When it comes to art fairs, Misako and JeffreyRosen of Tokyo’s Misako & Rosen gallery face a different set of challenges than many of their peers. As young gallerists, they’re struggling to solidify the perpetually-burgeoning Japanese art scene while simultaneously fighting against an international ignorance of current Japanese aesthetics outside of stars like Takashi Murakami and Yoshitomo Nara.

Nevertheless, the dealers have been able to leverage their extensive experience in galleries like Taka Ishii and Tomio Koyama as well as the creative energy of their roster of Japanese and foreign artists to establish Misako & Rosen as one of the preeminent new galleries in Tokyo. They have also helped to create the New Tokyo Contemporaries, a loose network of youthful and like-minded exhibition spaces in the city; its purpose, as Rosen says, is to foster “the cultural context out of which a market develops.”

This emphasis on collaboration coupled with a strong distrust of the booming art economy makes Misako & Rosen something of an anomaly in our time of mega-galleries and massive sales. It’s not the prominence of art fairs they’re balking at (they’re longtime members of NADA, and proud participants in this year’s edition of Frieze London), but rather the speculative frenzy these settings encourage at the expense of a wider conversation on the relevance of the art itself (especially, they have found, in Asian countries). To find out more about their approach to running a commercial gallery according to these seemingly anachronistic principles, Artspace’sDylan Kerr spoke to Rosen about his reservations about the current art market bubble and why the exhibition space still matters.

How did you first get started with the gallery?

I’ll try to give you the short version of a very long story. Both Misako and I spent our youth working for first-generation contemporary Japanese galleries—I was with Taka Ishii, and Misako had been working for Tomio Koyama Gallery since she was 19. I moved to Tokyo in 2002 and met Misako at that time. We were a couple, but it wasn't until after we married that we opened the gallery, which was in December 2006. Both of us worked for those galleries for ten or more years before deciding it was time to open up our own space.

This decision was partially inspired by the first of the second-generation contemporary Japanese galleries, which was a space called Takefloor. Kazuyuki Takezaki, who we now represent as an artist, started this space in his apartment in the neighborhood of Ebisu. It was a tiny apartment, and it functioned as his studio space, living space, and exhibition space. It was analogous to something like Daniel Reich’s gallery in his apartment back in the day, and it gave everybody of our generation the courage to start opening up our own spaces. It seemed like an obvious thing to do at that point, because galleries of the first generation were older than 10 years, the emerging artists had become more established, and the context of those galleries’ programs didn’t necessarily make sense for the artists that we grew up with, many of whom were also working for galleries.

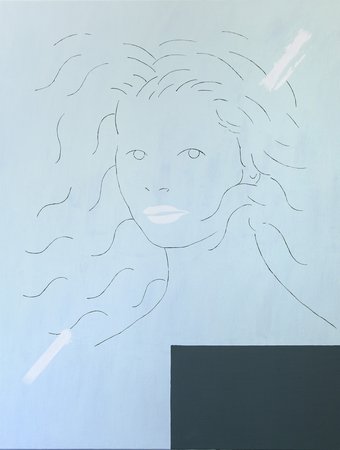

Kazuyuki Takezaki's 88, 2015

Kazuyuki Takezaki's 88, 2015

Do you consider yourself part of this second generation of Tokyo galleries?

Yes. Together with some of our friends—some of whom have closed their galleries, some of whom are driving now—we started an informal organization called New Tokyo Contemporaries. This was actually was sort of modeled after NADA. In Tokyo, where the model is cooperative rather than adversarial, it made sense to pool our energies and efforts together to try to build something from what still is sort of nothing, in terms of a market. It was easy, because we’re all friends and we’re used to working together through the first generation of galleries. This is, I have to say, very different from my experience working in the art world in the United States.

Can you say more about these differences between the American and Japanese art contexts? I’m especially interested in the collaborative versus competitive approach.

I don’t want to generalize too much about the way people do business in the United States, and of course something like NADA is a perfect example of the contrary, which is one reason why we’re so happy to have been involved in the organization for such a long time.

In Japan, when you’re dealing with a handful of collectors, there can be a temptation to try to keep them to yourself. What we did instead was to organize a series of events, more akin to festivals than art fairs. These were always curated exhibitions featuring artists from all of our galleries. It was a way to introduce our collectors to their galleries and vice versa, to try to generate enthusiasm for what was happening in the hopes that that would balloon into something beneficial to us all.

At the same time, I have to say that the older galleries were incredibly supportive of our efforts. In fact, I was still a full-time director at Taka Ishii Gallery until two years ago. Misako has run our space full-time since the beginning, but I was only able to join her in the fun a couple of years ago. Again, it was a situation that was really mutually beneficial. I might be asking to take time off from my job at Taka Ishii to travel on behalf of Misako & Rosen, but at the same time there might be an opportunity to do some work for the other gallery over the course of my travels. Since both galleries trusted that I was working in everybody’s best interests, I was actually able to accomplish quite a bit given my own inherent limitations [laughs]. It was a really great situation.

I don’t know other dealers who have been in the same situation of holding two jobs at the same time, but I know that all of the members of the New Tokyo Contemporaries were educated, in a manner of speaking, by the first generation of galleries. The galleries in the New Tokyo Contemporaries that are still open are by and large run by the people that were working for internationally active first-generation galleries like Ota Fine Arts or Mizuma Gallery.

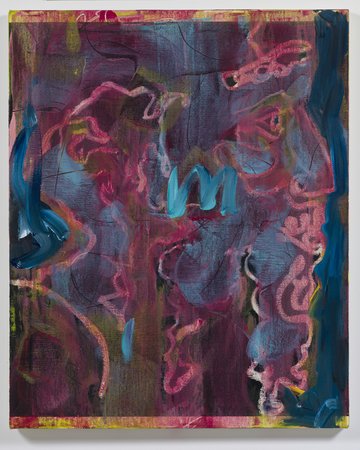

Kaoru Arima's Movie Theater, 2015

Kaoru Arima's Movie Theater, 2015

How do you think Tokyo-based artists deal with working outside of the established “art world capitals?”

We’re sort of in a perpetual situation in Japan that looks like what you might see after the art market collapses, when you have some years during which people throw caution to the wind because there’s no market pressure or worries. No one is pumping out work to sell it, of course, because there’s hardly anyone buying it. Artists are left alone to develop their practice.

I think it’s a very positive thing, because the work matures at an even pace. And although it takes a lot longer for people to recognize the work of a Japanese artist outside of Japan, when people think about quote-unquote Asia, and they think about where interesting art is being made, they’ll look to Japan because there’s very little market hype here outside of a few movements.

Young or emerging art here often means you’re in your mid-forties, because it takes that much time to develop a career outside or inside Japan. Even artists who have a strong career within Japan—and by that I mean a significant exhibition history within Japanese institutions—still are only being recognized in their forties, if then, outside of Japan.

A lot of this has to do with a lack of context, with people’s inability to read Japanese art. The downside to what happened in the 1990s, when the work of Murakami and Nara became so popular, is that it limited people’s ability to understand or view any other kind of Japanese contemporary art. It was just assumed that that was the dominant aesthetic, and while it was and continues to be very important, there’s just no context for understanding the other things that were happening here at that time.

Part of the strategy that was adopted by the first generation—which did have some benefits—is that you would see Japanese gallerists presenting the work of more historical Japanese artists together with younger Japanese artists in the only place where people would actually pay attention to that, which is the art fair. Good examples are Taka Ishii Gallery showing artists from Jikken Kobo [Experimental Workshop] from the ‘50s, and Tomio Koyama Gallery showing artists like Kishio Suga of Mono-ha. The plus side of this effort is that it helped people develop a way to read the work of some of the younger Japanese artists. The downside, perhaps, is that when something gains significant traction within the market, it can eclipse anything that complicates a simple reading. This is partially what’s happened over the past 15 years or so.

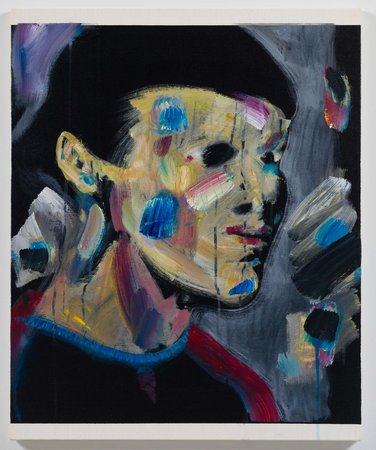

Shimon Minamikawa's Condition Check 12, 2015

Shimon Minamikawa's Condition Check 12, 2015

I’m glad you brought up the impact of art fairs. As a relatively young gallery, how do you approach a fair like Frieze? How do you make decisions about which artists to bring, how to lay out your booth, and which collectors to reach out to?

As a Japanese gallery, we have to think about things in a different way. The art fairs are the best places for us to generate the context for the work we’re showing in an international vocabulary. By presenting the work in that setting, it helps people to read it in other contexts as well, so our approach is very strategic.

For this year’s booth at Frieze London, we presented a digest of the three Japanese artists that we previously showed in Frieze New York’s Frame section over the past three years—Shimon Minamikawa, Kaoru Arima, and Kazuyuki Takezaki. Whereas in New York we showed them in solo presentations, in London showed them all together. Hopefully, this is all building upon itself on multiple levels—not just among the collectors, who have presumably visited both Frieze New York and Frieze London, but also in terms of the wider cultural conversation.

Why do you think those three artists are particularly well suited to the art fair context?

The market is very difficult to read, but you intuitively have a sense of what’s happening culturally. For instance, around the time we decided to show Shimon in New York, he was offered a solo show at 47 Canal. Ultimately, that led to our co-organization of a performance, which was presented in conjunction with the fair. It’s not something we had planned in advance, but the gallerist’s job or talent is not so much to follow what’s happening but read the direction in which the conversation is moving. In the case of Shimon, it ended up making perfect sense.

Kazuyuki Takezaki had just come off of some relatively major museum exposure in Japan. To make a long story short, Takezaki was asked to participate in a group show with friends that we made from a German gallery called Chert. This show was a way to widen the conversation around younger Japanese art, from a historical rather than Modernist perspective. It was a response to what was happening very specifically to us as well as to the wider cultural context.

Kaoru Arima was an artist we had just started working with when we first brought him to Frieze New York. He was sort of a hero in Japan in the 1990s—he presented his work in the Carnegie International, and he was collected by a number of institutions inside and outside of Japan. Unbeknownst to us, he was already a fan of our gallery’s painting program. He decided to create a body of painting in response to that—it was the first time he had really worked in that medium. His approach to painting is experimental and highly personal—it’s something that you might not think would work in a fair context, but the atmosphere and energy that Frieze provided in the Focus section was perfect for us to reintroduce an artist that people were familiar with while also allowing them to see a new side of his practice.

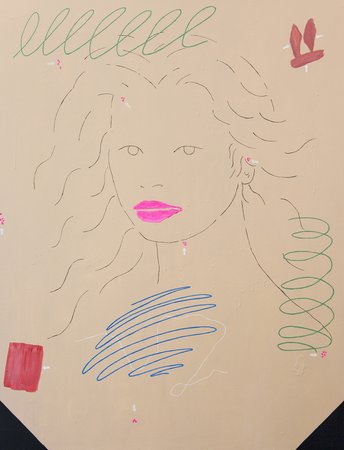

Kaoru Arima's Forever Outline, 2015

Kaoru Arima's Forever Outline, 2015

What about fairs that are closer to home, like Art Fair Tokyo?

It’s a little bit different for us. We’re not worrying about showing that we’re at Art Fair Tokyo and introducing the work to the market that way, because there’s no context for a fair to really work in Japan. The primary vehicle is the exhibition program. It may be old-fashioned, but it’s through the exhibition program that we’re really able to excite the people about the work and generate a context here at home. I believe this is of crucial importance, because we’re actually in a really horrible period. Things are booming commercially within Asia, and I think it’s awful.

I don’t know if I’ve ever heard a gallerist talk about the booming art economy in those terms.Why don’t you think art fairs work in Japan?

It sounds foolish, but let’s put it this way: for us, it doesn’t make sense that you would have an art fair before you have an art market, and it doesn’t make sense for you to have an art market before you’ve generated a cultural context out of which a market develops. It seems like what’s happening within Asia is completely backwards—you have value generated purely from the market.

Now, this could be something that we’d have cause to celebrate. If you’re cynical or opportunistic, then this must be the easiest situation to read. It’s not about the tricky business of culture, it’s about tricky business, period. This is so far away from what we’re interested in. We are a commercial gallery, and we’re happy when our artists and the gallery achieve greater and greater financial success, but I’d like to think that’s something you earn via cultural significance, not something that you generate from within a market.

We don’t participate in fairs within Asia at all, because it doesn't make sense to us. Why would we be doing that? You’d think there would first be some kind of cultural exchange between countries within Asia—you’d think we’d be doing partner exhibitions with some of our fellow gallerists in other Asian countries, you’d think there would be museum shows, artist-run spaces, all these conversations out of which a market develops. This is the healthy way to do things—this is what makes sense. Instead, you have this machine, this monster, that is so far removed from anything that we’re interested in.

The reason we’re continuing to participate in Frieze and NADA is that it seems like their priorities are in the right place—they have integrity. It’s not about how much money we can make and how quickly we can make it, not that the money isn’t important. Again, we’re a commercial gallery, and I’m proud of that. But Asia, from within, seems like a nightmare version of the international market. It’s concentrated. Auctions generate value outside of any cultural significance.

Shimon Minamikawa's Condition Check 13, 2015

Shimon Minamikawa's Condition Check 13, 2015

What piece of advice would you give an aspiring gallerist, perhaps as an antidote to some of the issues you just raised?

I would suggest working for a gallery whose program you admire and learning as much as you can from them before opening your own gallery. It’s relatively straightforward [laughs].

It’s an optimistic time here in Japan because we have a third generation developing—we’ve been through our ten years and we’re seeing young galleries opening. There’s been a bump in the road because there were some people in between who tried to open their own spaces but who didn’t have an education. By education, I don't mean going to university for art history or anything like that—I mean having an apprenticeship at a gallery. I worked for Taka for 15 years before we opened this space, and I feel like that was time very well spent. I think part of the reason we can stick to our guns and have some success is that we know what we’re doing because we studied by working with gallerists we respected. I think people get caught up in the hype and think it’s just a fun thing to do. It is fun, of course, but it doesn’t make sense if you don’t know what you’re doing.