More and more often, dealers have been looking for new talent not in MFA programs but in the unlit corners of recent art history—very often helped along by artists as their guides. As a result, a new category of emerging artist has come into being: the artist, often over 60, who has worked outside of mainstream recognition for decades, honing a distinctive style that has been allowed to age and ripen out of the light of the art market (in the best traditions of affinage). There were plenty of these artists at the fair, and here are five you should know about now.

MASON WILLIAMS

Alden Projects (New York)

In 1956, Mason Williams drove from Oklahoma City to Los Angeles with his friend Ed Ruscha, whom he’d known since fourth grade, and eventually they got themselves an apartment where the two could launch themselves into the cultural stratosphere. Ruscha was struggling along as an artist at the time, while Williams, who had also gone to art school, had dreams of translating his creative vision into television.

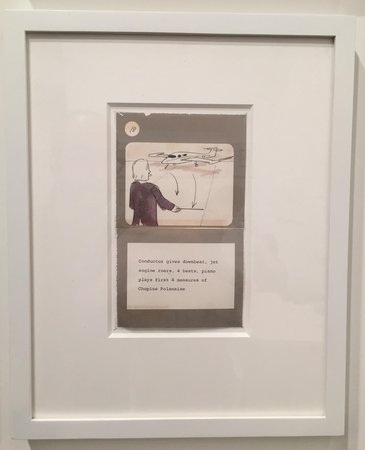

He had an in at "The Roger Miller Show," so he helped his roommate out by tossing him a gig as the illustrator of storyboards that the two created as candidates for the show’s “cold open” sketch. They were clever, like the above sketch involving Liberace landing a LearJet, but were all rejected for being too expensive to produce and too outlandish. From there, Williams dove into the entertainment world, becoming head writer for “The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour” and later (briefly) for “Saturday Night Live,” penning songs for the Kingston Trio, composing “Classical Gas” (the biggest easy-listening radio hit ever), and even giving Steve Martin his first gig, but he never left art behind.

In fact, he dove into printmaking as a side pursuit, creating a giant 37-foot scale print of a Greyhound Bus—which was bought by MoMA in 1968—and also collaborating with Ruscha on several major prints, including the iconic Double Standard of 1969, which the Modern also acquired, and the book Royal Road Test. (Williams also tried to bring artists like Claes Oldenburg and Robert Smithson onto “The Smothers Brothers,” but the brothers thought he was crazy.)

Now 77, he lives in Eugene, Oregon, and after a widely successful career in show biz, is being reborn as an emerging artist. Two exhibitions of his work at Alden Projects this fall were critical hits, and his booth at NADA sold out in the opening hours.

ALICE MACKLER

Kerry Schuss (New York)

A New York native, Alice Mackler worked for years as an office manager in the city before getting a degree at the School of Visual Arts when she was in her 60s, and in the quarter century since she has been quietly making small, somewhat lumpen sculptures of women that hum with a deep intensity of feeling. A few years back, her neighbor, the painter Joanne Greenbaum, discovered her work at a local pottery sale, introduced it to Amy Sillman and other fellow artists, and since then Mackler’s work has become a sensation, landing her a spot in the Jewish Museum’s current “Unorthodox” show. “Talk to younger artists and they’re all crazy about Alice Mackler,” said her dealer Kerry Schuss. “She’s emerging at 84.”

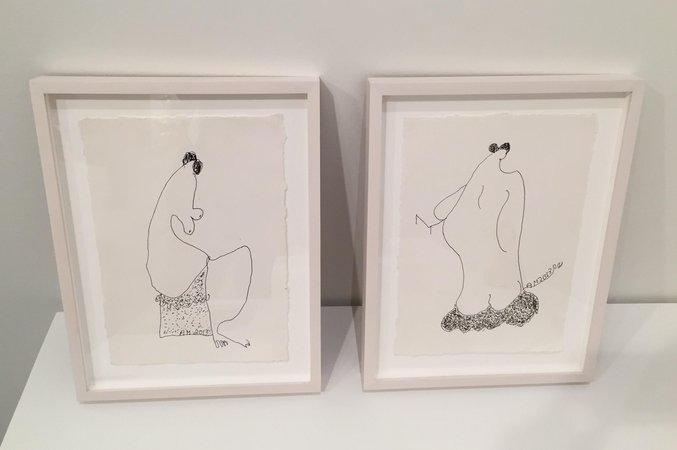

In recent years, Mackler has begun making collage paintings built around women’s fashion ads, and ink portraits of women that she draws from life, using hired models. “The female figure is very much her topic,” said Schuss, who added that Mackler identifies with artists like Louise Bourgeois and Niki de Saint Phalle. A very private person who doesn’t reveal much about herself, Mackler doesn’t use email or even a telephone, requiring all correspondence to be done in person or by snail mail. Her deliberate distance from the art world may have helped her work, Schuss said. “It’s good that recognition didn’t spoil her,” he said. “But she had the stubbornness of a true artist. You just keep on going—you just got to do it.”

Now, however, that limelight has descended in the market—her sculptures ($6,000 to $12,000), drawings ($1,500), and paintings (around $3,000) were selling like crazy at the fair—and curators have been sniffing around, including one director of a new Virginia museum who came by the booth expressing interest in doing a show. “It's easy with this stuff I'm telling you,” said Schuss, smiling.

SILVIANNA GOLDSMITH

White Columns (New York)

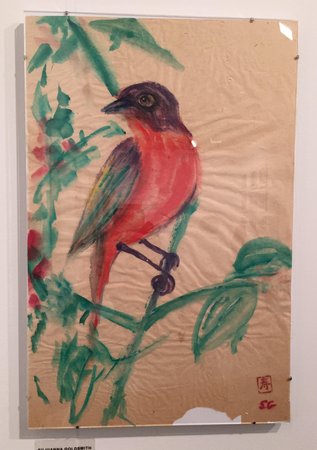

A few years back the young artists Ryan Foerster approached Matthew Higgs, whom he had worked for as an assistant at White Columns, and said, “You should really see my landlady’s work,” Higgs recalled. “We were intrigued.” The woman in question, Silvianna Goldsmith—who is now in her 70s—was not your typical landlady: in the 1960s and ‘70s, she had been an experimental Feminist filmmaker and member of the Art Workers Coalition, creating avant-garde body-based work in the vein of Carolee Schneeman’s orgiastic Meat Joy (1964)—work that was so provocative, in fact, that Kodak refused to print it when she sent it in for developing, forcing her to sue the corporation to get her footage back.

Those films are today housed in the Filmmaker’s Coop, and Goldsmith went a bit underground, remaining in the art scene somewhat (she was close friends with Maria Lassnig, who painted a portrait of her) but only resuming her own art a few years ago when she took up ink painting at a senior center. The tender compositions, displayed at the fair, constitute her first show in decades (though she and Foerster collaborated on a fanzine recently that White Columns published). Priced at $500 per, they were sold out at the booth, snapped up by such notables as the dealer Maureen Paley and what Higgs referred to as “one of the most important collections of self-taught art.”

KATHERINE BRADFORD

Adams and Ollman (Portland)

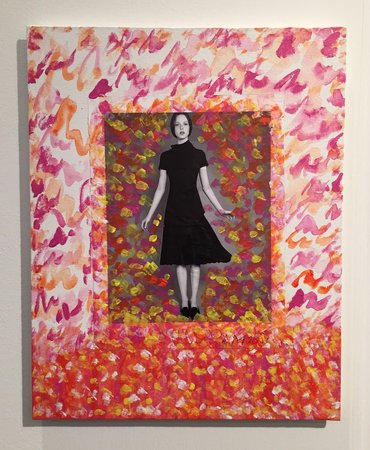

We pegged the 73-year-old New York-based artist Katherine Bradford as an “artist to watch” at NADA this year, and she has proven a bona fide meteor indeed at the fair. Brought by both Adams and Ollman and CANADA (which seemed too jittery about her success to discuss the work), her paintings had lines of suitors streaming out of the booths, with newbie collectors, seasoned advisors, and dealers alike hovering about her art like Beatles fans.

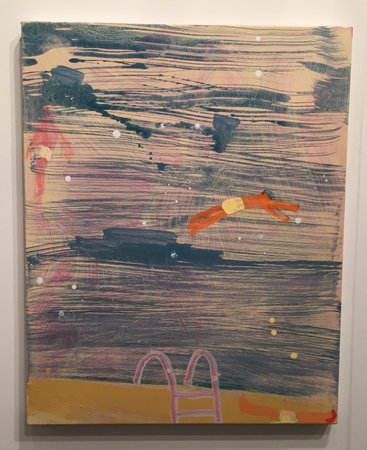

Bradford, it turns out, is another artist whose subtle work eluded market fame for years, but had a devoted following among artists—many of whom she taught at FIT and the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Art over the years—who admire her paintings of ships, swimmers, divers, and Superman for the way they ride the line between super-funny and tragic, awkward and elegant. (Their subject matter is also marked by a state of indeterminacy: are the ships coming or going? Are the divers and swimmers flying or diving? Why does Superman seem so sad?)

Bradford achieved a bump when Adams and Ollman brought her work (priced at $3,000 to $25,000) to NADA New York this year (one half of the dealer duo studied with her in Pennsylvania), and now an East Coast museum has acquired a major ship painting, with curatorial interest rising across the bar. In January, look out for a solo show of her work at CANADA.

DONA NELSON

Thomas Erben Gallery (New York)

A painter who graduated from the Whitney’s Independent Study Program in 1968, Dona Nelson has since then worked on creating performative, AbEx-style canvases that endeared her to her artist peers who could read the incredibly thoughtful process behind each one. She didn’t, however, enjoy the games of the market, refusing to entertain collectors or play to the social aspects of the art market, preferring to remain extremely indifferent to the commercial reception of her work.

In 2000, the painter Louise Fishman introduced her work to Cheim and Read gallery, which gave her a pair of shows over the next two years, but she was never completely comfortable with the gallery’s space or its business imperatives. Around that time she began making as two-sided canvases—meaning that they couldn’t be hung on a wall, but rather displayed on a space-consuming stand to be walked around, like a sculpture.

She and the gallery parted ways—neither felt is was the right match—and those double-sided paintings have now been embraced by curators for the way they form a meticulous duet of surfaces, with brushstroke on one side bleeding through to factor into the composition on the other. Nelson had two of these paintings in the last Whitney Biennial, and others were acquired from her last show at Thomas Erben Gallery by the Rose Art Museum, the MFA Boston, the Kadist Foundation, and the Art Gallery of New South Wales in Sydney.

Today she works out of her garage studio in Lansdale, Pennsylvania, and is represented by Thomas Erben Gallery. Erben, who also reps the 81-year-old British sensation Rose Wylie, seems to work well with Nelson, in part because he has put commercial necessities on the back burner—but not out of pure idealism. “Once the work becomes institutionally validated its historical importance will find its commensurate commercial value eventually,” he pointed out.

Dona nelson rear at Thomas