about five hours apart by train. A lot of what we were doing was in short bursts when we would see each other, or by mail. The latter works ended up being a lot of drawings on envelopes being sent back and forth, letting the creases and stamps and marks of the postal system become part of the image too.

There were two reasons that we started making books: one is that a book is a good leveler. It homogenizes, in a good way, disparate styles into one format. The second reason is that books are a really nice way to show a chronology. A lot of the drawings we make go back and forth, like a conversation on paper. The order of the book is perfect for that. So we started making books, mainly of our own work to begin with. You know, nobody buys artists’ books, so that’s not the reason you make them. The nice thing about them is that they get out there in strange ways. They’re like a message in a bottle, somehow—they end up in places you couldn’t have imagined before.

You two also run a record label called Infinite Greyscale. How did that come about?

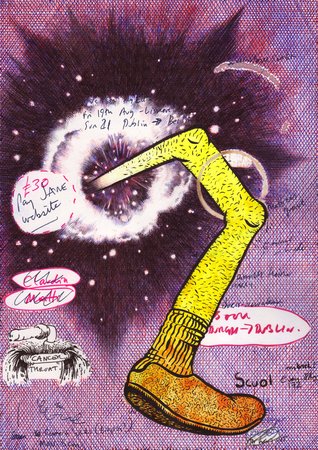

We’re both big music fans—I don’t make music myself, but Cornelius does. We started thinking about having a record label and pressing vinyl. We figured that’s actually something people would buy. We tried to do something that’s half art and half record.

I’ve got this Risograph printer in my studio, which just prints black ink, so it prints up to A3 paper size. It’s not quite big enough to do a 12-inch cover, but it was enough for a 10-inch, so we started pressing these 10-inch records on colored vinyl. They have a single 10 minute track on the A side, and the B side is a screen print. It’s half-music, half-art I suppose. So far we’ve had some very interesting musicians, like Holly Herndon, Jefre Cantu-Ledesma who is in a band called The Alps. We had another guy, Gabriel Saloman, who is one half of Yellow Swans, and we’ve had Jan St. Werner, who’s one half of Nelson Mars. We’ve had some great people so far. We’ve only got six records out currently, doing three pressings a year, but it’s been terrific—it’s a whole new audience for us. It’s been a very satisfying project, and we’re just about breaking even.

That’s great, breaking even!

Yeah! That’s like roaring success when it comes to publishing.

Stara Rzeka's self-titled 10", with artwork by Paul McDevitt and Cornelius Quabeck, from Infinite Greyscale Records

Stara Rzeka's self-titled 10", with artwork by Paul McDevitt and Cornelius Quabeck, from Infinite Greyscale Records

In addition to all this, you also curate shows with fellow artist Declan Clarke, maintaining a loose program under the title Clarke and McDevitt. What’s new in that realm?

“Curate” is not really the right word—we organize projects with other artists. We did a show last year at Sommer & Kohl, a gallery I work with in Berlin. We described a painting by Turner using sculpture. More recently, we did a project with a magazine called Twin, which is one of those big, glossy, half-fashion half-art magazines. That was for an issue themed around youth last year, so we printed lots of artists’ invitation cards from their first shows. It was very simple, but it was nice to see all of this ephemera that you don’t really get anymore. No one really makes invitation cards.

When working on these collaborative projects, how do you iron out disagreements?

Honestly the easiest way to work it out is just to do no editing, to just show everything that was made. You hope that the energy comes through. A lot of times there are works that one or the other of us hates, but I don’t think that’s necessarily a reason to withdraw a piece. Even if there’s a piece that we got really frustrated with and crumpled into a ball, that often goes into a show as well. I have to say we’ve gotten a little more careful over the last years—a little less reckless, a little more tidy. That’s probably why we’ve switched our attention to publishing at the moment.

What is the nature of your relationship with text in your own work? I'm thinking especially of your “Notes to Self” series from last year.

I’m not so comfortable with using words, funnily enough. I don’t like my handwriting, so the “Notes to Self” are actually just pieces of paper that I keep notes on. They pile up over the months, and then at some point I look over a bunch of them. I’m really distanced from those notes by the time I start drawing on them—all that text was never intentionally part of an artwork. It’s like collaborating with an earlier version of myself. There’s something on the paper to respond to already, so the text is the base layer that I draw over. They’re traces of something graphic more than vehicles for linguistic meaning.

Notes to Self: 14 June 2011 (ii), 2011. Courtesy of the artist and Stephen Friedman Gallery

Notes to Self: 14 June 2011 (ii), 2011. Courtesy of the artist and Stephen Friedman Gallery

I see your works as referencing a lot of different art historical styles and movements. If you had to nail down just a couple of the biggest influences on your work, what would they be?

I’ve made a lot of works that refer to Henry Moore and Piet Mondrian over the last few years. I think Moore specifically is someone I kept returning to because he’s from my hometown, Leeds, in Yorkshire. He was part of the landscape when I was a kid. It was something that you grew up with without having ever been told it was art. As an adult I started to get interested in the emptiness of Moore—this was a figure that represented British modern art, even in caricatures and cartoons. When I started to think about it, I had no idea what Henry Moore was. Was he a surrealist? Where do you place him? It’s difficult. He was just part of the background noise somehow.

This openness, meaninglessness of Moore was something that I explored in a lot of works. I used his sculptures as cartoons or avatars. I even made some bastardized versions of Moore sculptures out of wicker. I was thinking about how to translate the drawn line into three-dimensional form, so I thought it made sense to make a sculpture out of line, to literally cross-hatch in space. All the balance and finesse of Moore was missing—they were all top heavy or clumsy versions, unheroic and unmasculine in many ways, versions of seven-ton bronze sculptures that you could pick up with one hand. Those were in an earlier show at Stephen Friedman Gallery, called “Solitary Figure."

What about Mondrian?

My interest in Mondrian started off with my childhood love of comics. I still like comics, and Mondrian panels looked very much like a comic book page, all these different panels within a form. I started thinking of these works as a way to use narrative in a painting or drawing. In a way, I think of Mondrian’s life as a kind of narrative of the 20th century in itself. He started off wearing a smock in a dark garage studio, painting trees in the countryside. By the end of his life, he’s living in New York. There’s the silence of the countryside, but at the end of his life he’s living in the city, listening to jazz, everything is white, it’s noisy, and he’s painting in geometric forms. The whole transition from rural, pastoral life to urban modernism is illustrated in his practice.

Having worked in both cities for a number of years, what would you say would be the biggest difference between the London and Berlin art scenes?

Money. There’s no money here. It means studio and gallery space is cheap, it means all the artists are here, it means you don’t have to ship everything in, but it also means there’s no one to buy it. There are a lot of galleries here not making money. It’s in constant flux, but the major thing is that money isn’t king in this town, unlike London or New York, so there’s a whole space for something else in this city.

What is that something else? What’s so attractive about Berlin, if not the money?

I think it’s still rather lawless. It’s a city that in modern times has been founded on a certain loosening of the laws, a certain sense of civil disobedience. That’s why Berlin is what it is, because they had West Germany abolish military service so they would have people come to West Berlin to keep it populated when it was an island in the East. They scrapped the licensing laws for bars so places could stay open all night, things like that.

That sort of chaos and anarchy is still here, as much as the place is being gentrified. It means you can still do things that you can’t do in London. You can find a space here and turn it into a studio, open a gallery in it, or turn it into a bar. No one really cares. You’re not going to be clamped down on by the authorities within minutes of opening the door. I think that’s still something that attracts a lot of people here. It can be a really hedonistic place and it can be hard to work, but you can achieve stuff. You can have a headspace and the freedom to do things that are very difficult to do in other cities. It’s a healthy environment, I think, as long as you don’t have to find a job. It’s a kind of paradise.

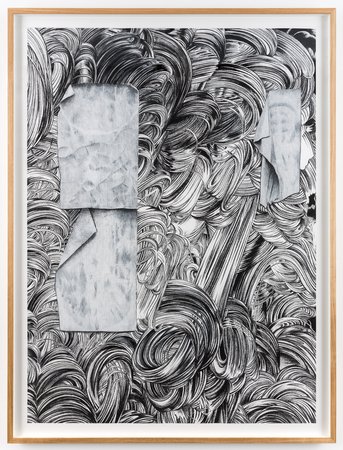

₥or₪i₪g ₩i₪€, 2015. Courtesy of the artist and Stephen Friedman Gallery

₥or₪i₪g ₩i₪€, 2015. Courtesy of the artist and Stephen Friedman Gallery

What can you tell me about the new works at Stephen Friedman?

The new work is actually pretty simple. When a UK High Street shop closes, they often paint the inside of the window with buttermilk, white washing it so you can’t see in from the street. It creates these big white gestural abstract markings. They’re the result of somebody trying to cover the biggest space possible in the quickest time, so they’re unconscious gestures, but you see them more and more throughout the UK.

It’s not surprising, because the British High Street embraced capitalism to a degree where every town looked the same, with the same dozen franchises and big brands. There was nothing independent in any city center. These closures are depressing, but at the same time you’re not being assaulted with ads all the time. There’s a lot less product placement as you walk around—instead there’s this weird painterly gesture. I’ve really responded to this, and started making my own compositions with these gestures, taking photographs and collaging.

Like a lot of people, my fantasy when I was younger was to be the kind of painter that that made big abstract paintings. It’s not an easy thing to do. Drawing is so ingrained in me that even when I would try to paint on canvas, I would actually just be drawing with a paintbrush. I would hardly call it painting—it was stabbing at the canvas. Over the years I started appropriating found gestures and using those to make images that are about painterly gestures. It’s about failure or ambition and all these other things too, but it’s not actually an abstract painting made with paint.

They remind me of Lichtenstein’s Brushstrokes.

That’s something that I was thinking about. They’re of similar scale to a lot of Pop art from the 50s and 60s, but I was thinking about these as 21st-century Pop art, where things didn’t really work out and the shops are closed and this is what’s left of the display. I called the show “Grand Canyon,” to suggest a void or something that’s missing in the heart of the town, in the heart of the culture.

It’s interesting that you’re using drawing to get at these different mediums, whether it’s sculpture or painting. You’re trying to understand these other mediums through your drawing practice.

I tried to fight against this before, but what’s the point? If I’m left alone for half an hour, I’m going to draw. I’m going to pick up a pen and paper—I’m not going to touch my iPhone before I draw something. It’s the first thing that I reach for. I suppose it’s how I explore the world a lot of the time.