Lauren Luloff makes paintings with bleach and muslin, combining layers of fabric with delicate prints and floral motifs to make collaged compositions that seem barely moored to the stretcher bars that frame them. Her gauzy creations have becomeperennialfavorites of top-tier collectors like Susan and Michael Hort, and she’s been at the center of well-received solo shows at galleries including Halsey McKay, Cooper Cole, and Marlborough Chelsea. Here, Artspace’s Dylan Kerr talks to the young artist about her formative years and unusual approach to art making.

What are some of your early influences?

I had an amazing teacher when I was a freshman in high school whom I worked with after school once a week. It was an open studio setting in a space where Amalia, the teacher, also worked making art, used the back half as her own studio but also working alongside us, easily introducing us to abstraction by her example. I was the oldest one in the class—the other few students were four or five years old, and I remember them playing with clay and sometimes crying.

I would have ideas of things I wanted to try, and Amalia would help me actualize my visions. I wanted to make thick, lumpy paintings, so she showed me how to mix rocks and dirt into my paint. She always let me choose my path and offered resources to continue my explorations. The possibilities felt endless, and sculpture was easily incorporated into painting.

Can you describe a pivotal moment in the development of your work?

The most influential experience I've had recently was traveling to India and working with an amazing textile artist named Irfan Khatri to learn the ancient technique of block printing. The way the repetitious mark is infused in the fabric was a complete mystery to me. I was bewildered by both the completely handmade quality of all aspects of the craft—hand-stamped fabrics, hand-made wooden blocks, natural vegetable dyes—as well as the simple technology of the stamping itself. The technique is thousands of years old, and it takes days to complete the fabric. It depends on the particular arid climate in Gujarat to bake in the colors.

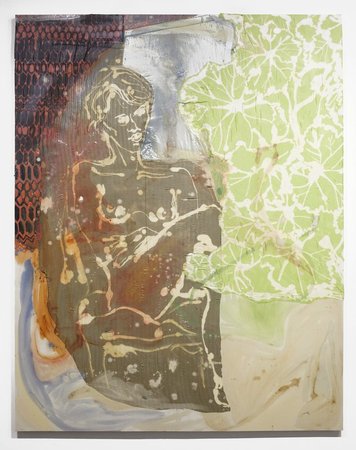

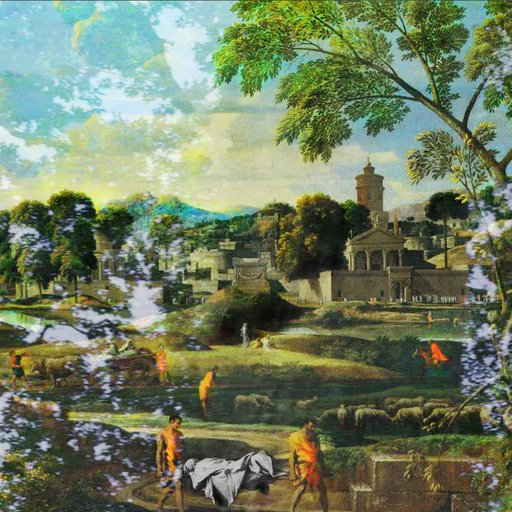

Exposure to this craft completely transformed my work. I started to work with bleach to mimic the gradations and tones in the printed fabrics, and I became absorbed in studying the complex patterns and incorporating them into my language of drawing. Prior to this series, I also worked with bedsheets, many with printed patterns that I would incorporate into my paintings somehow, but this shift to bleaching or burning in my own handmade efforts at Gujarati-inspired prints was a huge shift for me. This exploration eventually opened up over the past few years—I've drawn plants, still lives, landscapes, and figures using the same bleach technique while still incorporating the Gujarati prints I love.

What do people not get or usually miss when it comes to your work?

A lot of people are surprised when I tell them all the marks—patterns, people, et cetera—are hand painted with bleach. I wonder where they think I get the fabrics from!

Jenn in Garden, 2014

Jenn in Garden, 2014

Who are some contemporary artists you follow or are friends with?

The artists whose work means the most to me are the artists I’ve had the privilege to be close to—the ones I've shared both studio space and my life with in major ways. My husband, Alexander Nolan, is such a creative genius, and I get to see his world unfurl everyday since he works from home. We've also done residencies together where we've worked side by side for weeks, sharing meals and swims and creative effort.

Tisch Abelow was my room- and studio-mate for years, and her feedback and influence has been incredible. We are such different artists but prize that difference dearly and have had so much to offer each other because of it. Jane Corrigan recently had her studio on my floor and we became very close, too, diving into each other's work and minds. This is when the artwork means to most to me—when I love it, it moves me, but I also love the person and am so honored to witness their artistic evolutions, struggles, and epiphanies.

What book or books do you consider required reading when it comes to approaching your work?

I don't think any reading is required to understand my work. I think my work comes from a non-verbal place, and I prize that place. I think it depends more on a person's relationship to their memory and sensory experience, since so much of my focus is on colors, surges, and images that come in and out of focus.

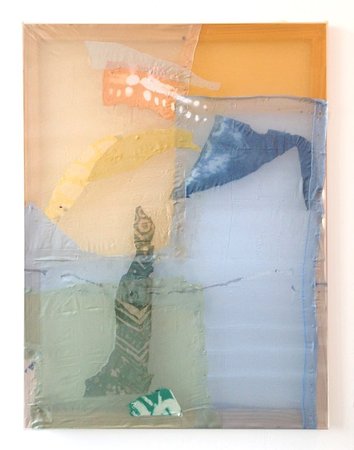

Your recent works often highlight the armature of the canvas itself through your use of sheer fabrics that show the stretcher bars behind them. Why foreground these usually hidden aspects of a work’s construction?

It's funny—initially, I never really thought about showing the stretcher bar as an intentional move. I first made these sheer paintings free-hanging, and they were nice like that—shifting in space, you would see images from different paintings through the transparency of others and this euphoric, dreamy collection of images emerged.

It was actually Kathy Grayson from the Hole who suggested that I try to stretch them and see what they looked like. I was struck by the oddness of these loose, limp images suddenly on sturdy, handsome frames. I’ve been working that way ever since—I like the geometric structure beneath my oozing curtains. I also starting having beautiful frames made for me by professional woodworkers, based on the rugged frames I had made for myself since college. The new frames are so elegant, and I love the way they complete the loose structure and pull everything taught.

What’s the balance between painting and construction in your works? Do you think of the various materials you use as part of your painting toolkit, or are these works functioning more like collages or assemblages?

The different aspects—paint and construction—happen at different times and in very different ways. I usually go on a painting spree for a couple months, accumulating a mass of bleach drawings to work with. I spend months drawing trees outdoors, drawing friends and my husband or plants and objects and, of course, drawing patterns in my studio. Once I have a big collection of bleach drawings I cover my walls with them and start to find combinations and create compositions. This part of the process also takes several months. Sometimes I have to stare at a particular arrangement for weeks before it seems solid enough to fix, or until I realize it's not falling into place. Once I get a combination of elements that really resound in me, I glue them together. I don't sew because it seems too tedious, and I like the painterly quality of using glue.

As a counterpoint to my previous questions, it seems like many observers of your work (myself included) tend to focus more on your use of novel materials than the painted work itself, which ranges from female nudes and floral motifs to more abstract gestures and patterns. What do we need to know about you as a painter?

That's a good question—it seems my material exploration has often obscured the underlying subject matter. In a way that's sort of nice, because my stories remain secret and unobserved to many people. It's difficult for me to know how to respond to the issue, since for me the narratives are so clear despite being wordless and abstract and I do meet people who can read the work in very sensitive ways. The viewers’ response is such a reflection of themselves, and I've always cherished the inherent disparity in how any two people see a work of art.